Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) and Trade Facilitation: Best

advertisement

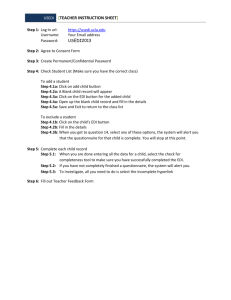

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) and Trade Facilitation: Best Practice and Lessons from Experience Benita Cox and Sherine Ghoneim The Management School Imperial College for Science, Technology and Medicine INTRODUCTION The increasing competitive pressures from both global and domestic markets are forcing nations to adopt new trade practices and standards. Nations need to adjust to new methods of trade information exchange, open up their telecommunications systems and learn to take full advantage of harmonized procedures, standards, and practices for trade documentation. The role of electronic commerce and electronic data interchange (EDI) in particular, is rapidly evolving in the face of increasing pressure from global markets to provide standardized methods and practices for international trade. The general term for these changes in international trade administration is “trade facilitation”. A World Bank study conducted in 1995 endorsed the use of EDI and electronic commerce as critical components of a trade facilitation strategy (Schware and Kimberley, 1995). EDI AND CHANGING TRADE REQUIREMENTS With the gradual removal of international trade barriers and the increasing interdependence between international organizations and markets, electronic data interchange (EDI) is expected to play a significant role in facilitating international trade (Farhoomand & Pace, 1995). EDI is the most prevalent form of electronic commerce supporting trade transactions across various industry sectors on a national and international level. EDI, as a system of exchanging standardized trade related information, is not only a fundamental IT business process reengineering tool (Benjamin et al, 1990; Fowler et al, 1994; Swatman, 1994; Swatman et al, 1994; Venkatramann, 1991), but also a key electronic commerce technique for the 1 reengineered trade facilitation process (Schware and Kimberley, 1995), especially with respect to customs and excise applications. Experts forecast a million users of EDI by the end of the year 2000. Recent statistics suggest that EDI users (excluding financial EDI users) are estimated to be in the region 170,000 users, seventy percent of whom are in the United States and Europe (Kimberley, 1998). At the national level the simplifying and speeding up of trade information flows offer significant national benefits. Singapore claims that properly applied trade facilitation is already saving it in excess of one percent of its gross domestic product (US$ 700 million in 1994) each year. As a result, reengineered trade processes based upon trade facilitation principles and EDI have become a global phenomenon (Schware and Kimberley, 1995). Therefore, an increasing number of nations are in the process of developing their EDI industry and there is an increasing requirement for the development of national frameworks and implementation guidelines. Developing nations, therefore, find themselves in the position of having to rapidly adapt their traditional trading practices in order to participate in international free trade. For many of these countries the barriers to achieving this are different and more complex than in more developed nations. Although Western countries have expended much energy in recent years defining international trade standards and founding the EDI and electronic commerce infrastructure, for developing nations, barriers to developing their national EDI industries and electronic trading communities are more complex than in developed countries. At the early stages of this research, the authors were particularly interested in applying a national EDI implementation framework to Egypt. Policymakers were particularly keen to develop the national electronic trading and information exchange infrastructure to serve the trading requirements of the domestic market. As such there was a requirement for identifying an EDI implementation model to address Egypt’s specific requirements. Research showed that in-spite of the large number of initiatives undertaken both at a national and international levels aimed at trade facilitation there remains a paucity in defining the factors critical to successful EDI implementation in a national setting. Furthermore, there was no single EDI adoption framework that addressed the complexity of developing a national EDI strategy. It has been acknowledged that there are a number of lessons to learn from Western mature EDI markets, yet it should be noted that these models are not necessarily appropriate for developing countries. For example, the literature suggests EDI success in the UK was primarily driven by the retail and manufacturing industry requirements and founded on the 2 advanced state of EDI service provision and telecommunications de-regulation. Egypt did not only lack the required EDI industry service provision and electronic commerce infrastructure, but also the powerful inter-organizational relations enjoyed by industries such as retail and manufacturing. As such it was necessary to examine the extent of EDI global presence and define the factors critical to successful EDI adoption in a national setting. At this stage it was also realized that the analysis should not be confined to infrastructural requirements, but should be extended to incorporate the nation-specific ‘contextual’ and ‘know-how’ requirements. EDI RESEARCH PERSPECTIVES Given EDI’s efficiency and strategic benefits, there has been a great deal of academic research into its impact on business operations and competitiveness. To date, existing EDI literature and research focused on a number of perspectives, each of which is typically addressed independently of the others. The first perspective considers the impact of EDI on inter-organizational structures (Cash & Konsynski, 1985; Benjamin et al.,1990). It considers EDI’s ability to facilitate the restructuring of industry as a whole as well as its ability to transform individual partnerships, for example, EDI’s potential to transform relationships between trading partners by bringing them closer (Johnston & Carrico,1988; Holland et al, 1992). The second perspective focuses on the role of EDI in business process re-engineering, its role as an enabling mechanism and vehicle for business process re-design and business scope redefinition (Benjamin et al., 1990; Fowler et al., 1994, Swatman, 1994, Swatman et al, 1994; Venkatraman, 1991). The extent of EDI integration with internal and external business processes (Bergeron & Raymond, 1992) as well as with core business activities (Cox & Ghoneim, 1996) has been identified as a determining factor in achieving maximum business benefit. The third perspective is concerned with the impact of EDI on organizations. In particular, organizational benefits associated with EDI implementation have been widely (Cox & Ghoneim, 1996; Reekers & Smithson, 1993, 1994) investigated in terms of its impact on reducing transaction costs, increasing operational efficiency and enhancing competitive capacity. The fourth perspective concentrates on implementation issues. The role of Strategic Information Systems (SISP) planning in the successful adoption of EDI has been highlighted (Galliers et al, 1995). Critical success factors in adopting EDI have been explored and various implementation models have been described which highlight both internal and external organizational requirements (Cox & Ghoneim, 1996; Holland et al, 1992). 3 Finally, there is a further perspective which takes a technological approach to the discussion of EDI (Borthwick & Roth, 1993). Here technological solutions are sought to technological obstacles which are viewed as being the primary barrier to successful adoption. Each of these perspectives highlights important aspects of the EDI implementation process. However, there is no single, coherent theoretical framework which covers the complexity of the entire process. The difficulty of establishing a single EDI adoption and implementation model stems from the diversity of EDI applications across various business domains, EDI’s inter-relatedness (dependence) with inter and intra-organizational business requirements, as well as its impact on inter organizational systems and internal business processes. Lack of guidance is a major impediment facing nations, sectors and organizations in the early stages of adopting EDI. The situation is the result of the limited research into EDI specific technology transfer issues and the limited efforts into developing generic EDI adoption models or implementation guidelines to identify transferable organizational, sectoral and national lessons from sophisticated and mature EDI markets. OBJECTIVES The main objectives of this paper are two fold: First, to identify the factors that influence success in IT facilitated trade processes, particularly within the framework of introducing EDI to nations in the early stages of formulating their EDI and electronic trading policies. Second, to clearly define nation-specific requirements within a clearly defined multidisciplinary implementation framework, as in the case of Egypt, and determine the respective policy implications. SCOPE This paper is based on research conducted in Britain into the critical success factors for successful EDI implementation at an organizational, industrial and national level. The results of this previous research (Cox & Ghoneim, 1994,1995,1996) have been compared, contrasted and integrated with results of research conducted both in the United States of America and Germany (Banerjee & Golhar, 1991; Reekers & Smithson, 1994). In this paper the CIC framework is briefly described and applied in a case study of the Customs and Excise 4 Authority in Egypt where intense pressure exists to move towards compliance with international standards and changing trade practices. This paper is founded on two major studies into developing a national EDI strategy: namely, Schware and Kimberley - a World Bank study conducted in 1995, and Cox and Ghoneim research conducted over a five year period at Imperial College, London into the factors that influence and are influenced by EDI adoption in a national setting. Both studies aim to define ‘best practice’ measures of introducing EDI within a trade facilitation framework. The following section introduces briefly the salient features of the two studies. Best Practice As defined by Schware and Kimberley (1995) – “The purpose of best practice within the context of trade facilitation is to replace paper documents with electronic equivalent, but not in an exact substitution.” Properly designed, an EDI system will streamline documentation procedures and retool practices among the parties involved in the trade and transport procedures. The concept of replacing paper documents with EDI, representing much of the detail with codes and harmonized processes (trade facilitation), and the simplification of procedures (reengineering) represents the complete IT facilitated trade process (Schware and Kimberley, 1995). Schware and Kimberley (1995) The study focused on examining the extent of EDI global presence and the various implementation modalities. The authors defined the various implementation modalities as follows: w w w w w An approach driven, funded and managed by the government; A strong cooperative arrangement, driven either by a government department or by a joint venture with the private sector; A private sector-driven initiative based on existing competitive infrastructure, possibly in cooperation with a nationally approved mandated facilitating organization; A range of random leaderless examples; Very little or no activity. Such classification is very valuable as it implicitly provides the various scenarios and associated risks and gains. The authors also publish a separate report as a guide to best 5 practice (Schware & Kimberley, 1995b) where they focus particularly on the implementation aspects, namely: the legal and regulatory requirements; the skills and technology infrastructure; local business considerations; investment costs and benefits; technology and cost options. Cox and Ghoneim Cox and Ghoneim suggest that developing a national EDI adoption framework should not be confined to addressing technical transfer requirements. To maximize potential benefit, a national strategy will have to take into account the context in which the development of the EDI industry is undertaken. It must consider the nation’s particular political and economic goals and constraints, the business culture, sectoral structure as well as the organizational domestic and international requirements that may influence or be affected by the adoption of EDI. The authors develop a set of independent principles for analyzing EDI which could serve as a framework for undertaking an in-depth analysis of factors that influence and are influenced by EDI adoption on a national, industrial and organizational level. The authors discuss the importance of considering the 'Context' (political, economic and social environments); the 'Infrastructure' (technical requirements and know-how) and the 'Capacity to Change') in developing a national EDI strategy. These elements are integrated in the CIC framework (Figure 1) which is applied to Egypt. The CIC is a multi-dimensional research framework which attempts to convey the complexity and inter-relatedness of the business and technical determinants of successful EDI implementation. 6 Figure 1: CIC Framework Context Context Infrastructure Infrastructure Technical TechnicalImplementation Implementation Capacity Capacity totochange change EDI EDIAdoption AdoptionModel Model National NationalEDI EDIStrategy Strategy National National Organization Organization Characteristics Characteristics&&Requirements Requirements Characteristics Characteristics&&Requirements Requirements Industry Industry Characteristics Characteristics&&Requirements Requirements The proposed framework establishes the major criteria to be considered when adopting EDI. This study does not call for a universal EDI strategy, but asserts that a successful EDI strategy must grow out of a sophisticated understanding of the surrounding business and technical requirements and structure and how they are changing. Furthermore, only strategies tailored to the particular business requirements, to the inter and intra systems and processes and flexibility to accommodate change succeed. THE CIC FRAMEWORK Successful development of a national EDI strategy requires that an analysis be undertaken of the Context, Infrastructure and Capacity to Change. We examine each of these factors in turn and discuss their importance within the Egyptian context. Contextual Environment for EDI The proposed CIC framework is demand driven, and as such primary emphasis is placed on clearly defining the ‘contextual’ business requirements driving EDI adoption. Successful EDI implementations have been in response to demand pull conditions where nations adopting EDI were either driven by increased Globalization and regional integration pressures translated into trade facilitation initiatives, or by national business requirements. The UK experience reflected the criticality of responding to national business requirements. Business requirements on a national, industry and corporate level have been key to successful EDI adoption. It is crucial to acknowledge that the ‘contextual’ influences will not only vary from one nation to another, but also according to specific industry requirements and different corporate 7 objectives. Of primary importance, on a national level, are the political, economic, social and business environments and the role of Government. Infrastructure and Know-how EDI technical infrastructure, by definition, involves not only information technology resources, but also telecommunications platforms and legislative aspects to govern inter-organizational relations. At the national level, the legislative aspects as well as the national information technology and telecommunications infrastructure, in general, and the role of value added networks and coordinating bodies, in particular, have to be investigated. Capacity to Change Change is continuous, and nations, industries and firms are all under pressures to accommodate both changing business and technical requirements. On a national level there is continuous change in policy to accommodate dynamic international trade requirements. Within industry sectors, there is a continuous requirement for integrating new EDI applications with existing or reengineered business processes. Meanwhile, organizations are under pressure to provide better services/ products under stringent cost controls and highly competitive markets and as such are continuously changing their production strategies and corporate processes and practices. Exploiting EDI’s technical capacity to accommodate changing business and technical requirements has been identified as a critical success determinant in developing an EDI strategy. In this paper ‘capacity to change’ refers to EDI’s technical ability to accommodate changing business and technical requirements. Applying the CIC framework is suggestive of the fact that although there are a number of lessons to learn from the mature EDI markets in the West, criteria for technology transfer must be well defined to ensure that nations gain maximum benefit from EDI adoption. For example, applying the standard supply driven approach which focused only on infrastructural technology transfer issues in developing a national EDI industry, substantially delayed the development of the EDI industry in Egypt, because it failed to incorporate the nation-specific requirements. THE CASE OF EGYPT CONTEXTUAL ENVIRONMENT FOR EDI As shown in Figure 2 and detailed hereunder, a number of motivational factors influence the decision to adopt EDI on a national level. These factors stem from the political, economic, social and technical environment. 8 Figure 2 – EDI Contextual Pressures Economic Social Technical Political External Environment Business Requirements National Regulations National Organisations EDI National Strategy Infrastructure P E R F O R M A N C E Political environment. It is crucial that due attention be given to the political environment into which EDI is to be introduced. Of primary importance is the role of Government in establishing successful national EDI strategies. Singapore is a clear example of a successful Government sponsored EDI initiative whereas Latin America has achieved limited success with trade facilitation initiatives primarily due to the lack of serious Government intervention (Schware & Kimberley, 1995). In Europe there have been a number of initiatives both national and international, aimed at establishing European-wide EDI policies and standards. The European Commission has, for example, allocated ECU 30 billion to spend over the next 10 years to establish a panEuropean EDI infrastructure. Likewise, Egypt is under pressure to extend IT policy in general and EDI specifically. A World Bank study conducted in 1995 endorsed the use of EDI and electronic commerce as critical components in trade facilitation. Based on this study recommendations were put forward to the Egyptian Cabinet of Ministers in May 1997 which identified a number of immediate priorities to boost Egypt's trade performance as part of a continued pursuit of trade and the promotion of foreign direct investment (FDI). These recommendations were primarily concerned with introducing customs, inspection, regulatory and procedural reforms to strengthen Egyptian competitiveness in the world markets, accelerate the pace of moving goods into and out of the country, improve the reliability of importing and exporting processes, and generally reduce the transaction costs of exporting. Although, considerable effort has been made by the Egyptian Government to enhance the transparency of trade procedures, this remains problematic. The Egyptian Government has 9 now lent its support for the implementation of EDI but sees its role as a regulatory one, securing funding and providing the required infrastructure, rather than implementational. Economic environment. Trade liberalization and economic transformations in recent years have necessitated the review of existing systems used for processing trade documentation. In Europe, the emergence of the Single European market is a good example of this. Prospects for faster economic growth in the Middle East and North Africa, in particular, have been associated with the ability of policy makers to hasten integration with the world commodity and capital markets through structural adjustment and trade liberalization. Egypt as a member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is committed to participation in the international markets for goods, services and capital. This commitment involves liberalizing imports, promoting exports and encouraging foreign direct investment. Such development strategies entail removing barriers to trade that require reforming traditional standards, procedures and agreements, which facilitate international trade. For example, members of the WTO must abide by the requirements for custom valuation which implies that Egypt will have to alter existing customs valuation . Social environment. Studies in Europe and The United States of America have highlighted the power of the business community to drive forward the adoption of electronic trading standards (Banerjee & Golhar, 1991; Reekers & Smithson, 1994). For instance, in Britain the success of the introduction of EDI may largely be attributed to the pressures exerted by the business community to establish standards. The United Kingdom initiated EDI for trade facilitation purposes early in the 1980's. The British Simpler Trade Producers Board (SITPRO) and the UK Article Numbering Association worked towards developing TRADACOMS which is a national standard and which caters for domestic business requirements. Egypt is coming under increasing pressure from the business community to adopt information technologies, which will allow it react more flexibly, and promptly to changing market demand. Due to recent increased awareness of the business benefits associated with electronic commerce in general and EDI in particular, members of the business community in the Federation of the Egyptian Industries (FEI) and members of various chambers of commerce are pursuing different avenues to acquire new trading technologies. Technical pressures. Egypt as a member of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), is a participant in the trade efficiency program which is designed to enhance trade systems and services through the creation of a network of Trade Points in each of the 10 participating nations. Besides creating trading networks, Trade Points also provide trading facilities and linkages, and promote the introduction of EDI. Egypt as an emerging market is also a recipient of aid, particularly allocated to electronic systems upgrading and IT-specific technology transfer. Technical pressures to adopt information technologies (such as electronic commerce and EDI) and new logistics (such as JIT and QR inventory control) were primarily supply driven in the early 1990s by international organizations in an attempt to exploit the funds allocated. Lack of awareness of the potential business impact of such technologies on the one hand and lack of domestically rooted demand driven initiatives on the other substantially delayed serious developments to establish national value added service networks in Egypt. INFRASTRUCTURE The extent to which a nation is able to adopt a new technology is heavily dependent on the state of its existing infrastructure. "In 1985, Egypt had the vision to develop solid strategy to build the information infrastructure" (El Sherif, 1996). Part of this strategy was achieved through establishing information and decision support centers at both central and local government levels. In addition nationwide databases were developed and major improvements in both telecommunications and informatics achieved. Strategic alliances were formed with international high profile world leading organizations in information technology and close bilateral co-operation with European Union countries was established to share experience and know-how (El Sherif, 1996). In addition, Egypt has participated in the UNCTAD's Trade Efficiency Program, aimed at establishing a worldwide network of trade facilitation centers called Trade Points. These trade points are laboratories where the latest information and telecommunications technologies, such as EDI, are applied to trade (UNCTAD, 1992). It is interesting to note, however, that Trade Point's plans to introduce EDI to the Egyptian market did not materialize. Trade and information technologies have been confined to data provision; Trade Point, located within the Ministry of Industry, services are limited to the provision of data sets and reports on national and international trade trends. EDI services in Egypt are limited to access to international service providers. Neither the philosophy nor the facility is available on a national basis. Use is confined to a limited number of multinationals committed to communicating with parent companies or trading partners. Dependence is primarily on one service provider. Experience in those countries where EDI has been successfully implemented highlights the importance of the role of EDI coordination authorities and value added network service providers. Organisations such as EDIform in the Netherlands, and the EDIA (EDI Association) in the UK play a crucial role in co-ordinating activities. Egypt, likewise, requires the appointment of a national EDI service provider as well as a single, well funded, one stop trade promotion agency with strong affiliations and networking capacity with various trade bodies. 11 CAPACITY TO CHANGE A major determinant to the success of a national EDI strategy is the initiators awareness of EDI’s capacity to accommodate nation-specific changing business and technical requirements. International trade processes are typically characterized by complexity and redundancy. Some document handling procedures are surrounded by 500-year-old practices. A typical international trade transaction can take as many as 150 different documents to process (Schware & Kimberley, 1995). Meyers & Canis (1991) indicate that there are estimates of paperwork in international trade costing some 7 percent of the value of the goods traded. This complexity is not only as a result of the multiplicity of organisations involved in the supply chain, but is also a product of multiple data entries. Although EDI can play an effective role in reengineering such processes, the environment constraints are likely to inhibit such changes. For example, India, where resistance to change is strong committed itself in 1993 to domestic EDI usage, but in 1995 there were no more than 200 users in the region (Schware & Kimberely, 1995). Meanwhile, where initiatives accounted for EDI’s capacity to change to accommodate changing business and technical requirements, successful results were reported. For example, Western countries such as France, Ireland, Germany, Spain , Switzerland and Benelux countries have focused on defining EDI requirements ensuring connectivity and compatibility as well as primarily adopting EDIFACT to ensure homogeneity and integration with international standards to account for potential changes in the business and technical requirements. The EDIFACT development in itself is an example of a regional initiative reflecting a European orientation and compliance with business requirements and cross border trade facilitiation objectives, which has influenced EDI adoption and organization migration from national initiative to EDIFACT as in the case of the United Kingdom,. Developments and changes in standards developments reflect on EDI’s flexibility in accommodating changing business and technical requirements. Furthermore, on a national level there is a continuous change in policy to accommodate dynamic international trade requirements and as such appropriate appreciation of EDI’s capacity to accommodate such changes are critical to success. Competitiveness depends on the ability to meet changing market requirements and the flexibility to meet changing demands for products and services. In particular, the infrastructure and procedures that enable both importers and exporters to access and exchange products and information efficiently and effectively are critical to a nation’s competitive position/ capacity. Yet, process change, in particular international trade procedures represent a major challenge in trade facilitation initiatives. 12 It is therefore recommended that initiators awareness is not confined to EDI’s technical ability to streamline procedures as a part of a major reengineering strategy, but also encompasses EDI’s potential to accommodate change and as such allow for a phased approach to account for the existing environmental constraints. This understanding provided the foundation of the proposed solution to the Customs and Excise Authority in Egypt suggested in the following section of the paper. THE EGYPTIAN CUSTOMS AND EXCISE AUTHORITY Egypt's Customs and Excise Authority (CEA) was established in the early nineteenth century (1819) as the legitimate gateway for imports and exports. The CEA mission has focused, since its inception, on generating revenues for the national treasury through duties applied to imports and exports. Customs duties alone have accounted for approximately 30% of tax revenues over the past 5 years and 12% of all government revenues (World Bank Report, 1997). Consequently, the efficiency of customs revenue collection is crucial. Egypt's CEA is organized along four geographical directorates, namely: Cairo, Alexandria, Suez and Aswan. Each directorate is responsible for the gateways at Egypt's borders with the outside world. Within each directorate, several CEA outlets exist, e.g. the Alexandria directorate handles both Alexandria and Damietta seaports in addition to Egypt's Western borders with Libya. Each directorate is organized around two functional layers: the operational and financial layers. The operational layer is mainly responsible for the validation of regulatory permits and documentation as well as the valuation of goods and the application of various duties and taxes, whereas the financial layer is primarily concerned with duty collection and management of warehouse transactions. Each directorate has distinct functions and features, dependent on the type and value of goods exchanged. For instance, in terms of transaction volume, the Cairo directorate handles around 300,000 consignments each year, whereas Alexandria handles only 70,000 annually, however, in terms of value, Alexandria handles 82% of the total value of goods imported and exported. Consequently, automation was initially launched in Alexandria which has evolved as the Central Computer Department (Zorkani, 1996). Since the inception of the process of automation at CEA, initiated in the mid 1980s through a French Government initiative, the focus has centered around Alexandria, being the largest revenue generator. Since then, only 12 other outlets have been automated while the majority of outlets are still based on manual processes. 13 As Egypt embarks on a new era of economic reform, the accelerated need for exports to offset the deficit in the trade balance on the one hand, and the challenges posed by GATT to developing countries on the other has meant that, the role, mission and objectives of Egypt's CEA is undergoing a rapid change. Progress in achieving this desired change is hindered by numerous inspection agencies and layers of regulations which slow the movement of goods to and from international markets, hinder trade promotion, administrative efficiency and encourage theft and fraud. Flow of Information Through Egypt's Customs and Excise Authority CEA Problems of information flow within CEA are typical of those encountered by institutions involved in international trade, namely, lack of detailed data and a series of complex processes in need of streamlining utilizing state of the art technologies. Analysis of the existing flow of information through CEA suggest that enhancements can take place with respect to logistics and data handling which would result in substantial financial savings (Zorkani, 1997). Areas of reform focused on: A. Requirement for Detailed Data There is a fundamental requirement for detailed product information. The existing systems cater only partially for such requirement. As a result, there is often inconsistency and discrepancy in the information reported particularly with respect to the estimated versus the actual revenue collected. B. Streamline Processes A long and tedious paper based system, by definition, lends itself to error. The presence of multiple agencies and multiple layers within each agency in the processing of information result in inconsistency in the data reported. Lack of systems transparency and consistency in procedures with respect to which regulations apply and rationale for change contribute to systems complexity and ambiguity. Customs officials indicate that clearance procedures could be streamlined and that substantial savings in the attendant time and costs could be achieved. The Government is seeking to introduce of new procedures that utilize modern information technology that will effectively facilitate trade. 14 C. Organizational challenges Egypt's CEA would clearly benefit from the introduction of EDI, however, major strategic and organisational barriers exist: First, the CEA organizational and cultural setup, as with other customs authorities worldwide, is fairly complex and rigid and there would be considerable resistance to alter inter and intra organizational power relations. Second, the peripheral outlets (which are still manually operated) and which report to the centralized systems, have enjoyed a grace period of delay of one to three months to complete any one operation and their fear of change is likely to inhibit any fundamental structural reengineering programs. Third, the strategic alliance in place with the French organization in charge of operating and maintaining the central computing department is funded by the French Government which has recently renewed its funding and maintenance contract of the system till 1999. This alliance does not allow for any tampering with the existing system nor is it flexible (Zorkani, 1997) Given the national drive to integrate into the global economy and the existing organizational and cultural constraints at CEA the following section proposes a staged approach to introducing EDI within the Customs and Excise Authority in Egypt. PROPOSED SOLUTION Although a fully-fledged EDI implementation strategy together with a fundamental business process re-engineering initiative may contribute significant benefits to the CEA, the given constraints do not allow for such privilege. However, an initial phased approach leading eventually to business process re-design may be introduced through the simple application of an EDI system, external but parallel, to the CEA flow of information processes which shadows the data processed. This would be transparent to the public, but avoid the major threats associated with a new implementation. A PHASED APPROACH: A three- phased approach to meet CEA specific barriers and challenges is proposed: Phase I - EDI Introduction. This initial stage of EDI implementation aims at capturing detailed consignment details without tampering with the existing systems. This introductory stage is proposed in which EDI is used to shadow existing process. The warehouse audit control system will ensure the capture of detailed consignment data which will then be electronically processed and await the goods 15 release authorization which will in due course be deducted from the debit manifest according to the consignment details. This minor alteration does not interfere with any of the operational layer processes but provides the following benefits: Detailed line items will be received from the shipper prior to docking which will provide immediate access to information, cut down on time delays, include a complete record of information including customs code and product description and provide control of warehousing inventory. The automatic tracking of products in process versus products released will be much better controlled and thus reduce opportunities for inconsistent in data or discrepancy. Similarly, dumping processes will be better controlled. Audit for valuation of import goods could take place in advance, since details of a shipment would be available prior to the actual docking of the goods. This will enhance systems’ transparency. This proposed system would also provide a more centralised audit of the functions of the CEA and help set the stage for expanding this pilot phase to a full and comprehensive EDI implementation. This pilot could be further extended to provide an enhancement to the existing paper process by enabling a pre-set form to be printed for importers upon submission of consignment. Although, the proposed initial phase is confined to producing accurate data and providing initial information control, it provides the potential to streamline business processes, and provide the initial control over the identified system loopholes. Phase II - EDI Development/ Diffusion. The second stage of the proposed solution aims at establishing the foundation for developing the national EDI community. This phase would be set up at the operational level and would entail the use of a PC terminal at the initial stage of the clearance process. A unique reference could automatically be generated on the Import Clearance Application Forms, which would result in the elimination of the final CEA central registration process in Alexandria. This will also facilitate communication with the importer or his broker, increase efficiency (avoid data inconsistency and procedural delays) and enhance the CEA services. Networking of PC's may be considered at a later stage. Such application would, however, require development and upgrading of the skills, knowledge and expertise of existing staff. 16 Phase III: Establish an EDI Gateway Ultimately the CEA would benefit from the implementation of a full-fledged EDI implementation. Such implementation would, however, involve simplifying processes, removing excessive and obsolete controls, shortening and easing lines of communication and using both bar-coding and EDI for rapid, accurate transfer of data between computers. It would also require alignment with trading partners' systems and the adoption of international electronic commerce standards. However, given the existing constraints this may only be considered as a long-term strategy. Figure 3 – Full EDI solution Discussion The introduction of EDI within a trade facilitation framework would not only reap efficiency gains, in terms of use of accelerated, simplified systems and EDI preclear imports and exports, but would also provide the information necessary for decision making with respect to problem solving, facilities scheduling, and planning for maximum use of infrastructure. Such implementation would not only contribute towards Egypt’s integration in the global economy, but would also cater for increasing the revenue generated by Egypt’s CEA as a result of increased efficiency and enhanced transparency of the procedures involved in international trade. Egypt is an emerging market that is heavily investing in development and growth strategies based on trade and foreign direct investment promotion and streamlining of associated 17 processes. EDI provides the capacity to cater to Egypt’s trade facilitation requirements and offers the potential for some dramatic national performance as witnessed by the evidence of success in Singapore. EDI’s role in endorsing national strategies and safe guarding national interests should provide the basis of developing a long-term strategy in spite of the presence of major implementation barriers. As proposed, a simple EDI implementation scenario may be adopted in the short term to overcome immediate problems, cater to information availability, and provide management and control to serve the immediate trading process efficiency requirements. Lessons Learnt The issues discussed above contribute to the understanding of the issues critical in developing a national EDI strategy. The following section highlights the salient features: Business requirements. In line with the CIC framework, the development of the EDI strategy is demand driven to cater to national requirements. The proposal for a phased implementation solution, is driven by business requirements to fulfil the trade facilitation initiatives, integrating the core business application identified as the information contained within shippers documents, and considering the inhibiting barriers a proposed flexible solution that may be potentially developed in the future into a full-fledged EDI corporate gateway is proposed. Inspite of acknowledgement of the role and impact of EDI in enhancing business operations, the supply driven approach to develop a full-fledged EDI industry did not make progress in Egypt. However, demand driven requirements to implement EDI as a trade facilitation tool in order to further integrate the country into the world economy in general and to facilitate international trade procedures in particular, is providing the project with the necessary national and international endorsement to ensure its successful implementation. The debate today is no longer about whether or not to adopt EDI, but how best to utilize EDI to integrate into the world trade and financial markets. Consequently, EDI implementation is considered at the highest policymaking and senior management levels. Part and parcel of the requirements is a phased approach to meet CEA specific barriers and challenges, which has been catered to proposing a three-phased approach. The first introductory role includes a parallel shadow streamline to overcome existing barriers and provide system accountability, enhancing CEA accessibility to detailed data and indirectly controlling theft and fraud. In the second stage, community development, the use of EDI is extended to importers to enhance efficiency and promote an electronic trading culture. In the third stage, development of a CEA EDI Gateway will provide for a full-fledged EDI operation 18 based on a business process redesign and quality management strategy to bring Egypt in line with international efficiency standards. Unlike the initial implementation phases, implementing a corporate EDI gateway would involve fundamental changes in procedures and processes. Role of Government. The regulatory role of government and its endorsement of developing EDI through securing funding and required infrastructure, will be instrumental in project ramp up. The Government of Egypt played a leading referee role rather than an implementational one in the initial stage of introducing EDI. Following on from the Singapore experience, Government endorsement of electronic trade in general and EDI in particular is instrumental in promoting and institutionalizing EDI adoption nation-wide. Trading Partners Requirements. To ensure successful implementation, incorporating trading partners requirements is also crucial. The success of Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise Authority in the United Kingdom in endorsing electronic trading has been in addressing and integrating its trading community requirements in all activities related to the collection and dissemination of information (Sawhney and Williams, 1994). Such partnership can be seen as a fundamental requirement to facilitate later phases of EDI implementation and community development. Accommodating for trading partners requirements, particularly in terms of standards compatibility is crucial in developing the EDI community. Technical strategy. Technology transfer, with respect to actually developing a national EDI industry in general or adopting EDI on an organizational or institutional level is not problematic. In fact, some immediate technical alternatives, such as using EDI on the Internet, is available to hand. However, in order to successfully and systematically develop a national EDI community, it is important that to have a national vision and a clear strategy as in the case of Singapore. It is also asserted that the strategy should not be confined to the technical aspects, but also include the ‘know-how’ critical to successful development such as the role of Value Added Network Services (VANS), EDI associations and co-ordinating bodies is founding a national EDI industry. It is worth noting that the wide-use of the Internet is also potentially providing small and medium size enterprises with a cost effective means of adopting EDI. There are some serious legal and security implications related to the use of electronic trading on the Internet, which lies 19 beyond the scope of this paper, yet technically the Internet may provide an interim stepping stone towards the full appropriate adoption of electronic trading. Policy Implications The study conducted by the authors suggests that the success of outlining a national EDI strategy will primarily depend on integrating business requirements, Government intervention, infrastructure efficiency and capacity to change to cater for changing market and technical requirements. Estimated costs and changes to regulations are outside the scope of this study, given the complexity in accounting for the anticipated variation across nations. The main policy implications can be summarized as follows: A demand-driven national EDI strategy must be based on well defined national business and economic needs and requirements, to incorporate international requirements to streamline trade processes to reduce the trade information processing cycles to a minimum critical path thus achieving maximum economies and optimum trade competitive advantage (Schware and. Kimberley, 1995) or to cater to the requirements of national industry sectors, based on their perceived competitive and efficiency benefits. Unless there is recognition of business drivers as the main motivational factors to adopt EDI, limited benefits will be accrued. INCREASE AWARENESS AND ENHANCE EDI-SPECIFIC EDUCATION . Expert knowledge of business requirements and EDI capacity is a pre-requisite to successful implementation. Schware and Kimberley (1995) endorse the requirement for increased awareness and education and call for the establishment of an awareness and education program as possibly the most important key to success. They assert that lack of such a program is most likely to cause failure and delay EDI implementations. Promoting EDI education will contribute towards human capacity building. It will not only help develop the skills and expertise required for maximizing the use and potential of EDI implementations, but also cater for tailoring EDI use to national requirements and constraints. . Furthermore, a national EDI initiative must be based on a strategic plan and a shared vision of the outcome and benefits. This form of leadership and commitment at the highest policymaking levels, in collaboration with the business community having a unified commercial interest, will ensure successful EDI diffusion across the various industry sectors. 20 Role of Government. The role of Government is instrumental in developing the EDI industry infrastructure, particularly in the early stages of development. The Government’s capacity to alter regulations to accommodate electronic trading requirements, to secure funds or act as a catalyst in developing the EDI community by endorsing an intergovernmental and/ or public sector electronic trading strategy is invaluable. Development of the infrastructure does necessarily need to be centrally funded by the Government, but could be in the form of an endorsement or partnership with the private sector. The most important aspect is to institutionalize electronic trading and ensure a conducive environment for community development. In some cases, such as in developing countries, because of the initial size of the market, or because of technology transfer restrictions, it may be necessary for the Government to fund the value added network service or undertake its duties in the initial stages of establishing the EDI industry. National Infrastructure Development. A primary requirement for developing a national EDI industry is the availability of a sufficiently sophisticated, competitive and reliable data communications network and value-added network services as previously discussed. Although the EDI technology itself is transferable, local expertise is still required to apply domestic requirements, definitions and restrictions. This is applicable in terms of defining EDI applications and standards as well as in developing the marketing and community development strategies. Developing the infrastructure should also take into account the know-how transfer to include factors critical to successful EDI adoption on a national level including the role of VANS and EDI associations. Capacity to Change. The national strategy should include an institutional mechanism for monitoring and tracking changing business and technical requirements in order to cater for the required changes, in legislation for example, effectively and efficiently. CONCLUSION 21 This paper discussed the issues critical to developing a national EDI strategy to aid nations in the early stages of adopting EDI. Introducing EDI within trade facilitation initiatives, in Customs and Excise applications specifically will not only reap efficiency gains but also embrace national goals to integrate in the global economy and increase revenues generated as a result of increased efficiency. Critical to successful EDI implementation is accommodating the contextual environment and not confining the strategy to technology transfer to building the EDI industry. The foundation must be demand driven to cater to specific national requirements, defined within a clear national strategy as in the case of Singapore. It is estimated that successful implementation of EDI within the CEA in Egypt may result in increasing the revenue generated by the authority by a $350 million annually (Zorkani, 1997). The research findings also indicate that Government endorsement of electronic trading is instrumental in founding the legal and technical infrastructure of the EDI industry at large. Finally, careful consideration needs to be given to existing procedures and attitudes to change as illustrated in the CEA case study. The extent of awareness of EDI benefits and capacity to accommodate change is also critical in developing the national EDI strategy. Acknowledgement The authors would like to thank Mr. Hatem Zorkani for his invaluable input to the study of the Customs and Excise Authority in Egypt. References Banerjee, S. and D.Y. Golhar. (1991) Electronic Data Interchange in U.S. firms: A Survey. Report, Drexel University. Benjamin R.I., De Long D.W. and Scott Morton M.C. (1990) “Electronic Data Interchange: How Much Competitive Advantage.” Long Range Planning 23(1):29-40. Bergeron, F. and L. Raymond. (1992) “The Advantages of Electronic Data Interchange.” Database (Winter): 19-31. Borthick, A. F. and H. P. Roth (1993) “EDI for Reengineering Business Processes.” Management Accounting, 75(4): 32-37. Cash, J. I and B. R. Konsynski. (1985) “IS redraws competitive boundaries.” Harvard Business Review (March-April): 134-142. 22 Cox, B. and S. Ghoneim. (1994) “Benefits and Barriers to Adopting EDI in the UK: A Sector Survey of British Industries.” In Proceedings of the Second European Conference on Information Systems, 643-654, The Netherlands. Cox, B. and S. Ghoneim. (1995) “Developing an EDI Strategy: Transferable Organisational and National Lessons from the UK Experience.” In Proceedings of the Information Technology for Development, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Cox, B. and S. Ghoneim. (1995) “Implementing a National EDI Service: Issues in Developing Countries & Lessons from the UK.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Socio-Economic Development: Challenges & Opportunities,125-147, Cairo, Egypt. Cox, B. and S. Ghoneim. (1996) “Drivers & Barriers to Adopting EDI: A Sector Analysis of UK Industry.” European Journal of Information Systems 5:24-33. 0960-085X/96 Cox, B. and S. Ghoneim. (1996) “Extending the Role of EDI: The HMSO Case Study.” In Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Information Systems, 1185-1195, eds. J. Dias Coelho, T. Jelaasi, W. Konig, H. Kremar, R. O’Callghan, M. Saaksjarvi, Lisbon, Portugal. Cox, B. and S. Ghoneim. (1997) “Developing a National EDI Strategy.” In Business Information Technology Management: Closing the International Divide, eds. Banerjee, P., R. Hackney, G. Dhillon and R. Jain, 320-336, Har-Aanad Publications PVT Ltd. Cox B. and S. Ghoneim. (1998) “Strategic Use of EDI in the Public Sector: The HMSO Case Study” Journal of Strategic Information Systems – forthcoming. El Sherif, Hisham. (1996) “Electronics and IT – The Road to Development.” German Arab Trade 58-60. German Arab Chamber of Commerce Report. Farhoomand, A. F. and E. Pace (1995) “An Exploratory Investigation of Electronic Commerce Use in International Trade”. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Information Systems, 33-41, eds. G. Doukidis, B. Galliers, T. Jelassi, H. Kremar and F. Land, Athens, Greece. Fowler, D.C., P.M.C. Swatman and P.A. Swatman. (1994) “A Corporate EDI Gateway: A Centralised Approach to Integrating EDI.” In Proceedings of the “ACIS’94” - 5th Australian Conference on Information Systems Conference, 43-56, Melbourne, Victoria. Galliers R., P. Swatman and P. Swatman. (1995) “Strategic Information Systems Planning: Deriving Comparative Advantage from EDI.” Journal of Information Technology, 10 (3):149-159. 23 Holland, C.P., G. Lockett, and I. Blackman. (1992) “Planning for Electronic Data Interchange.” Strategic Management Journal 13: 539-550. Johnston, H.R. and S.R. Carrico. (1988) “Developing Capabilities to Use Information Strategically. “ MIS Quarterly 12 (1): 37-48. Kimberley, P. (1998) Internal report (unpublished). Meyers R. B. and R. J. Canis. (1991) “Preparing for the 21st Century with EDI and Bar Coding.” EDI World, 1(12): 35-40. Reekers N. and S. Smithson (1993) “EDI in Europe: A Comparative Study of Implementation and Use.” In Sixth International Conference on EDI &IOS in Bled, Slovenia, ed J. Gricar and J. Noval, 61-75. Kranj: Moderna Organizacija Reekers N. (1994) “EDI Use in German and US Organizations.” International Journal of Information Management 14 (5): 344-356. Reekers, N. & Smithson S. (1994). “EDI in Germany and the UK: Strategic and Operational Use.“ European Journal of Information Systems, 3(3), 169-178. Sawhney, V. and A. Williams. (1994) “Electronic Data Interchange in Government: The Business Opportunities.” Report, CCTA, The Government Centre for Information Systems, London. Schware, R. and P. Kimberley. (1995) “Information Technology and National Trade Facilitation – Making the Most of Global Trade.” World Bank Technical Paper Number 316. Schware, R. and P. Kimberley. (1995) “Information Technology and National Trade Facilitation – Guide to Best Practice.” World Bank Technical Paper Number 317. Swatman, P.M.C. (1994) “Business Process Redesign Using EDI: the BHP Steel Experience.” Australian Journal of Information Systems 2(1):55 - 73. Swatman, P. M. C., P. A. Swatman and C. Fowler (1994). “A Model of EDI Integration and Strategic Business Re-engineering.” Journal of Strategic Information Systems 3(1):4161. UNCTAD. (1992). Report on the Creation of a Trade Point in Egypt, Preparatory Mission, 20-22 (unpublished). 24 Venkatraman, N. (1991) ”IT-Induced Business Change.” In The Corporation of the 1990s: Information Technology and Organisational Transformation, ed. M.S. Scott Morton, Oxford: Oxford University Press. World Bank. (1997). Egypt: Trade Facilitation for Export Growth, - Export Development Seminar – Volume II, Background Papers. World Bank. (1997). Promoting Outward Orientation through Exports, Arab Republic of Egypt, Country Economic Memorandum – Egypt: Issues in Sustaining Economic Growth – Main Report (Volume II), World Bank Resident Mission in Egypt, Middle East and North Africa. Zorkani, Hatem (1996). Advisor Cabinet Information and Decision Support Center and Consultant to CEA Efficiency Development Program, interview. Zorkani, Hatem (1997). Advisor Cabinet Information and Decision Support Center and Consultant to CEA Efficiency Development Program, interview. 25