reasonable royalty for patent infringement of non

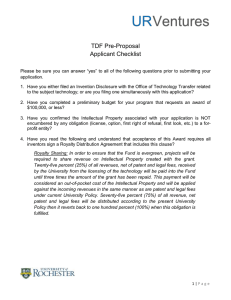

advertisement