L. Davis, Students Focus on What They Want, Loughborough

advertisement

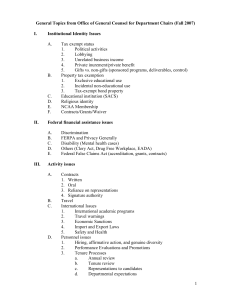

Students Focus on What They Want Lesley Davis LTSN Engineering, Loughborough University 1 ABSTRACT As part of the Needs Analysis for LTSN Engineering, three focus groups have been facilitated to provide a snap shot of student opinion on learning and teaching in engineering subjects. The three institutions visited were a campus university and two city universities, one post- and one pre-1992. The pre-1992 institution had a high proportion of local students from an ethnic minority group. Although there were some local differences, there were some comments that were repeated during all three sessions. This paper will report the results of the focus groups, identifying the common themes that were of importance to the students within their own learning experiences, including methods that helped them to learn. It is interesting to note that the students had fairly low expectations and identified easy to implement activities. 2 INTRODUCTION In September 2000, LTSN Engineering commenced a major consultation exercise to establish the issues that are of concern to the stakeholders in engineering education in the UK. The exercise consisted of interviews and workshops with academics, student focus groups and a widely distributed questionnaire based survey. This paper briefly reviews the consultation exercise and presents the main issues identified. It then goes on to describe the process that was used to consult a sample of the student population. The consultation of students consisted of facilitating three focus groups at three different institutions covering three engineering disciplines. 3 LTSN ENGINEERING The Learning and Teaching Support Network (LTSN), launched in January 2000, comprises of 24 subject centres, a Generic Centre and a programme director to manage and co-ordinate the network, based at the ILT at York. The Network was established following a review (1) of existing learning and teaching initiatives, which acknowledged that academics best appreciate, assimilate and implement a pedagogic approach when presented to them within their own discipline. It recommended establishing a subject-based support network with a broad focus across all learning and teaching activity. LTSN Engineering, hosted by Loughborough University, promotes quality learning and teaching within engineering disciplines by stimulating the sharing of good practice and innovation through the provision of subject-based support. The Centre’s three key aims are to: • co-ordinate and support learning and teaching in engineering disciplines in higher education. • create a national focus which is the point of contact for all involved in engineering disciplines in higher education. • collate and disseminate good practice and innovation in learning and teaching in engineering disciplines in higher education. 4 OVERVIEW OF CONSULTATION EXERCISE The consultation exercise was designed to enable all major stakeholders in engineering education to contribute their opinions but with the main thrust being on reaching engineering academics as it is to this group that LTSN Engineering is seeking to provide its prime services. To achieve the best results from a questionnaire survey, a pilot study was carried out to hone the format of the questionnaire. The pilot study consisted of telephone and face-to-face interviews with nominated contacts from fifteen engineering departments in the UK. These results were then used as the basis of two workshops held as part of the staff development programmes at two universities. A draft questionnaire was also produced and distributed at the IEE’s Engineering Education Symposium in January 2001. The findings from these activities were consistent and therefore LTSN Engineering felt confident that they had identified the issues that were of concern to engineering academics and designed the final questionnaire, which was widely distributed, to establish the relative importance placed on the issues by the different stakeholders. Academia Stakeholders Consulted Industry Professional Institutions, etc Interviews Students Focus Groups Workshops Pilot Study Questionnaire (Engineering Education Symposium, January 2001) Major survey (distributed through professional journals and departmental contacts) Figure 1 – Development of the methodology used in the consultation exercise The questionnaire was divided into five sections; Issues in Engineering Education, Priorities for the Work of LTSN Engineering, Services and Activities, Communication Methods and Expertise. The findings of the survey include demonstrating that the major concerns are centred on delivering an effective education to students with decreasing mathematical knowledge and motivation with fewer resources available. Academics demonstrated their desire to have readily accessible solutions to their current problems and their lack of interest in debate about the issues by prioritising identifying and sharing good practice and preferring email communication and the use of a website over journals and conferences. Industrialists wish to develop strong links with academia so that “suitable” graduates can be produced. (2) Although it was possible for students to complete a questionnaire, it was recognised that only a small number of students would receive a questionnaire (they were mainly distributed through the magazines of some of the professional institutions) and feel motivated to complete and return it (thirteen out of over 700 responses received were from students). LTSN Engineering recognises the importance of students as stakeholders in engineering education and therefore sought a simple and efficient method to gain a reliable impression of student opinion. The method selected was to conduct focus groups that would be held at a range of universities covering a range of subject disciplines. 5 THE FOCUS GROUPS The purpose of the focus groups was to canvass student opinion about the learning and teaching experiences in which they had participated. Final year students were chosen to make up the groups, as they would have several years experience of learning and teaching activities on which to reflect and would be well placed to understand their degree programmes in the context of trying to obtain employment. It has been shown that six focus groups are sufficient to generate approximately 90% of the potential ideas in a product development process (3). In this situation, where the groups are congruent and the subject of concern well understood by the participants, it was felt that a smaller number of groups covering a range of disciplines would be sufficient to explore the issues of concern to the student population. Three focus groups were convened and facilitated by the author, with the cooperation of a member of the academic staff within the department concerned. The students attending a single focus group were all drawn from the same academic department at a particular institution (see Table 1). At two of the institutions, the students were invited to discuss their experiences over a free lunch, however in the third case, the students were not informed prior to the event and the discussion took place at the start of a revision lecture (thus ensuring a high level of attendance!). Group A B C Table 1 – Description of the Focus Groups Type of Discipline Group Size Institution Campus, pre-1992 Manufacturing Engineering 3 (1 female) City, pre-1992 Chemical Engineering 7 (3 females) Industrial Information City, post-1992 11 (1 female) Technology Method of Invite Free Lunch Free Lunch Revision Lecture Groups A and B were predominantly white, middle class students but Group C had a significant ethnic mix with only one white student in the group. The proportion of female students was low, as would be expected in an engineering group; the higher proportion found in Group B, the Chemical Engineering students, reflects the national statistics for this discipline. The focus groups were conducted around a table so that the facilitator could maintain eye contact with everyone and that there was no overt hierarchy at play within the group. The discussions were taped and later transcribed for analysis, this enabled the facilitator to concentrate on keeping the discussion flowing rather than taking copious notes. The facilitator used a list of questions to stimulate discussion (see Table 2) and ensure that a common set of issues would be addressed by all of the groups. The conversation was allowed to deviate from the prescribed list when it contributed to fulfilling the aim of the focus groups and the order of questioning was not strictly followed to prevent abrupt changes of direction. Table 2 – Questions used during the focus groups 1 What is the best thing about your course? 2 Which teaching methods work best for you? 3 Which assessment methods do you prefer? 4 Do you think your maths skills are sufficient for your course? 5 Do you think your maths skills are sufficient for your proposed career? 6 What skills do you think you have developed during your course? 7 Are there any skills that you would like to develop further? 8 Are you a member of any of the professional engineering institutions? 9 Do you aim to achieve CEng? 10 Will you do any further study? The sessions with each group lasted for approximately one hour each although Group C (the opportunity sample from the revision lecture) was a little shorter which may be due to them not being pre-warned about the discussion and therefore not having the opportunity to consider the subject before the session. 6 FINDINGS FROM THE FOCUS GROUPS The findings from the focus groups are discussed under six headings, which correlate with the questions from Table 2. Quotes (shown in italics) are taken from the transcript when they illustrate the points made. 6.1 Course highlights The students enjoyed the variety of topics they covered in their courses and mentioned design projects, which exploited any of the skills and knowledge that they had acquired. They were also keen on any industrial contacts to which they were exposed, including from guest lecturers, sitevisits and placements. They unanimously felt that this industrial contact was essential to developing their understanding of and maintaining their interest in their courses. 6.2 Teaching experiences and lecturers The students felt that they needed plenty of opportunity for practical applications of the theory being presented. They wanted to be able to practice applying what they were told in a lecture theatre to “real-life” examples and wanted the material placed in an industrial context. “I find I need to apply what I learn in examples otherwise I just don’t take it in or if you can’t see how it’s related to being a chemical engineer.” “If you’ve got examples it focuses your mind more and you want to do it. If you just get loads of notes then you’re not going to look at then.” “Make it more relevant so it’s not just a random bit of theory. Say why you are being taught it and why it would be useful to you.” On the subject of the lecture, the students felt that lecturers often overestimated their knowledge and abilities when preparing their material. They felt that lecturers should talk to them and try and interact with them rather than simply talk at them. Having a sense of humour and being prepared to have some fun was seen as an asset for any lecturer. They wanted clear supporting handouts that they could find their way around easily. They felt that lecturers should respect them enough to be organised for the lecture and also not to see students as an inconvenience, which got in the way of their research activities. “Their expectations are high and when they give you lectures, some of the basics they think you know already, you might not know.” “If they pitched it a little simpler you would learn it instead of sitting there, thinking I will never know this.” “I think what they did at A-levels and what we did at A-levels has changed a lot. They always think ‘you should have done this at GCSE’.” “Her lectures are always much more fun. She does involve us, she does get a lot of examples, and people out on the front and stuff.” “Hand-outs should have bullet points and be self-explanatory and you can read through, straight to the point.” “If a lecturer makes you feel like we’re not getting in their way then that will make a huge difference.” 6.3 Assessment There was a mixed view on the preferred mode of assessment. Some students preferred exams but others preferred coursework and groupwork. The message coming through was that a mixture of methods should be used to ensure that all students could have an opportunity to excel. “I prefer exams because I can’t be bothered to do all the reading.” “I find I’ve learnt more doing coursework than when I have exams. Exams are just regurgitation.” “Group assessment is evil. I can see its worth definitely, but it causes so much argument.” 6.4 Mathematical Skills Most of the students felt that they were taught mathematics at too high a level and it was divorced from the applications where it might be useful. They felt that they came to university with such a variety of knowledge and skill in maths that the university should identify those that needed help early on and provide them with extra tutorials from the start. They also felt that extensive mathematics classes were not necessary as once they got into industry they could always look up any mathematics when and if they needed it. “They teach you all this algebra but you hardly ever use it.” “You get taught it in your first and second year when you don’t need to use it. By the time you get to your third year when you need it you’ve forgotten it all so we may as well have not bothered.” 6.5 Transferable Skills The students did feel that there were plenty of opportunities to develop their presentation, group working and computer skills. Some felt that there should be specific teaching of these skills, or at least some consistent indication from lecturers about what was expected, but others felt that they would receive that type of training duirng their graduate training from their employers. They did feel that these skills were important and would make them more employable. “You need people with life skills. I know people who will get a first but will struggle to get far because their interview technique is appalling and they don’t know how to communicate with people.” “Presentation practice is definitely a bonus on our course.” 6.6 Professional institutions and further study Most of the students in Groups A and B from the core engineering courses were student members of their respective institutions and intended to work towards achieving their CEng. Group C who were studying Industrial Information Technology had very little interest in joining any professional institution. None of the students were very interested in further studying unless it was job specific. “I’d rather go and do a job, get to know what it’s all about and work up.” “I’m just sick of learning stuff and not really knowing why.” 7 LESSONS FOR LECTURERS The views expressed by the students in each group were very similar and the actions that they suggest making to improve their learning experiences are quite restrained and not beyond any member of academic staff. They want to be treated with respect and for lecturers to take the time to understand their needs and to make the courses relevant to them and their chosen careers. They want lecturers to fully prepare their lectures and arrive on time with clear overheads and handouts. They want lecturers to find out what they actually know before making assumptions about their level of knowledge, which could leave them completely at sea. They want lecturers to make eye contact with them and ensure that they can be heard in the lecture theatre. They want lecturers who are willing to spend some time with them when they have problems. They want the course content to be placed in an industrial context and they want lots of opportunities to place the theory into practice through tutorials and laboratories. In fact, what the students want is simply good practice and it is a sad commentary on engineering education that these are the things that these students apparently so rarely experienced. 8 REVIEW OF THE PROCESS All of the groups were enthusiastic about being asked for their opinions, although they were a little disappointed that they had not been asked in earlier years when they might have been able to influence their own courses. The focus groups ran very smoothly and were successful in meeting the objective of obtaining a snap shot of student opinion on their learning experiences. Group C, who did not have any advance warning of the session, were less expressive and required more prompting than the other groups. As this was the last of the three groups, the prompting may have influenced their responses as the author had her own expectations derived from the previous two groups which were very similar in their composition. Given the similarity in the findings found from the three groups, it is likely that they fairly represent student opinion in the engineering field. It would be interesting to contrast these opinions with group studying a degree programme where different teaching methods are common, such art or drama. 9 CONCLUSIONS Through the focus groups conducted, a group of engineering students have expressed their views on their learning experiences. It is apparent from their comments, that they have expectations for their learning that it is perfectly possible for higher education establishments to meet. Simply by employing good practice in their lectures, lecturers can improve the quality of the students’ learning experience. 10 1 2 3 REFERENCES “An Evaluation of the Computers in Teaching Initiative and Teaching and Learning Technology Support Network”, 1998, HEFCE Report 98/47 “Engineering Education Issues in the UK”, 2002, Davis, L E, Eley, R M and Lamb, F M, to be presented at the IEE Engineering Education Symposium “The Voice of the Customer”, 1993, Griffin, A and Hauser, J R, Marketing Science. Vol 12, No 1, pp1-27