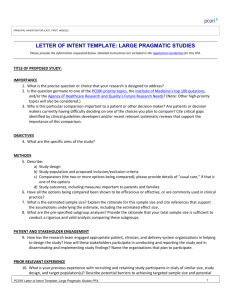

The PCORI Methodology Report

advertisement