Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Ocean & Coastal Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocecoaman

Designing a network of marine protected areas in California: Achievements, costs,

lessons learned, and challenges ahead

Mary Gleason a, *, Evan Fox b, Susan Ashcraft c, Jason Vasques d,1, Elizabeth Whiteman e, Paulo Serpa f,

Emily Saarman g, Meg Caldwell h, i, Adam Frimodig j, Melissa Miller-Henson b, John Kirlin b, Becky Ota d,

Elizabeth Pope j, Mike Weber k, Ken Wiseman b

a

The Nature Conservancy, 99 Pacific St., Suite 200G, Monterey, CA 93940, USA

Marine Life Protection Act Initiative, California Natural Resources Agency, 1416 Ninth St., Suite 1311, Sacramento, CA 95814, USA

California Department of Fish and Game, 1812 9th St., Sacramento, CA 95811, USA

d

California Department of Fish and Game, 350 Harbor Blvd., Belmont, CA 94002, USA

e

MPA Monitoring Enterprise, California Ocean Science Trust, 1330 Broadway, Suite 1530, Oakland, CA 94612, USA

f

California Department of Fish and Game, 20 Lower Ragsdale Rd., Suite 100, Monterey, CA 93940, USA

g

University of California Santa Cruz, 100 Shaffer Rd., Santa Cruz, CA 95060, USA

h

Center for Ocean Solutions, Stanford Law School, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, CA 94305-8610, USA

i

Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and Environmental and Natural Resources Law & Policy Program, Stanford Law School,

559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, CA 94305-8610, USA

j

California Department of Fish and Game, 619 Second St., Eureka, CA 95501, USA

k

Resources Law Group, LLP, 555 Capitol Mall, Suite 650, Sacramento, CA 95814, USA

b

c

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Available online 31 August 2012

The State of California recently planned and is implementing a network of marine protected areas (MPAs)

in state waters as mandated by the Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA). A publiceprivate partnership (the

MLPA Initiative) completed four regional public MPA planning processes characterized by robust

stakeholder contributions and the incorporation of best readily available science. Prior to enactment of

the MLPA in 1999, less than 3% of California state waters were in MPAs, and most of those MPAs were

small and lacked clear objectives. By 2013, approximately 16% of state waters will be in 124 MPAs that

represent and replicate most marine and estuarine habitats and are designed to be ecologicallyconnected. The redesigned statewide network of MPAs improves marine ecosystem protection in California, advanced the science and practice of designing MPA networks, and increased the awareness and

capacity of stakeholders, scientists and decision-makers for marine spatial planning. The public planning

effort took almost seven years and significant financial investment (approximately $19.5 million in

private charitable foundation funds and $18.5 million in public funds). Not all stakeholders were pleased

with the outcomes and the planning processes faced many challenges. While the design of the MPA

network aimed to meet science and feasibility guidelines, final decisions on MPAs in each region reflected tradeoffs needed to garner public acceptance and support for implementation. The MLPA

Initiative offers some key lessons about implementing policy through a public planning process. While

California is developing mechanisms for assessing effectiveness of the MPA network in coming years,

including establishing a MPA Monitoring Enterprise and a process for periodic review and adaptive

management of MPAs, significant challenges remain for effective implementation.

! 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ1 831 333 2049; fax: þ1 831 333 1736.

E-mail addresses: mgleason@tnc.org (M. Gleason), evanwfox@gmail.com (E. Fox),

SAshcraft@dfg.ca.gov (S. Ashcraft), jvasques@coral.org (J. Vasques), liz.whiteman@

calost.org (E. Whiteman), PSerpa@dfg.ca.gov (P. Serpa), emily@biology.ucsc.edu

(E. Saarman), megc@stanford.edu (M. Caldwell), AFrimodig@dfg.ca.gov

(A. Frimodig), melissa@resources.ca.gov (M. Miller-Henson), jkirlin@comcast.net

(J. Kirlin), bota@dfg.ca.gov (B. Ota), EPope@dfg.ca.gov (E. Pope), mweber@

resourceslawgroup.com (M. Weber), Ken.Wiseman@resources.ca.gov (K. Wiseman).

1

Present address: The Coral Reef Alliance, 351 California St., Suite 650, San

Francisco, CA 94104, USA.

0964-5691/$ e see front matter ! 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.08.013

Implementing networks of marine protected areas (MPAs) is

a primary conservation and management strategy worldwide, but

one that has significant socioeconomic, political, and scientific

challenges (Day, 2002; Fernandes et al., 2005; Green et al., 2009;

Osmond et al., 2010; Toropova et al., 2010). MPAs are controversial

with some stakeholders concerned about potential socioeconomic

impacts of eliminating or reducing fishing opportunities inside MPAs,

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

despite growing evidence that well-designed MPAs can contribute to

fisheries productivity and ecosystem benefits (Gell and Roberts,

2003; Lester et al., 2009; Gaines et al., 2010; Harrison et al., 2012).

While the science underpinning MPAs and their design to maximize

ecosystem and fishery benefits is rapidly evolving, it can be difficult

to implement MPAs at the size and scale recommended by scientific

literature, primarily due to resistance by affected marine resource

users and potential socioeconomic impacts (Agardy et al., 2003).

Involving stakeholders and the public in MPA design and implementation is critically important for their acceptance and effectiveness at meeting established goals, but requires significant investment

of funding and resources, especially at the scale of regional MPA

networks. While overcoming challenges to MPA network planning is

context dependent, careful documentation of successes and failures

can inform other similar processes, including emerging efforts for

more comprehensive coastal and marine spatial planning (Douvere,

2008; Ehler and Douvere, 2009; Halpern et al., 2012).

In 1999 the California Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA) was

enacted, mandating the redesign of California’s existing MPAs in state

waters (generally 0e3 nautical miles offshore and around islands)

into an ecologically representative network under the guidance of

a master plan (“master plan”). The MLPA has explicit goals, mostly

focused on ecosystem protection (Table 1). When the MLPA was

enacted, just 2.7% of California’s state waters were protected to some

degree in 63 MPAs, covering approximately 368 square kilometers of

state waters (Table 2, Fig.1). However, most of those MPAs were small,

located only near shore, allowed the take of many species (often with

confusing regulations), and provided limited ecological protection;

they were also established in an ad hoc manner and not designed as

a network (McArdle, 2002; Starr et al., 2002; Gleason et al., 2006).

The California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) led two

efforts to implement the MLPA between 2000 and 2002. Both

efforts were unsuccessful, mostly due to insufficient resources to

conduct a statewide participatory public process and lack of public

acceptance of initial MPA proposals developed largely by scientists

(Gleason et al., 2010; Weible, 2008). A successful, though controversial, public process to design marine reserves in state waters

around the northern Channel Islands resulted in a set of 13 MPAs

implemented in 2003 (and extended into federal waters in 2007),

which significantly increased marine protection in southern California (Table 2; Airame et al., 2003; Osmond et al., 2010).

In 2004, California launched a publiceprivate partnership, the

MLPA Initiative (Initiative), to guide the development of the statewide

master plan and to conduct regional planning processes to redesign

California’s existing MPAs. The publiceprivate partnership model

included a formal memorandum of understanding (MOU) specifying

roles of the public agencies and private charitable funding foundations, established expected deliverables and timelines, and created

a Blue Ribbon Task Force (BRTF) to oversee the process (Kirlin et al.,

2013). The Initiative process was designed specifically to bring

more capacity and resources to bear on the planning effort, conduct

planning regionally in a phased approach, put scientists in an advisory role, and involve stakeholders directly in the design of alternative MPA proposals (Gleason et al., 2010; Kirlin et al., 2013).

California’s statewide MPA network planning was conducted

through four regional planning processes for the open coast

2

MPAs in three regions (Central Coast, North Central Coast, and South Coast)

have been implemented; the proposed MPAs in the North Coast were adopted in

June 2012 and are anticipated to be implemented in early 2013. The Channel Islands

MPAs, designated in 2003, were found by the Commission to already be consistent

with the goals of the MLPA, and were integrated into the statewide network

unchanged. A planning process for the fifth region, the San Francisco Bay, will be

considered subsequent to completion of a water supply and ecosystem plan for the

Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta now underway.

91

between 2004 and 2011.2 Alternative proposals for the redesign of

existing MPAs and new MPAs in each region were developed by

a Regional Stakeholder Group (RSG) in an iterative process. Each set

of MPA proposals was evaluated by the MLPA Master Plan Science

Advisory Team (SAT), reviewed by the CDFG for design feasibility

and potential to meet MLPA goals, and guided by the BRTF. Multiple

stakeholder proposals in each region were refined to better meet

scientific guidelines and address feasibility concerns, while also

considering potential socioeconomic impacts and other considerations (Fox et al., 2013b). Alternative proposals from the stakeholders in each region therefore reflected a range in the number,

area, placement, and types of MPAs (i.e., “no take” state marine

reserves and “limited take” state marine conservation areas or state

marine parks).

The BRTF made recommendations for proposed MPAs in each

region, based on stakeholder proposals that had been formally

evaluated by the SAT and CDFG, to the California Fish and Game

Commission (Commission). The Commission, consisting of five

members appointed by the Governor with Senate confirmation, has

statutory authority to designate MPAs and issue associated regulations. The Initiative thus had an advisory role to the Commission

on MLPA implementation; however, the BRTF played a key role in

identifying a preferred alternative that reflected a balance between

achieving the goals of the MLPA and addressing specific issues of

each region and local uses of marine resources. The Commission

made final decisions on MPAs for each region after conducting

separate environmental and regulatory review processes with

additional, extensive public input (Kirlin et al., 2013).

California has designed and is implementing a statewide

network of MPAs that should, based on key habitats and areas

protected, make a significant contribution toward ocean protection.

The Initiative process also advanced the science and practice of

MPA network planning, tested a publiceprivate partnership

approach, successfully integrated science into policy, and built

capacity in stakeholders, scientists, and resource managers.

However, the regional planning processes also had significant

financial and socio-political costs, and uncertainty remains about

whether there will be sufficient long-term investment in enforcement, management and monitoring to achieve the anticipated

benefits of the statewide network of MPAs.

2. What was achieved in California’s MPA network planning

processes?

The Initiative developed a draft master plan3 to guide the

statewide design of the MPA network, and completed four regional

planning processes that provided specific proposals, analyses, and

momentum that led to decisions on implementing MPAs in state

waters by the Commission. The master plan was developed in

consultation with stakeholders and outlines the process for

developing alternative MPA proposals, includes science guidelines

on MPA design developed by the SAT, and provides an overview of

management, enforcement, monitoring, adaptive management,

and funding (CDFG, 2008). The redesigned statewide network of

MPAs reflects a large increase in area and habitats protected within

MPAs designed to enhance ecological connectivity. The investments in MPA planning have had other significant benefits for

marine management and stewardship in California by increasing

3

The California Marine Life Protection Act requires that the CDFG prepare

a master plan (CDFG, 2008) and that the Commission adopt regulations based on

that plan. The master plan is considered to be a draft, living document until the full

statewide MPA network has been adopted and integrated.

92

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

Table 1

The Marine Life Protection Act, enacted in 1999, has six goals which informed MPA design through the MLPA Initiative. The six goals emphasize ecosystem protection and also

address effective management of the statewide network.

Goal 1

Goal 2

Goal 3

Goal 4

Goal 5

Goal 6

To protect the natural diversity and abundance of marine life, and the structure, function, and integrity of marine ecosystems.

To help sustain, conserve, and protect marine life populations, including those of economic value, and rebuild those that are depleted.

To improve recreational, educational, and study opportunities provided by marine ecosystems that are subject to minimal human disturbance,

and to manage these uses in a manner consistent with protecting biodiversity.

To protect marine natural heritage, including protection of representative and unique marine life habitats in California waters for their intrinsic value.

To ensure that California’s MPAs have clearly defined objectives, effective management measures, and adequate enforcement, and are based on

sound scientific guidelines.

To ensure that the state’s MPAs are designed and managed, to the extent possible, as a network.

California Fish and Game Code Subsection 2853(b).

public awareness and forging lasting connections among stakeholders, scientists, and managers.

2.1. Increased protection of marine ecosystems and marine life

populations

The SAT developed scientific design guidelines for a network of

MPAs early in the planning processes. The MPA design guidelines

provided guidance on habitats to represent in MPAs, replication of

habitats in MPAs within a biogeographic region, and size and

spacing of MPAs to promote ecological connectivity (Carr et al.,

2010; Saarman et al., 2013). The SAT also developed a system for

classifying proposed MPAs in terms of the level of protection they

were likely to afford to the marine ecosystem within their boundaries, based on proposed allowed extractive activities, and evaluated which proposed MPAs were most likely to contribute toward

the ecological goals of the MLPA (Saarman et al., 2013). While

California’s MPA network was planned and is being implemented in

phases, one region at a time, an express statutory objective was to

design MPAs in each region to link together in an ecologically

connected statewide network.

With the completion of planning in four regions and implementation of MPAs along California’s open coast, there is a significant increase in the number of MPAs and area protected in state

waters compared to 1999 (pre-MLPA, Table 2). There are now (1)

more MPAs in state waters, (2) more area of state waters protected

in “no-take” areas, (3) larger MPAs that capture a broader range of

habitats (including many MPAs that extend from shore out to

deepwater habitats at the seaward boundary of state waters), (4)

more regular spacing among MPAs to promote ecological connectivity among marine life populations, and (5) clearer boundaries

and easier to understand regulations for all MPAs (Figs. 1 and 2;

more detailed regional maps available in online supplemental

information).

California’s open coast MPA network (including the 20 MPAs

adopted by the Commission for the North Coast region to be

implemented in early 2013), is comprised of 124 MPAs that cover

approximately 2196 km2 (848 mi2, Table 2). Of that total, approximately 1281 km2 (495 mi2) or 9.4% of state waters are in no-take

areas including 48 state marine reserves (SMRs), ten no-take

state marine conservation areas (SMCAs), and three State Marine

Recreational Management Areas (SMRMAs) that allow waterfowl

hunting but no other take of living marine resources. Approximately 373 km2 (144 mi2) or 2.7% of state waters is incorporated

into 17 MPAs that allow the take of some marine resources, while

still providing sufficient ecosystem protection to contribute toward

the ecological goals of the MLPA (Fig. 3). The remaining 46 MPAs in

the statewide network offer less protection to ecosystems and are

unlikely to contribute substantially to the ecological goals of the

MLPA due to the types of allowed fishing activities; however, these

MPAs are intended to contribute to the other goals such as

providing outreach and education, recreation, and research

opportunities, or protecting natural heritage.

The BRTF prioritized meeting the science guidelines to the

extent practicable. However, in each region other considerations

such as potential socioeconomic impacts, boater safety and feasibility concerns competed with the science guidelines and, in some

instances, the science guidelines were not fully met. Ultimately,

final MPAs implemented in the four regions differed in the

proportional area and extent of protection they provide. Nonetheless, a core set of MPAs are of at least the minimum recommended

size, sufficiently protective to contribute toward the ecological

goals of the MLPA,4 represent and replicate most habitats in each

region, and will likely be ecologically connected to other MPAs up

and down the coast (Table 3; Saarman et al., 2013). Statewide, more

than 20% of available rocky habitats are included in MPAs, while

soft-bottom habitats are represented at 14e19% of available habitat

(Table 3). To improve the ecological connectivity within the

network, habitats were replicated in MPAs within a region and

MPAs were spaced to enhance population connectivity for key

species (Saarman et al., 2013).

The goals of the MLPA largely focus on ecosystem and habitat

protection and not fisheries management; however, Goal 2 refers to

rebuilding depleted marine life populations including those of

economic value (Table 1). Possible fishery benefits (and impacts)

were an important part of the dialog among stakeholders

throughout the planning processes and many of the MPAs were

designed, in part, to protect and rebuild depleted stocks (Fox et al.,

2013c). It is anticipated that at least some MPAs in California’s

network will play a role in enhancing productivity and recovery of

fished populations, as well as providing a buffer against uncertainty

in fishery management strategies and models.

The potential benefits of proposed MPAs on fisheries was

assessed in three of the four planning regions using bioeconomic

models to predict potential changes in biomass and catch of

selected species resulting from spillover of larvae from MPAs into

fished areas (White et al., 2013). Some species, such as rockfish

(Sebastes spp.), are very slow growing and it will likely take years to

see any fishery benefits. Preliminary reports from the no-take SMRs

established in the Channel Islands in 2003 show signs of benefits to

some targeted species, particularly to shorter-lived species such as

California spiny lobster (Hamilton et al., 2010). The CDFG is identifying ways in which the MPAs could be integrated with fisheries

management under the State’s fisheries management law, the

Marine Life Management Act (Wertz et al., 2011). Understanding

how the network of MPAs may be contributing to fisheries

productivity will take time but could ultimately inform stock

assessments, harvest control rules, and other fisheries

4

The BRTF determined that MPAs of a “moderate-high” or higher level of

protection would likely contribute to the ecological goals of the MLPA (Saarman et al.,

2013).

93

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

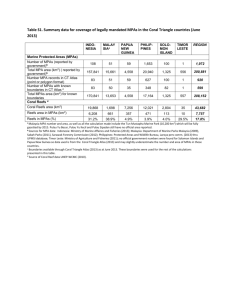

Table 2

Increases in the number of MPAs, as well as the proportion of state waters within MPAs, in California since the MLPA was enacted in 1999; planning and designation of MPAs in

the Channel Islands resulted in some increases in south coast protection before the start of the MLPA Initiative in 2004.

Study region

North Coast

North Central Coast

Central Coast

South Coast

Total

Area of MPAsa

Number of MPAs

No-take areasd

Total MPAs

No-take areasd

Total MPAs

No-take areasd

Total MPAs

No-take areasd

Total MPAs

No-take areasd

Total MPAs

1999

2004b

2012c

1999

2004b

2012c

1

5

1

14

5

12

3

32

10

63

1

5

1

14

5

12

15

43

22

74

6

20

13

25

13

29

29

50

61

124

5 km2 (0.2%)

8 km2 (0.3%)

<1 km2 (<0.1%)

70 km2 (3.5%)

19 km2 (0.7%)

106 km2 (3.6%)

6 km2 (0.1%)

183 km2 (3.0%)

31 km (0.2%)

368 km2 (2.7%)

5 km2 (0.2%)

8 km2 (0.3%)

<1 km2 (<0.1%)

70 km2 (3.5%)

19 km2 (0.7%)

106 km2 (3.6%)

417 km2 (6.9%)

471 km2 (7.7%)

442 km2 (3.2%)

655 km2 (4.8%)

133 km2 (5.0%)

355 km2 (13.3%)

219 km2 (11.1%)

394 km2 (20.0%)

218 km2 (7.4%)

529 km2 (17.9%)

711 km2 (11.7%)

919 km2 (15.1%)

1281 km2 (9.4%)

2197 km2 (16.0%)

a

Numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of state waters within each study region, or the percentage of state waters statewide (excluding San Francisco Bay) for

the total.

b

2004 calculations include MPAs established through the Channel Islands Marine Reserves process, which created 13 MPAs totaling 435 km2 around these Southern

Californian islands after passage of the MLPA, but before the start of the MLPA Initiative in 2004.

c

2012 numbers include MPAs adopted for the North Coast Study Region by the by the California Fish and Game Commission, which are anticipated to be implemented in

early 2013; MPAs in the other regions have already been implemented.

d

No-take areas include state marine reserves (SMRs), no-take state marine conservation areas (SMCAs), and those state marine recreational management areas (SMRMAs)

that allow waterfowl hunting, but no take of living marine resources.

management decisions at the state and federal levels (Field et al.,

2006; Wilson et al., 2010; McGilliard et al., 2011; Babcock and

MacCall, 2011; Fox et al., 2013c).

2.2. Advances in decision support for marine spatial planning

In addition to the advances in MPA science reflected in the

science design guidelines and involvement of scientists in the

Fig. 1. Prior to enactment of the MLPA in 1999, California’s had 63 MPAs covering less

than 3% of state waters; in 2003, 13 MPAs were implemented in the Channel Islands

following a separate MPA planning process.

process (Saarman et al., 2013), the Initiative also fostered advances

in decision support that will ultimately inform other coastal and

marine spatial planning efforts. The MLPA was a driving force to

compile existing and collect new marine spatial data (e.g., habitat

distribution, fisheries information, etc.) for California into

a centralized geodatabase (Gleason et al., 2010). Stakeholders were

empowered in their task of developing MPA proposals by

Fig. 2. The newly redesigned statewide network of MPAs includes 124 MPAs

protecting 16% of state waters, including 61 no-take areas that cover 9.4% of state

waters. Note, the 20 MPAs in the North Coast region are adopted and due to be

implemented in early 2013; all other MPAs in the state have been implemented.

94

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

Fig. 3. Regional and statewide summary of percentage area in MPAs of different types

and their associated level of protection. Notes: 1) see Saarman et al. (2013) for more

details on level of protection, 2) North Coast MPAs adopted and due to be implemented

in early 2013.

integrating the best readily available science with local knowledge

in a spatially-explicit context. The Initiative placed a strong

emphasis on collecting and utilizing local knowledge to inform

MPA design, with particular focus on mapping fisheries knowledge

(Scholz et al., 2004; White et al., 2013), non-consumptive uses

(NOAA, 2011; NOAA and MCBI, 2007), and tribal uses (unpublished

for confidentiality reasons). Finally, these data were made available

through the development of an online decision support tool,

MarineMap, used by stakeholders, scientists, and decision-makers

in the design and evaluation of MPA proposals (Merrifield et al.,

2013).

2.3. Increased capacity and involvement of stakeholders and

scientists

Through their engagement in MPA planning, many stakeholders

of widely divergent constituencies gained an increased understanding of California’s marine resources and the role of MPAs in

marine management. Stakeholders also gained valuable experience

in understanding the diversity of views on MPAs, and in working

with others toward negotiated solutions. By virtue of going through

a long, intense process together, stakeholders developed bonds that

helped to resolve some of the most difficult planning challenges

and may also help to bridge gaps between viewpoints in other

marine resource issues in the future (Fox et al., 2013c).

Similarly, scientists involved in the processes gained valuable

experience in making their scientific knowledge relevant to

decision-making and effectively communicating science to diverse

audiences (Grorud-Colvert et al., 2010). The Initiative utilized the

extensive scientific capacity in the state and engaged scientists as

both advisors and stakeholders. Many of the scientists participated

in more than one regional process and their command of the issues

and science communication skills improved significantly over time

(Saarman et al., 2013).

2.4. Increased coordination among agencies and with tribal

interests

The Initiative was designed to include participation from state,

federal and local government agencies, while maintaining

a commitment to implement the MLPA and to satisfy the timelines

and work products specified in the MOUs. As many state and

federal agencies have joint or overlapping jurisdiction in state

waters, but distinct mandates, there is an inherent risk that new

regulatory programs and policies may be in conflict with existing

programs if developed in isolation. These conflicts were addressed

through active consultation and coordination with other agencies

through all stages of the MPA planning processes. The goal was to

improve the compatibility of proposed MPAs with other existing

policies or programs, while achieving the goals of the MLPA.

Establishing formalized roles for agency staff within the regional

planning processes provided constructive mechanisms for agencies

to participate and express support or concerns (Fox et al., 2013b).

Additionally, as needed, ad-hoc interagency work groups were

convened to pursue policy or legal guidance on issues of emerging

importance that had not been previously explored or definitively

resolved (Fox et al., 2013c).

At the state level and prior to the Initiative, California Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) had developed plans for

underwater state marine parks that would be sited adjacent to

existing State Parks lands. Rather than adopt these plans, State

Parks worked with the Initiative to build upon the broad stakeholder involvement in the MLPA to identify, prioritize and leverage

funding sources for areas with the highest benefit under both the

MLPA and State Parks programs. Similarly, the federal Gulf of the

Farallones National Marine Sanctuary (GFNMS) had objectives for

enhanced seabird protection in the North Central Coast that were

met through the Initiative by involving regional stakeholders in the

design of special closures for protection of seabird colonies within

the MPA network5 (Fox et al., 2013c).

The MPA planning processes also gave many California tribes

and tribal communities a platform, especially in the North Coast, to

work together to represent their common interests and foster

greater dialog regarding tribal uses of marine resources within state

waters. Many viewed the MLPA as an opportunity for the State to

work with California tribes and tribal communities to preserve

their culture by accommodating traditional tribal uses of marine

resources within the MPA proposals and promote potential comanagement opportunities. Early on it became apparent that

neither a legal framework nor adequate communication mechanisms existed between California tribes and CDFG to meet the

expectations and interests of the tribes within the Initiative

process. While resolution of these issues was outside the scope of

the MLPA, the MPA planning process created political momentum

to pursue more robust communication among state and tribal

entities and to accommodate tribal uses of marine resources (Fox

et al., 2013c).

3. What were the costs?

The four regional MPA planning processes and the development

of a draft master plan for MPAs took nearly seven years and

significant financial investment and human capacity. An aggressive

timeline helped keep the regional processes on track, but required

dedicated staffing to maintain momentum and ensure transparency. Consistent with policy processes requiring important

changes in human behaviors and uses of natural resources, the

Initiative was controversial at times and confronted a variety of

political and legal challenges. Not all constituencies were satisfied

with the process or the outcomes.

3.1. Resources and time required

The Initiative proceeded at a fast pace with deadlines mandated

in the publiceprivate partnership MOUs to complete the statewide

draft master plan and four open coast regional planning processes

5

Special closures are geographically specific areas, generally smaller in size than

MPAs but compatible in purpose, designed and adopted by the Commission to

protect breeding seabird and marine mammal populations from human

disturbance.

95

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

Table 3

Regional and statewide summary of habitat representation, expressed as a percentage of mapped regional habitat availability, for key habitats in California state waters. Note

that the accuracy of habitat maps varies from region to region, with the most comprehensive habitat maps available in the North and North Central Coast regions.

Habitat types

Rocky shores

Kelp

Shallow rock (<30 m)

Mid-depth rock (30-100 m)

Deep rock (>100 m)

Beaches

Shallow sand (<30 m)

Mid-depth sand (30-100 m)

Deep sand (>100 m)

Estuary

Marsh

Eelgrass sites

Mapped eelgrass area

Tidal flats

North Coasta

North Central Coast

Central Coast

South Coasta

Statewide

No-take

Areasb

All MPAs

No-take

Areasb

All MPAs

No-take

Areasb

All MPAs

No-take

Areasb

All MPAs

No-take

Areasb

All MPAs

7.9%

5.0%

4.0%

20.6%

35.4%

1.4%

2.8%

6.8%

7.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

16.0%

8.4%

7.9%

22.2%

37.9%

11.3%

11.8%

15.0%

17.6%

2.7%

3.2%

37.5%

3.3%

1.0%

17.5%

15.4%

22.3%

17.1%

N/A

9.4%

4.0%

13.6%

0.0%

9.8%

17.9%

50.0%

23.7%

26.2%

32.0%

39.4%

36.5%

33.3%

N/A

11.2%

6.1%

24.5%

70.0%

22.7%

32.4%

50.0%

62.6%

34.2%

22.1%

27.7%

19.9%

11.5%

0.1%

15.8%

14.5%

4.3%

4.9%

22.9%

54.5%

100.0%

3.7%

42.1%

28.5%

44.1%

28.8%

26.5%

19.9%

21.5%

18.8%

11.4%

13.3%

54.5%

100.0%

100.0%

100.0%

69.3%

16.9%

9.4%

11.5%

18.7%

24.1%

7.1%

9.9%

14.5%

13.6%

4.3%

16.5%

14.3%

4.0%

2.0%

24.2%

13.2%

16.9%

21.2%

25.4%

12.9%

16.6%

18.7%

20.1%

7.8%

30.0%

14.3%

4.0%

20.1%

16.6%

13.3%

14.1%

16.9%

4.9%

8.4%

8.7%

9.9%

10.5%

5.2%

18.1%

23.8%

8.8%

11.1%

24.3%

21.9%

21.7%

26.3%

21.2%

14.5%

14.8%

17.1%

18.5%

12.3%

34.0%

38.1%

28.0%

21.1%

a

North Coast and Statewide numbers include habitat in MPAs adopted for the North Coast Region by the California Fish and Game Commission, which are anticipated to be

implemented in early 2013; MPAs in the other regions have already been implemented.

b

No take areas include state marine reserves (SMRs), no-take state marine conservation areas (SMCAs), and those state marine recreational management areas (SMRMAs)

that allow waterfowl hunting, but no take of living marine resources.

between 2004 and 2011. The completion of planning within one

region generally overlapped with commencement of planning for

the next region. Contributions from private charitable foundations

helped to support the intensive pace of the process by funding

Initiative staff who worked alongside CDFG staff.

The Resources Legacy Fund Foundation (RLFF)6 served as the

fiscal administrator for combined private charitable foundation

funding. Pursuant to the Initiative MOUs, the BRTF oversaw

expenditure of the funds to fulfill the goals and milestones set out

in the MOUs. The Initiative’s Executive Director managed the daily

operations of the Initiative, including expenditure of funds which

were used primarily for contract staff, partial support of CDFG staff,

public meetings, outreach, decision-support tool development, and

targeted studies to support the planning processes. The number of

contract staff employed by the Initiative during each of the regional

planning processes ranged from 8 to 14 and included project

managers, planners, scientists, facilitators, GIS analysts, outreach,

and policy experts. The private charitable foundation funding

contributions were made in three phases, as successive MOUs were

signed and budgets developed for each region. In total, approximately $19.5 million in private charitable foundation funds supported the development of the draft master plan, four regional MPA

planning processes, and environmental review of MPAs prior to

implementation.

Public funding for MLPA provided through the CDFG hinged on

annual funding allocations from the State Legislature. During the

pilot Central Coast process from 2004 to 2006, when state funds

were not made available, private funds supported participation by

five CDFG staff members. In 2006, the Legislature provided public

funds for existing CDFG staff participating in the Initiative. This was

followed by a substantial increase in state support for the Initiative

and MLPA implementation in general, with annual funding

augmented to approximately $4.4 million annually between 2007

and 2011. This increased public funding enabled CDFG to increase

core staff to around 13 for engagement in all aspects (planning,

technical, legal, policy, etc.) of the regional MPA planning processes.

It additionally provided for other positions devoted to other MLPA-

6

Resources Legacy Fund Foundation was a signatory to the memorandum of

understanding (MOU) creating the MLPA Initiative; it received funds from private

charitable foundations to support the Initiative process (www.resourceslegacyfund.

org/rlff.html).

related tasks (e.g., communications, public outreach, web design

and maintenance, research, and implementation). CDFG staffing

ranged to upwards of 35 staff at times for planning and implementation across multiple regions. In total, the State contributed

approximately $18.5 million during the nearly seven year planning

process.

As the primary implementing and managing agency, CDFG had

the added responsibility of fulfilling regulatory and environmental

review obligations immediately following the MPA planning phase

in each region. While Initiative contract staff were able to largely

redirect their focus to the next region, CDFG staff were faced with

simultaneously performing implementation responsibilities for

each region (e.g., rulemaking, developing and implementing

scientific monitoring programs, public outreach and education,

signage, and partnership development).

Other state, federal and non-governmental organizations also

contributed resources (e.g., personnel, facilities) and funds to

complete the Initiative process. For example, the California Ocean

Protection Council provided bond funds for statewide seafloor

mapping that, while not done for the sole purpose of MPA planning,

contributed greatly to the pool of “best readily available science”.

Several federal, state and local agencies provided staff to participate

in each regional planning process or provided direct technical

support. Many academic institutions allowed their faculty to

participate and volunteer on the SAT, other science endeavors

connected to the Initiative, and on the BRTF. Many nongovernmental organizations also provided staff to participate in

the planning processes as stakeholders or advisors. Individual

volunteers made significant investments of time in support of the

Initiative process by participating in the volunteer bodies (BRTF,

SAT, RSG); individuals within those groups each contributed

hundreds of hours at formal meetings and between meetings, the

vast majority without compensation for their time (Table 4).

3.2. Potential fisheries impacts

There was a concerted effort to incorporate local fishermen’s

knowledge into each regional MPA planning process to try to

reduce socioeconomic impacts to fisheries. This was accomplished

through surveys with local fishermen to identify areas of importance to different fisheries in California (Scholz et al., 2004; White

96

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

Table 4

A large number of people dedicated hundreds of volunteer hours to the MLPA Initiative public planning process, as formal participants on MLPA Initiative volunteer bodies and

by providing comments during public meetings. The public at large also provided thousands of written comments on prospective MPA designs, as well as other aspects of the

process.

Participation in volunteer groups

Over 3200 meeting days were contributed by approximately 200 RSG members.

Over 1000 meeting days were contributed by approximately 60 members of the SAT.

Over 400 meeting days were contributed by 14 different BRTF members.

These meetings amounted to nearly 38,000 total hours contributed by volunteers of the MLPA Initiative groups listed above.

General public participation

Nearly 4000 members of the public participated in workshops, open houses, and comment periods at public meetings. Hundreds more participated in field trips, public

mixers, and small group discussions.

Over 20,000 public comments were received in writing during the planning processes; over 50,000 comments received during environmental review.

et al., 2013) and dialog among individual stakeholders and with

decision-makers within the regional MPA planning processes.

While the MLPA does not require socioeconomic impact analyses, the scientific evaluation of each MPA proposal in each region

included a static estimate of maximum potential fisheries impact.

While these estimates assumed no spillover of fish from MPAs or

reallocation of fishing effort lost from proposed MPAs to other

areas, they did allow for an effective comparison of relative impact

among proposals (Scholz et al., 2004, 2012; White et al., 2013).

From this assessment, the potential maximum economic impact (in

stated importance, landings or dollar-value) was calculated for each

fishery and port group and provided to stakeholders and decisionmakers to help them evaluate and refine the MPA proposals to be

consistent with the goals of the MLPA and science guidelines, while

considering economic impact. The estimated maximum potential

impact on fisheries (expressed as a percentage of loss in net

economic revenue at the dock per year) from the MPAs ranged

widely by fishery and port group (1e29%), with a weighted average

ranging from 3 to 11% by region (Fig. 4). These estimates are

maximum potential values and are not expected to be realized due

to redirection of some of this fishing effort to other areas outside

MPAs, as well as potential benefits of MPAs on overall fishery

productivity; additionally, it should be noted that any real

economic impacts experienced by California’s ports and some

individual fishermen have not been quantified. Evaluations of MPA

proposals also included an evaluation of potential fisheries impacts

using bioeconomic models that considered potential spillover from

successful MPAs and management status of fisheries outside MPAs

(White et al., 2013).

3.3. Socio-political costs and challenges

While there were extensive efforts to engage a broad range of

interest groups and to foster cross-interest group dialog, at the end

of each regional planning process there were stakeholders who

were dissatisfied with the outcome. Some segments of this group

were vocally opposed to MPAs in general, and the publiceprivate

MLPA Initiative in particular, and were unlikely to support any

outcome that resulted in any new or revised MPAs in California. The

Initiative provided these interest groups with a very public platform for sharing their viewpoints. The Initiative and CDFG also

became a target for lawsuits and extensive public records act

requests that seemed to be aimed at stopping or slowing the

planning and implementation process (Fox et al., 2013a). While the

lawsuits to date have been unsuccessful in stopping MLPA implementation, they did distract from the planning processes and

required significant staff time and resources to adequately respond,

and thus are one of the ongoing “costs” of the process.

Some recreational and commercial fishermen, fishing organizations, and fishing-related business interests were and still are

opposed to MLPA implementation. Many fishermen view new or

revised MPAs as unnecessary area closures for fisheries already

heavily regulated; many of these fishermen had already experienced economic declines or reduced landings due to increasingly

restrictive regulations and/or declining stocks. From that perspective, the ecosystem protection goals of MLPA are difficult to separate from fisheries management when one impact of MPAs is to

limit fishing opportunities. Others maintain that it is impractical for

California to manage and enforce additional MPAs given the fiscal

crisis currently facing the State, despite commitments from many

city, county, state and federal enforcement agencies to partner in

these efforts. An important challenge to managing MPAs in the long

term will be to address these issues by providing insights into the

role of MPAs in rebuilding or sustaining fished populations and the

role of fisheries management in complementing or enhancing MPA

benefits to fisheries.

Another segment of stakeholders were supportive of the MLPA

and participated actively in the processes (as part of the RSG or

general public), but were ultimately disappointed by the

outcomes (either specific MPAs or the set of MPAs) of each

regional process. Many of these individuals had strong desires for

specific outcomes (e.g., specific geographies being included or not

included as MPAs; specific activities being allowed or disallowed

in MPAs; etc.) that were not included in the final decisions. The

final recommendations made by the BRTF and decisions made by

the Commission in each region reflected a compromise among

divergent interests and therefore did not fully satisfy many

different constituencies, including some conservation and fishing

interests.

4. Some key lessons learned

Fig. 4. Regional summary of maximum potential commercial fisheries impacts in each

region for the preferred alternative MPAs submitted to the Commission, based on

surveys of fishermen and assuming no shift in fishing effort outside of MPAs

(Scholz et al., 2012).

There were many lessons from the MLPA Initiative that can

inform other resource planning efforts; five of the most important

are described here.

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

4.1. The importance of enabling conditions in place upfront

Political support for the MLPA at the highest levels of government was needed to keep the process moving forward over many

years, despite legal and political challenges (Fox et al., 2013b). The

statewide planning process could not have been successfully

completed without the legislative mandate of the MLPA, with its

explicit goals and requirement to establish a statewide network of

MPAs. The Initiative was a policy implementation process that did

not get bogged down by debates on the merits of MPAs, as the

Legislature had already determined that a statewide network of

MPAs was needed. Moreover, the definitions of types of MPAs

provided in the Marine Managed Areas Improvement Act and the

legal authority provided in Fish and Game Code sections 1590 and

1591 (all enacted concurrently but separately in 2000) proved

important as the legal basis on which the Commission actually

designated MPAs after each regional planning process (Kirlin et al.,

2013).

As a publiceprivate partnership, the Initiative provided the

necessary funding and capacity, within the context of a specific

mandate and timeframe, to help a state agency meet its statutory

requirements. Adequate funds allowed the Initiative to overcome

many of the shortfalls in capacity that hindered the prior unsuccessful attempts to implement the MLPA. Pairing CDFG staff, with

their scientific expertise and knowledge of state policy and

resource management, with professional contract staff with other

required skills (e.g., MPA planning, project management, decision

support tool development, facilitation and mediation), created the

right capacity to deliver outcomes that were implementable. The

private charitable foundation funds proved to be more flexible than

state funds, enabling the Initiative to be nimble and responsive to

the needs of the process and fluctuations in state budgets and

staffing. The private funds were also used to bolster the best readily

available data, when necessary, through focused efforts (e.g.,

mapping areas of importance for fisheries) and to enhance public

outreach capacity and actions (e.g., in the populous and diverse

South Coast region).

4.2. Appropriately scaled and phased approach to planning

The statewide network was designed through four regional and

consecutive planning processes that began with a Central Coast

pilot region to test and refine the approach. This phased approach

allowed for planning on more appropriate spatial and temporal

scales and overcame some of the challenges of the prior statewide

efforts that were unsuccessful in part due to the size and

complexity of California’s coast.

In addition to being more manageable in size, the four regions

also reflected more cohesive units in terms of biogeographic

patterns and sociopolitical factors (e.g., dominant regional industries, social connectedness of resident populations within regions,

reasonable driving distances to meetings, presence of relevant

regional institutions). A regional approach facilitated integration of

the best readily available science and policy guidance into the

process, as guidelines could be adapted based on regional conditions, and local scientific experts could be engaged (Saarman et al.,

2013; Fox et al., 2013c). A regional approach also allowed time for

technical planning tools, as well as facilitation and outreach techniques, to evolve over the course of the process (Merrifield et al.,

2013; White et al., 2013; Sayce et al., 2013). The short timeline in

the first pilot region (7 months) demonstrated that the time allocated for a regional process needed to be increased (to 12e14

months per region for the remaining regions).

Dividing California into regions may have lengthened the overall

timeline for completing planning of the statewide MPA network.

97

However, the phased approach yielded positive outcomes for each

successive region, as the Initiative team tested and learned which

process design and outreach approaches were more likely to be

effective. Moreover, building an MPA network region-by-region

allowed for recognition of regional differences in stakeholder

desires, physical realities (e.g., natural hazards and differences in

boater safety conditions that limit human access to ocean

resources), and status of marine resources to drive substantive

outcomes (number and type of MPAs established as well as

percentage of state waters covered by MPAs).

4.3. Adaptively managed process design with clear roles and

outcomes

The use of three separate volunteer groups (i.e., the RSG, SAT,

and BRTF), each with clear and distinct roles and supported by

Initiative staff, helped drive MPA planning forward in an organized

manner. The stakeholders participating in each region’s RSG were

empowered with the responsibility for crafting MPA proposal

alternatives, leveraging the knowledge of those arguably most

affected by redesigned MPAs (Fox et al., 2013b). The RSG members

also served as vital links to the broader public (Sayce et al., 2013).

Scientists serving on the SAT for each region ensured that the

stakeholder MPA designs were informed by scientific guidelines,

provided ecological and socioeconomic evaluations at key points in

the process, and answered scientific questions on an ongoing basis

(Saarman et al., 2013). The BRTF provided oversight, addressed

difficult policy issues, and served as a buffer between the stakeholders and political forces by recommending a preferred alternative of MPAs to the Commission for each region (Kirlin et al., 2013).

Not requiring stakeholders to reach consensus on a single

proposal for MPAs, but encouraging them to develop a range of

alternative MPA proposals was also key to successfully completing

the regional MPA planning processes. This approach meant that

most stakeholders had at least one MPA proposal they could

support, and gave the decision-makers the ability to evaluate

tradeoffs and make compromises in their decision-making process,

thereby garnering more broad-based acceptance of the MPAs being

implemented. In three regions, the stakeholders developed

multiple alternative proposals; however, in the North Coast region,

the stakeholders did reach consensus on one proposal (Fox et al.,

this issue-b).

The Initiative’s investment in explicit “lessons learned” evaluations after planning in each region was completed was an important component of the adaptive planning process design that

helped inform the process design for subsequent regions (Gleason

et al., 2010; Fox et al., 2013b).

4.4. Ensuring transparency and mechanisms to navigate

controversy

MPA planning and implementation in California was, and still is,

controversial among certain sectors, particularly recreational and

commercial fishing interests, and within tribal communities.

Members of the public were intensely interested in the planning

process and meetings were heavily attended, which helped create

the need for a formal public outreach strategy (Sayce et al., 2013).

Some issues became so controversial, such as potential impacts to

traditional tribal gathering, that they had to be addressed through

extra meetings, adjusted meeting formats, and parallel consultation between and among tribal representatives, SAT members and

affiliated researchers, state agency representatives, RSG members,

and BRTF members. Some entities, particularly recreational fishing

organizations, consistently criticized the process and worked to

98

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

impede its progress through lawsuits and media campaigns (Fox

et al., 2013a).

The Initiative used several strategies and structural arrangements to help participants navigate controversies and policy issues.

One effective strategy was structuring the role of the BRTF to

publicly navigate issues and tradeoffs and make recommendations

to the decision-makers. The BRTF was able to publicly air issues and

develop specific recommendations on policy questions and

controversial decisions; this approach provided an important filter

for issues before final decisions on MPAs were made in each region

by the Commission.

The Initiative also made significant investments to make the

process as transparent as possible and widely accessible to the

public through online tools, webcasts of meetings, online documents, public outreach workshops, media broadcasts, and other

mechanisms (Merrifield et al., 2013; Sayce et al., 2013). Although

these efforts were designed to create process transparency, they did

not assuage the most vocal opponents of the Initiative. Intense

scrutiny and controversy created challenges for the Initiative staff

to effectively conduct meetings: public comment periods often

extended for many hours (Sayce et al., 2013); and some stakeholders engaged in strategic gaming during RSG meetings (Fox

et al., 2013b). Public scrutiny also made delivery of the best available science difficult, as stakeholders lobbied for changes to design

guidelines and misunderstood the open discussion by scientists to

indicate lack of scientific rigor (Saarman et al., 2013). A flexible and

transparent process can be helpful for addressing political controversy in similar processes, but managers should not underestimate

the challenges and the resources required to address them.

4.5. Ensure timely delivery of best available science

The importance of delivering the best readily available science in

a timely manner and in a form that stakeholders and policy-makers

can understand cannot be underestimated. The Initiative made

a significant investment in compiling spatial data into an authoritative geodatabase and developing the tools to make those data

available for planning (e.g., MarineMap, see Merrifield et al., 2013).

This investment paid off by empowering the participants to take an

active role in designing and evaluating proposed MPAs against

design guidelines using a common set of underlying data. Similarly,

the effort made by the SAT to develop science-based design guidelines provided a common framework for comparing among

proposals in the iterative design process (Saarman et al., 2013).

At times the process moved so fast and the science support

needs were so great, that the SAT had difficulty keeping up with

timely delivery of science to Initiative participants. The SAT

responded by meeting more frequently than originally planned and

forming “working groups” to keep up with the scientific questions

and needs of the stakeholders and BRTF (Saarman et al., 2013).

More advance time to anticipate stakeholders’ questions and

science needs generally and to compile and analyze existing data

prior to the commencement of the planning process may have

helped to alleviate this issue.

The SAT was structured and charged to provide only scientific

advice to the other Initiative participants (including helping to

parse policy from scientific questions); such a clear non-advocacy

role enhanced its credibility. Importantly, the SAT was charged

with evaluating all alternative MPA proposals relative to the science

guidelines, rather than crafting MPA proposals. Building in time for

and training in science communication was also key to integrating

science effectively into RSG, BRTF, and Commission decision

making (Grorud-Colvert et al., 2010). Science was more successfully

integrated into the process when the SAT had time to research

a topic and clearly present findings to the other volunteer bodies

(see Saarman et al., 2013).

5. Challenges ahead for implementation, monitoring, and

adaptive management

California’s new network of MPAs needs to be enforced, monitored, and adaptively managed over time in order to deliver any of

the anticipated ecosystem and fishery benefits. If carefully

managed into the future, California’s network of MPAs will provide

a valuable testing ground for MPA design and the benefits MPAs can

provide. In the current and foreseeable fiscal climate in California,

however, finding the resources to follow through on the monitoring

and management will be challenging.

5.1. MPA implementation and long-term management

The publiceprivate partnership structure of the Initiative

provided CDFG with the additional capacity it needed for planning

the statewide MPA network; however, that partnership, as originally envisioned, did not extend to the implementation and

management stages. Recently the foundations that supported the

Initiative have committed additional support for various aspects of

MPA network implementation and management.

For planning, the Initiative paired contractors with specific skills

(e.g., meeting facilitation, process design, planning, and outreach)

with CDFG staff that could provide critical state policy context and

continuity, and led to outcomes that were implementable by the

State. Implementation and long-term management of the statewide MPA network will similarly require an innovative and adaptive approach to link state agencies with additional capacity and

skills to implement and sustain effective outreach and education,

monitoring, enforcement and other essential functions, particularly

given the scale of California’s coastline (1700 km) and magnitude of

the statewide program consisting of 124 MPAs.

The publiceprivate partnership model may offer a viable

mechanism to leverage other sources of funding to improve efficiencies in MPA implementation and management, particularly if

organizations beyond private charitable foundations can be

engaged. For example, in 2010, a MOU was signed by 10 government and non-government agencies to memorialize their

commitments to successful implementation of the statewide

network of MPAs (e.g., public outreach, monitoring and enforcement of MPAs).7 This “MLPA Implementation MOU” is a critical

starting point for building sustained commitment and efforts

through a network of agencies and other partner groups that may

have otherwise only had active engagement in the planning and

design phase or disparate and uncoordinated efforts to assist with

implementation. Collaborations of this nature may constitute

a major asset and factor in successfully moving beyond isolated

efforts to leverage the expertise and information-sharing from

other partners (Sievanen et al., 2011).

7

Signatories to January 2010 “Memorandum of Understanding for Implementation of the California Marine Life Protection Act” were the California Natural

Resources Secretary, California Ocean Protection Council (Secretary, Chair), California

Environmental Protection Agency (Secretary), California Department of Fish and

Game (Director), California Department of Parks and Recreation (Director), State

Water Resources Control Board (Executive Director), U.S. National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA Western Regional Team Lead), U.S. National Park

Service (Regional Director), U.S. Department of Defense (Commander of Navy

Southwest Region Environmental Coordinator), California Ocean Science Trust

(Chair, Board of Trustees), and Resources Legacy Fund Foundation (Executive

Director).

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

5.2. Monitoring to evaluate effectiveness of the MPA network

California is developing a long-term monitoring program and

funding model to meet the challenge of assessing the effectiveness

of the MPA network. The independent non-profit California Ocean

Science Trust established the MPA Monitoring Enterprise8 in 2007.

The MPA Monitoring Enterprise is an example of a new partnership

approach to monitoring California’s MPA network. The MPA Monitoring Enterprise provides dedicated and independent capacity to

work alongside CDFG and any other implementing agencies and

entities (e.g., State Parks, local jurisdictions, National Parks, NGOs,

academics, tribal communities) to develop the MPA monitoring

program. The MPA Monitoring Enterprise also provides an opportunity for both framing MPA monitoring approaches to the scale of

California’s MPA network and for providing information directly in

support of future MPA assessment and management decisions.

Key to measuring the effectiveness of the MPAs will be the

development and funding of a monitoring program that can track

indicators of importance to stakeholders, such as changes in size and

abundance of fish and other harvested resources. MPA monitoring

has tended to emphasize assessing differences in densities and sizes

of organisms inside and outside MPAs; however, that may be

insufficient to assess progress against broad ecosystem protection

goals, such as those of the MLPA. Therefore, the MPA Monitoring

Enterprise, in close collaboration with CDFG, has led development of

a monitoring framework that includes indicators to track trends in

ecosystem condition and evaluate the effectiveness of MPA design

and management decisions (MPA Monitoring Enterprise, 2010,

2011). This approach responds to the ecosystem-based policy

framework while pushing the limits of scientific knowledge, and

consequently will require testing and refinement over time.

Within the current state fiscal crisis, limited funding for monitoring has the potential to hamper the State’s ability to monitor the

effectiveness of the new MPAs. However, the California Ocean

Protection Council has committed funding ($16 million) for baseline monitoring in the MPAs. With this support, California is

establishing an ecological and socioeconomic benchmark against

which future MPA performance can be measured. Moreover, this

benchmark can inform other management dialogs on fisheries and

climate change, creating a window of opportunity to develop costeffective long-term monitoring and evaluation. Baseline monitoring programs have already been initiated in selected MPAs

within three of the four regions.

5.3. Adaptive management

The MLPA requires adaptive management9 to ensure that the

policy goals of the MLPA are being met. Adaptive management is

a systematic approach to improving policy success by learning from

experience and adjusting implementation efforts based on what

was learned (Walters, 1986; Lee, 1999; and many others). For the

MLPA, adaptive management includes monitoring and assessment

of MPAs, review of the network of MPAs and consideration of

relevant new scientific findings, followed by recommendations to

the Commission for any modification to the network of MPAs to

improve their performance in meeting MLPA goals. The Commission adopted a policy within the draft master plan, in which

regional components of the network of MPAs should be monitored

and reviewed every five years. This approach includes evaluating

8

www.monitoringenterprise.org

Section 2853(c)(3) of Fish and Game Code states that the management plan

must have “provisions for monitoring, research, and evaluation at selected sites to

facilitate adaptive management of MPAs”.

9

99

the efficacy of individual MPAs and the network, as well as,

reviewing the monitoring program(s), methods, and results and

making recommendations for management adjustments in a ‘test

and assess’ framework (CDFG, 2008; Day, 2008).

In addition to the five-year reviews, the Commission will support

MPA management by, at least every three years, receiving and

considering action on any petitions from the public or other interested entities to add, delete, or modify any MPAs. Though there is an

apparent disconnect between the timing of considering proposals to

alter MPAs every three years and the 5-year review period, beyond

the first three year period the structure allows sufficient time for

a comprehensive regional assessment to inform proposals to modify

the MPA network and for the Commission to request an assessment

of any proposed change against existing monitoring results. Upon

receiving a review of the MPA network and any proposals to modify,

add, or delete MPAs, the Commission may change MPAs to better

meet the goals of the MLPA or to address specific concerns (e.g.,

boating safety, enforcement feasibility, etc.).

It remains to be seen whether California’s MPA network, which

reflects significant tradeoffs between ecosystem protection and

socioeconomic considerations, will adequately meet the goals of

the MLPA. Given the life history traits (i.e., growth rate to maturity,

age at sexual maturity, life expectancy, and fecundity) of many

species now protected in these MPAs, it is anticipated that

measurable biological responses to the MPAs may take a decade or

more. Therefore, management adjustments should be made with

caution to allow sufficient time for the effectiveness of the MPAs to

be adequately assessed before adjustments are made.

6. Conclusions

The Initiative successfully completed four regional planning

processes and California is now implementing a statewide network

of MPAs. This is the most comprehensive MPA planning process to

date in the United States, and holds global significance (Toropova

et al., 2010). As such, the Initiative experience is particularly relevant to similar efforts to plan and implement MPAs in developed

countries, where governance structures and institutional capacity

levels are similar.

Although many years will be required to fully assess whether the

ecological goals of the MLPA will be achieved, many significant

achievements can already be enumerated. First, the overall statewide area within MPAs has been significantly increased from <3% to

16% of state waters, including over 9% in no-take areas, and will likely

benefit numerous ecosystems and a wide range of marine organisms, including some recreationally and commercially important

species. Most marine and estuarine habitats have been represented

and replicated within MPAs in each region. In each region, there is

a “backbone” of MPAs (often no-take areas) that will provide

substantial ecosystem protection. For many key habitats the spacing

between adjacent MPAs should promote ecological connectivity

between protected populations, although spacing guidelines were

not met consistently across all habitats statewide (Saarman et al.,

2013). All of California’s MPAs now have consistent classification,

were explicitly designed to meet regional objectives and MLPA goals,

and are intended to be administered as a statewide system.

The positive outcomes achieved for ecosystem protection help

to offset the significant time, energy, and financial resources

dedicated to the Initiative process. California’s MPA planning

process took much longer than anticipated by the Legislature,

required significant resources to complete, and continues to be

controversial within some sectors and communities. It has been

well over a decade since the State enacted MLPA and yet the original intent was to establish the statewide network within two years

of enacting the law. Successful completion of the planning effort

100

M. Gleason et al. / Ocean & Coastal Management 74 (2013) 90e101

was achieved only after two unsuccessful attempts, a redesign of

the process, and an investment of millions of dollars and thousands

of hours of staff and volunteer time (approximately $38 million in

public and private funds over a seven year period). However, when

calculated as the cost per square kilometer of protection (approximately $17,000), that cost is comparable, and in many cases less

than, the cost of establishing MPAs in other parts of the world

(McCrea-Strub et al., 2011).

While the Initiative set a high bar for transparent public

resource planning, and one that may be difficult to replicate elsewhere given generally available funding and capacity, the lessons

learned have relevance for other environmental planning efforts.

The MPAs designated by the Commission in each region aim to

satisfy the goals of the MLPA and meet the science and feasibility

guidelines to the extent possible, while addressing socioeconomic

impacts and garnering the broadest possible public acceptance. The

regional context differed markedly in each of the four open coast

regions and that regional variance challenged decision-makers. The

MPAs being implemented thus reflect neither a strictly scientifically

designed network nor simply the preferences of stakeholders, but

rather a network achieved through a public policy process that

integrated input from stakeholders and scientists and ultimately

reflects the best judgment of policy makers.

While balancing the MLPA goals of ecosystem protection with

potential socioeconomic impacts to fisheries was highly visible in

the Initiative process, many other issues and potential conflicts

between MPAs and other types of marine management or use areas

(e.g., military, tribal, wastewater discharge) also had to be addressed

or resolved through spatial planning or policy choices (Fox et al.,

2013c). Recognizing that many ocean use activities co-occur,

conflict with each other, and potentially negatively impact marine

ecosystems, there is increasing support among marine natural

resource managers to collaborate and foster partnerships that focus

on broader integration for ocean and coastal management.

As has been shown elsewhere, the importance of effective

management, enforcement, and monitoring once MPAs are established cannot be underestimated (Day, 2008). Governmental

agencies and collaborating entities responsible for both implementing MPA planning processes and managing MPAs into the

future face increasingly complex management responsibilities and

challenges. Given the costs of implementation and management,

strategically preparing agency staff through targeted capacitybuilding and identifying long-term roles and responsibilities with

community partners can help maintain a level of consistency and

continuity between the planning, regulatory, and implementation

phases. Strategic use of publiceprivate partnerships, collaborations

among organizations, and promotion of local stewardship and

co-management opportunities may help fill gaps in funding or

capacity going forward. In addition, managers, scientists, and

stakeholders who contribute individually meaningful and

collectively thousands of volunteer hours in the MPA planning

process have a stake in the long-term outcomes of their efforts and

may want to further engage in the monitoring and adaptive

management framework. The efforts made to encourage participation in and credibility of the MPA planning process should translate

to an MPA constituency over time, especially if the MPAs are shown

to provide long-term benefits to resources and people.

Ethical statement

The authors assert that the attached manuscript is an original

work, has not been published before, and has not been submitted

for publication elsewhere. All authors have substantively contributed to analysis and writing of this manuscript and have agreed to

submit the manuscript to Ocean & Coastal Management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who were involved in all aspects of

the Initiative planning effort for their input and contributions. Most

of the authors received direct or indirect support through RLFF

during the MLPA Initiative process. The authors who volunteered

their time to the Initiative thank their employers for supporting and

encouraging their commitment to the Initiative.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data, including regional-scale maps, related to

this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.

2012.08.013.

References

Agardy, T., Bridgewater, P., Crosby, M.P., Day, J., Dayton, P.K., Kenchington, R.,

Laffoley, D., McConney, P., Murray, P.A., Parks, J.E., Peau, L., 2003. Dangerous

targets? Unresolved issues and ideological clashes around marine protected

areas. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 13, 353e367.

Airame, S., Dugan, J.E., Lafferty, K.D., Leslie, H., McArdle, D.A., Warner, R.R., 2003.

Applying ecological criteria to marine reserve design: a case study from the

California Channel Islands. Ecological Applications 13 (1), S170eS184.

Babcock, E.A., MacCall, A.D., 2011. How useful is the ratio of fish density outside

versus inside no-take marine reserves as a metric for fishery management

control rules? Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 68 (2),

343e359.