Davida Malo, Nathaniel Emerson, and the “Sins” of Hawaiians: An

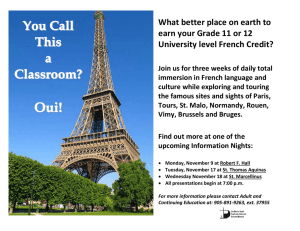

advertisement