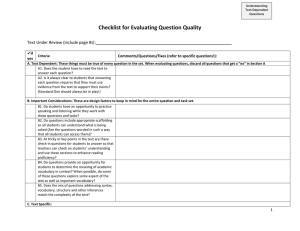

supporting students in close reading

advertisement