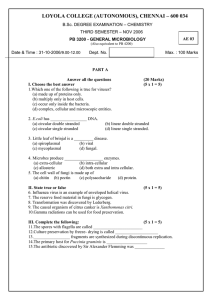

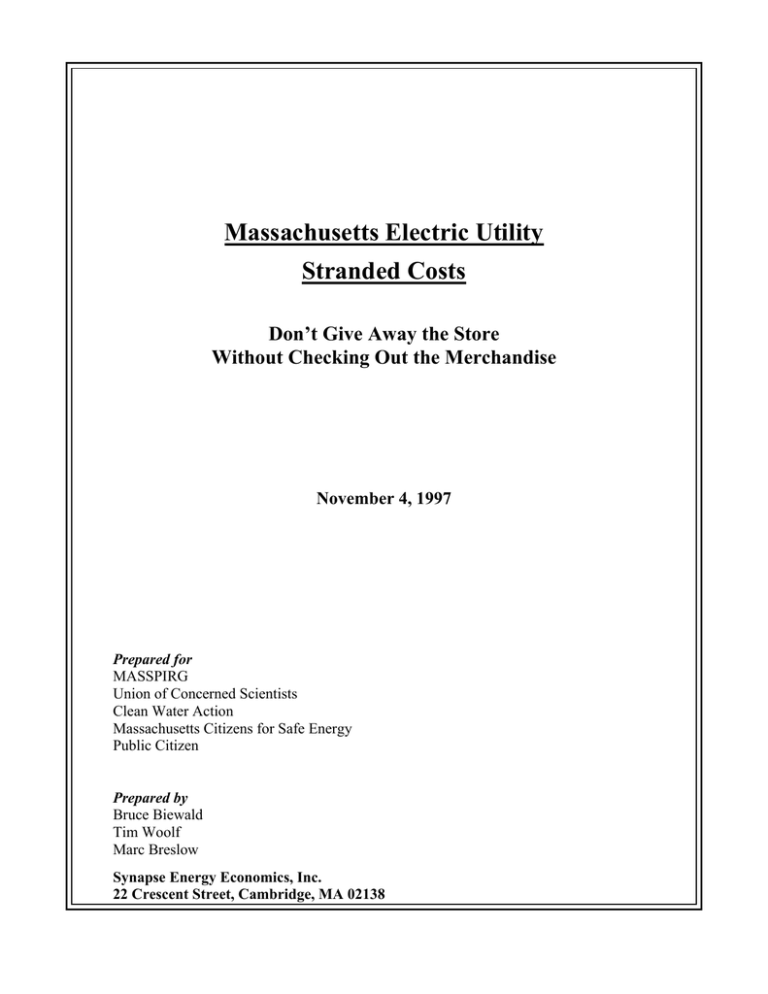

Massachusetts Electric Utility Stranded Costs

advertisement