Shabbat Announcements - Mount Freedom Jewish Center

advertisement

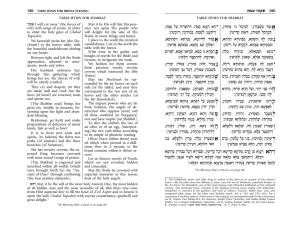

Shabbat Announcements December 6, 2014 14 Kislev, 5775 Shabbat Candle Lighting: 4:12PM Friday Night Mincha: 4:10 PM Morning Services: 9:00 AM Shabbat Mincha – After Kiddush Shabbat Ends: 5:13 PM Vayishlach Page 170 (Torah) Page 1141 (Haftarah) Find out more: Shabbat Morning Partnership Minyanim – This Winter! We extend our deepest sympathies to Jill Saxon and her family on the passing of her beloved grandfather, Mr. Stanley Beck. This Week: December Birthdays & Anniversaries December Birthdays: : Irene Billinson ( 1st), Alanna st st Dawn Bravman (1 ), Sarah Lily Stein (1 ), Howard nd nd Krosser (2 ), Jessica Scheer (2 ), Adam Goldblatt th th th (5 ), Gabriel Korish (6 ), Helen Schwartz (6 ), Elisa th th Sara Schwartz (8 ), Miriam Czeisler (10 ), Jordan th th Rubenstein (11 ), Allison Lieberman (12 ), Richard th th Zwickel (12 ), Doris Brooks (13 ), Rebekah Shalit th th (14 ), Michael Chevinsky (15 ), Shoshana Beacken th th (16 ), Alexandra Kass (16 ), Melanie Weinstein th th th (16 ), Bruce Goldman (17 ), Rachel Inger (17 ), th th Edden Chirnomas (19 ), Daniel Hakakian (20 ), rd rd Jacob Billinson (23 ), Michael Okun (23 ), Gary rd th Scheer (23 ), Marsha Hoch (25 ), Ziva Lily Gutkin th th (26 ), Akiva Cahn-Lipman (28 ), Annette Eichen th th th (29 ), Dori Rachel Gelb (29 ), Alan Gellerstein (29 ), th th Steven Stein (29 ), Lillie Brandt (30 ) Max Ezra th (30 ). December Anniversaries: : Louis & Madeleine st nd Pasteelnick (1 ), Murray & Jaine Karten (2 ), th Howard & Roz Krosser (14 ), Lou & Linda Koval th th (18 ), Marvin & Miriam Raber (18 ), Mark & Martha nd th Moritz (22 ), Ira & Paula Antin (25 ), Gary & Susan th Scheer (25 ). MFJC INFO ~ www.mtfjc.org Address: 1209 Sussex Tpk., Randolph 07869 Phone Numbers: Office: 973 895 2100 Rabbi: 973 895 2103; Rabbi’s Cell: 201 923 1107 Rabbi’s Office Hours: Mornings: Tues - Fri, 9-1PM; afternoons/evenings: 3-6PM; or anytime by appt Menashe East rabbi@mtfjc.org Office Hours: M-Th, 10- 5PM; F, 9-4:30PM David Paris office@mtfjc.org Dec 6: Welcome Reb Daniel – Rabbinic Intern Dec 6: Shabbat Youth Activity – Parsha with Reb Dan, 1045AM; Rishonim Shabbat Program, 11AM Dec 6: Torah Talk with Reb Dan, Baum Hall, after Mincha…Women Dec 7: Talmud Study, 9AM Dec 7: UJC Super Sunday – answer the call! Dec 11: Mishlei Seminar, 10AM Dec 11: I-Torah, Vayeshev, 830PM Upcoming Events: Dec 13: Uriah London’s Ufruf Dec 13: Kids Movie Night, 6PM, See Flyer Dec 16-24: Chanukkah!!! Dec 16: Kids Chanukkah Party, 500PM. All Hebrew School and Shul Children are invited! Dec 16: Communal Menorah Lighting on MFJC’s Lawn, 6PM Dec 19: Partnership Minyan Dinner, RSVP to Evite Dec 20: December Shared Kiddush/Chanukah Kiddush – Please contact the office to be a sponsor for your family’s Simchas Jan 1: Fast of the 10th of Tevet and Gregorian New Years – Morning Services, 8AM; Mincha, 415PM; Fast Ends, 525PM March 7: MFJC Purim Shpiel & Dinner MFJC SERVICE TIMES: Weekday – 6:45AM Weeknight – Upon Request (Yahrzeit) Sunday & National Holidays – 8:00AM Shabbat Services – 9:00AM How To Connect With Us Mt. Freedom Jewish Center - on the Web! www.MTFJC.org - YES we have a NEW LIVE website!!! Please visit and give us feedback as we are still adding new features and content! Facebook Please “Like” our page Mt. Freedom Jewish Center Not on Facebook? Visit www.facebook.com to enter your email and create an account! Instagram Follow us, tag us, like us! Mtfreedomjewishcenter Not on Instagram? Download the app for iphone or android and get started and enter your email address or link your facebook to get started! Twitter Chat with us on the twitterverse! @Mtfreedomjc To join download the Twitter app for your smartphone or visit www.twitter.com to get started! Having Trouble? Please email Gabrielle.r.auerbach@gmail.com for help getting connected. Chesed Call to Action Our Chesed Committees have taken off running, offering us a steep learning curve in the process. Thanks to all of you who have made such a difference for our families in need. Going forward, we will use the Shabbat Bulletin as a way of communicating changes and improvements to our process. Every few weeks, or as needed, we’ll offer news and describe new developments, all with the aim of improving our effectiveness. So please watch this space. New Developments For every new situation, whether it connects to our Homebound or Shiva committees, the person or family in need will be asked to specify a friend or family member, inside or outside the community, to serve as a Chaver or Chavera. It will be the responsibility of these Chaverim to serve as point people, directing the energy of our committee members and congregation to best serve the person or family in need of support. Marsha, Ellen, and the Rabbi will work to be sure our Chaverim have the tools they need to get the job done, including phone numbers, email addresses, and to-do lists (in the case of preparing a shiva home, for example). Going forward, we will organize all meal deliveries through the Take Them a Meal website. It is so easy to use that it takes all of a moment to set up. Our password will always be Mount Freedom; the page will be tagged with the last name of the person or family in need. It will be the job of our Chaverim to send the link for the page to the committee involved, as well as to any shul or community members who would like to be included. Again, Marsha and Ellen will make sure Chaverim have instructions for setting up the page, as well as committee email lists. Action Step: Items Needed by the Shiva Committee In a shiva house, mirrors used by the mourners are customarily covered. Rather than scramble to find sheets each time the need arises, we will assemble shiva supplies at shul and have them ready to go. Please, if you have clean, solid flat sheets that you can spare, leave them at the shul. We will have a collection box next to Lew’s Community Food Bank box. If you would like to donate rolls of masking tape or plastic tub containers for storing the sheets, please leave them in the same place. We need only 8 or so sheets, and perhaps two medium-large containers. We would also like a small suitcase on wheels for transporting siddurim if anyone has one to donate. Up Next Look here in the weeks ahead for a brush-up on what help our committees can provide and the process you should follow if you need support. Mt. Freedom Jewish Center’s Chanukah Youth Fun Night ~1st Night of Chanukah~ December 16th ~ 5-6:30 (Don’t worry, you’ll be home with plenty of time to light Chanukah Candles!) Crafts Games & Prizes Chanukah Sing Along Oily Donuts & Greasy Latkes Special Giant Outdoor Menorah Lighting Admission: $5 per child + 1 Toy for donation Contact Lisa Gutkin or the Shul Office to RSVP lisatgutkin@gmail.com or Office@mtfjc.org . Instructions on how to win the lottery At the start of this week’s Parshah Jacob is concerned about an upcoming reunion with his brother Esav who wanted to murder him the last time they met. The Ramban (Nachmanides) states this Parshah gives us the template for Political Science or State craft. We should make diplomatic attempts (Jacob sends gifts), we should prepare our camp for war (Jacob splits his camp in two) and we should pray (Jacob exhorts G-D for help). I try and keep this sage advice in mind during these trying times in Israel. Why does Jacob have to do all this preparation if G-D can help him? Doesn’t this show a lack of faith that his prayer will be answered? “G-D helps those who help themselves”- Benjamin Franklin “ You can’t rely on G-D for anything, he practically told me so himself”- Bender Success in this world is like sailing. If we put up our sails, (representing our personal effort in this world) and there is no wind (representing Divine assistance) we will not move. No matter what we do G-D must assist us or our efforts will not get off the ground. However if we do not put up our sails, no matter how much wind we get the boat will only move slightly because we have not created a vessel, or receptacle to harness G-D's blessing. Sometimes we must become an atheist in Gods name . When we witness suffering or injustice it is cruel to say this is God's will, we must stand up and protest. Faith in G-D is not a big deal She is all powerful. Faith in yourself, that is something amazing. In order to win the lottery you have to buy a ticket. Shabbat Shalom Reb Daniel Epstein WEEKLY PARSHA By Rabbi Dov Linzer, Rosh HaYeshiva and Dean of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Parshat Vayishlach | December 5, 2014 / 14 Kislev 5775 VaYishlakh – My Name is Yaakov “And Yaakov was left alone; and there wrestled a man with him until the breaking of the day” (Breishit, 32:24). Who was this man? The most common explanation is that it was an angel, the “Heavenly prince of Esav,” and that this wrestling represented Yaakov’s struggle against his external adversaries and anticipated the momentous encounter he would soon have with the earthly Esav. It is possible to suggest another interpretation. While Yaakov had to struggle against many outside forces throughout his life, perhaps his greatest struggle was internal. Even for those inclined to have an idealized view of the Avot, the character of Yaakov presents major challenges. He takes advantage of Esav at a moment of weakness to buy the birthright, and he misrepresents himself to his father to take the blessing intended for Esav. He even seems to bargain with God: “If God is with me… and gives me bread to eat and clothes to wear… then this stone… shall be a house of God” (28:20–21). And in his dealings with Lavan, Yaakov seems to be using every scheme and loophole to maximize his profit. In short, what we have seen up until now is that Yaakov has lived up to his name: “This is why he is called Yaakov, for he has schemed against me these two times” (27:36). Yaakov’s greatest challenge, then, is not what is outside of him, but what is inside. He has to grapple with those qualities in himself that lead him to taking the easy way around things, to avoiding conflict and scheming to get his way rather than to tackling his problems head-on, with honesty and integrity. This internal struggle and the resulting transformation have, in fact, already begun. By the end of his stay with Lavan, we hear that his shepherding was done with great self-sacrifice. As he tells Lavan with full confidence: “That which was torn of beasts I brought not unto you; I bore the loss of it… In the day the drought consumed me, and the frost by night; and my sleep departed from mine eyes” (31:38–40). This is a model of honesty, integrity, and work ethic that most of us could only hope to live up to. Yaakov was thus a paragon of virtue in matters of money (itself no small feat), and perhaps he only employed his devices with the sheep to counteract Lavan’s double-dealing. But how will he react when he encounters Esav, when what is at stake is not just money but relating to Esav and owning up to his misdeeds of the past? It would be very tempting for Yaakov at this moment to convince himself that he acted correctly those many years ago, to continue thinking positively about himself, and to continue feeling entitled to his father’s blessing. Just consider how often we engage in similar self-deception, digging in our heels to convince ourselves that we are in the right so that we don’t have to confront our own past shortcomings and sins. It is at this critical juncture that Yaakov is left alone, not just physically but existentially, alone with his own thoughts, his own character, and his own complex personality. He must grapple with the different parts within himself, his tendency to scheme and his desire for integrity and honesty. Will he be the same Yaakov, will he continue to deceive not just others but even himself? Or is he able to embrace the harshest honesty – honesty with oneself? Significantly, at this moment of struggle Yaakov is asked – or he asks himself – who he is: “And he said to him, What is your name?” In sharp contrast to the past, he does not claim to be Esav; he does not engage in deceit, lying to himself about who he is. Instead, he answers simply and honestly: “And he said, Yaakov.” He is able to come to terms with those less-than-ideal parts of himself, the Yaakov/ekev/deceiver within. By not denying this part of himself, by accepting it and being prepared to deal with it, he is ironically now able to become someone else: “No longer will Yaakov be your name, but Israel.” The Rabbis tell us that Yaakov went back to retrieve the pachim ketanim, the small vessels that he had left behind. These represent the small vessels that are within us, those easily ignored unpleasant pieces that are a part of us. When we want to move forward in life, it is easier to gloss over our small shortcomings. Paying attention to those will just hold us back, we say to ourselves. But we ignore them at our own peril. As the saying goes: Wherever you go, there you are. We can never escape who we are, and if we try to ignore those problematic personality traits, they will undoubtedly resurface, probably at the worst times, at times when we are under the greatest pressure. Yaakov’s greatness was his realization that in order to go forward, he first had to go back. He had to confront himself and struggle with himself, owning who he was and what his shortcomings – his pachim ketanim – were so that he could then grow and truly change. Yaakov was victorious in his struggle in the end, but it was not a victory in the simple sense of the word. He did not destroy those vessels; he did not eradicate those parts of his personality. How could he? They were part of him. Rather – “you fought… and you were able” – he found a way to control this part of himself. He became able to dictate how these character traits would be expressed rather than letting them dictate his actions. This is the name of Yisrael, not that you conquered or destroyed your demons but sarita – from the word sar, to be a master – that you have gained mastery over them. He is now someone new, a Yisrael. And yet, as the later verses make clear, he remains a Yaakov. He is a Yaakov who now knows who he is and thus a Yaakov who has mastery, a Yaakov who is a Yisrael. We all have our shortcomings. No matter how far we have come, if we do not engage in this Yaakovian selfgrappling, if we do not go back for those pachim ketanim, we risk having these blow up on us at a later time. This, in the end, is the goal of therapy: to learn to recognize those undesirable parts of oneself, to be able to predict when they may be triggered, to moderate these traits, and most importantly, to choose to act differently. The goal is integration, not eradication. It is true that there are some vessels that we should not go back for. Some things about us may never change, and we need to learn to make peace with those parts of ourselves. To quote the serenity prayer of Alcoholics Anonymous: “God, give me grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, Courage to change the things which should be changed, and the Wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.” Yaakov’s greatness was first recognizing that the vessels were there. But his second greatness was knowing that this was something that he could deal with and he could change. Most of us, I imagine, too readily put things in the “cannot be changed” category and give ourselves a pass on doing the work that needs to be done within. Recognizing those things that can be changed, going back for those pachim ketanim, however, can be truly transformative. Yaakov’s struggle was a heroic one, one that is crucial but that we often shirk from undertaking. It can be painful and make us feel vulnerable. Perhaps we are afraid that we, like Yaakov, will emerge from it limping, wounded, and weaker than when we started. This may indeed be a stage in the process, but it is necessary so that we, also like Yaakov, can emerge whole, can be a complete self: “And Yaakov arrived complete to the city of Shechem.” (33:18). For religious leaders, to engage in such a process is all the more necessary. The demand to see oneself as a representative of the mesorah and a model of ethical probity often makes it hard for a religious leader to be honest about his or her own shortcomings. But such self-deception is a recipe for disaster. Such leaders risk either convincing themselves of their own infallibility or, conversely, allowing the “guilty” knowledge that they have these less-than-ideal personality traits to eat away at them until these traits seek a form of release, often in ways that are both destructive to oneself and destructive to others. Both for their own health and for the religious and spiritual health of the community, it is necessary that our religious leaders engage in the struggle of Yaakov. We will only have true leaders of Klal Yisrael, leaders entitled to the name Yisrael, when they are also able to struggle honestly with themselves and say: “My name is Yaakov.” Shabbat Shalom Vayishlach 5775 (Genesis 32:4 – 36:43) Efrat, Israel - The biblical kashrut laws for Jews have always been a powerful tool in keeping us a “nation set apart.” We left Jacob last week leaving Laban and Laban-land behind, heaven-bent on returning to the land of Abraham and to the house of Isaac. Jacob understands that his inner self has been overtaken by the deceitful and aggressive hands of Esau, that he must return to his ancestral home in order to recapture the Abrahamic birthright. But what exactly are the building blocks of this birthright? Is it possible that Esau is now even more deserving, or at least as deserving of it as is Jacob? What is the real content – and significance – of our Jewish birthright? The very first prerequisite for the carrier of the birthright is a very strong Hebrew identity, a powerful familial connection which contributes – and defines – the link to a specific and unique heritage and ancestry. Abraham established his commitment to the Hebrew identity when he insisted upon purchasing a separate gravesite for his wife Sarah, when he was willing to spend a small fortune in establishing a Hebrew cemetery beyond the various sites of the Hittites. He defines himself as an alien resident, sees himself as living amongst the Hittites but certainly not as being existentially a Hittite, and therefore refuses an “of right” burial for Sarah in any Hittite plot of land (Gen. 23:3-20). Esau certainly is biblically described as having a strong sense of familial identity. He demonstrates strong feelings of filial respect and devotion; the Bible even records that Isaac loved Esau because he made certain to provide his father with the venison he dearly loved (Gen. 25:28). He even has strong sibling ties to his brother, despite Jacob’s underhanded deception surrounding the blessings. In the Torah portion this week, the Bible tells us how Esau first seemed to have set up a greeting brigade of 400 potential warriors to “welcome” the return of the prodigal brother (32:7); but once Esau actually sees his younger brother and his family, his heart apparently melts with brotherly love: “Esau ran to meet him; he hugged him, fell upon his neck and kissed him.” (33:4). Esau even wishes for the two of them to travel together and to settle down together. “Let us travel together and move on; I will go alongside of you” (33:12). It is Jacob who politely refuses: “You know that my children are weak and I have responsibility for the nursing sheep and cattle Please go ahead of me I shall eventually come to you in Seir” (33:13-14). Yes, Esau has strong familial identity. However, Abraham had two other crucial characteristics which Esau lacks: continuity and destiny. Continuity is most meaningfully expressed in marrying a suitable mate: from our modern perspective, taking a Jewish spouse (so that the children will remain Jewish), and from the biblical perspective, not marrying an immoral Canaanite. Esau takes Hittite wives (26:34), “Judith the daughter of Beeri and Basemath the daughter of Elon.” Perhaps he comforted himself with the fact that his first wife had a Jewish name (Judith) and the second had a name which means sweet-smelling perfume. Esau’s mentality is apparently as superficial as the name “Edom” he acquired from his exterior red complexion as well as the red colors of the lentil soup he exchanged for his birthright and the venison he gave his father. Moreover, when he realizes how upset his parents are with his marital choice, he still doesn’t look to his mother’s family in Aram Naharayim for a mate, but rather chooses a daughter of Ishmael, the “wild ass of a man whose hand is over everything.” And he takes this wife not instead of but in addition to his Hittite wives (28:9). Another test for continuity is a unique daily lifestyle, the ability to delay gratification and act with discipline, especially in the sexual and gustatory realms. The biblical kashrut laws for Jews have always been a powerful tool in keeping us a “nation set apart” which didn’t fall prey to assimilation. Esau sells his birthright for a portion of lentil soup – a thick, juicy filet mignon steak in our contemporary language. He even expresses his desire to have the broth “poured into his mouth” as one would feed a camel (25:30, see B.T. Shabbat, P.155 b, Rashi ad loc). To have one’s eyes on a historic mission, to realize the goal of having “all the families of the earth blessed by us” (Gen. 12:3) through our vision of a God of compassionate justice, morality and peace (Gen. 18:19), requires a lifestyle of commitment to an ideal and delayed gratification which is foreign to – and even impossible for – the character displayed by Esau. When Jacob tells Esau that he will meet up with him in Seir, our Midrash connects this rapprochement to the messianic period when “the saviors will go up to Mount Zion to judge the mountain of Esau” (Gen. 33:14, Obadiah 1:21, Bereshit Raba 78, 14). Jacob then continues to travel to Succoth, which implies the tabernacle and the Holy Temple, the place in Jerusalem from where our message to the world will eventually emanate (Isaiah 2, Micah 4). But before Jacob can affirm his covenantal continuity and begin to achieve his destiny, he must first disgorge the grasping hands of Esau which have overtaken his personality and substituted the Jacob (Yaakov) of “he shall emerge triumphant at the end” with “heel-sneak”; he must restore his “image of God” which was the source of that “wholehearted individual who was a studious dweller in tents.” This is the purpose of that mysteriously eerie nocturnal struggle with an anonymous assailant, a wrestling match which must precede the Esau-Jacob face-to-face confrontation. Jacob is all alone (32:25); his struggle is an inner battle, to rid himself of the heelsneak Esau in his soul. And he wins, both over divine forces and human powers (32:29); he has seen God (Elohim) face-toface, and succeeded in restoring his own divine image by exorcising Esau the heel-sneak. He now proudly stands Israel, the righteous representative of God and the fitting recipient of the Abrahamic birthright. Shabbat Shalom WWJD – What Would Jacob Do? This week is another climactic Torah reading. Vayishlach recounts the confrontation between Jacob and his angry older brother, Esav. Jacob expects the worst when seeing his brother for the first time in twenty years. His fears are heightened when his messengers return with the news that Esav approaches Jacob’s camp with 400 armed men. As Jacob prepares for, what looks to be, a bloody conflict, he faces the mysterious ‘man,’ with whom he wrestles and overcomes, though not unscathed. Jacob’s fears were misplaced; in the end, Esav and he embrace and part ways amicably enough. Jacob and his family move on to the next chapter in their life. They settle near Shechem. There, the text says, Jacob came to Shechem whole. The rabbinic interpretation of ‘whole’ is that Jacob’s Torah was whole; he was whole of body, and whole of spirit. This is a surprising explanation of a strange word. After all, Jacob was injured by the angel. Jacob was thinner in the pocket; he sent many extravagant gifts to Esav as bribes to curry favor with his enraged brother. And, Jacob had lived with Lavan these last 20 years, surviving the wily trickery that his father-in-law embodied. It is conceivable, if not likely, that he was somewhat deficient in his Torah. Yet the rabbis interpret Jacob’s life to be whole and perfect. It is the follow up to this verse that strikes us and makes a demand of us. Jacob comes to Shechem and he is whole and, then the text continues: ‘and he encamped – Vayichan – at the face of the city.’ (Gen 33:18) The word encamp is taken to mean graced. Jacob was Vayichan; he encamped or gave khen, grace to Shechem. How did he grace the city? The Talmud offers a number of suggestions. He developed a coinage system; he built bathhouses; he built marketplaces. (See TB Shabbat 33a) As an expression of thanks to God for helping him survive, whole and intact, after his encounter with Esav, Jacob helped institute community advancing measures. [Or, this can be viewed as Jacob’s expression of gratitude to the city of Shechem for hosting his family. (see Torah Temimah)] Jacob feels compelled to give grace and share his goodness because he feels that he is blessed and gifted with goodness. In this sense, we might be similarly motivated to perform acts of Chesed and to help our society and our world. We, the international Jewish community, the American Jewish community and the local Jewish community, have been gifted – some would say miraculously so – with bounty and security and a state. We have been through much travail and, yet, we are whole. And like Jacob, our posture – in answer to our feelings of wholeness – must be khen – to give our grace, to give gracefully. The book of Genesis is often thought of as a guide book; lessons from ages past unto this day. While the historic events became part of our historic legacy, the ethical and character traits are our spiritual heritage and we carry those every day. Shabbat Shalom Umevorach, Rabbi Menashe East