Oncologist®

advertisement

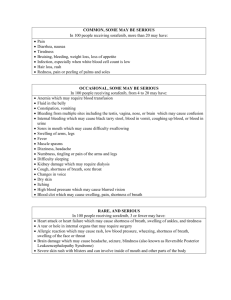

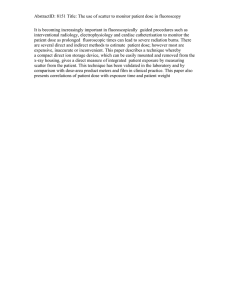

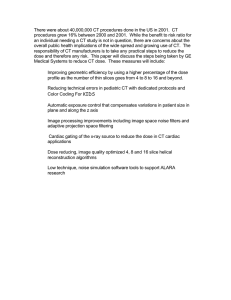

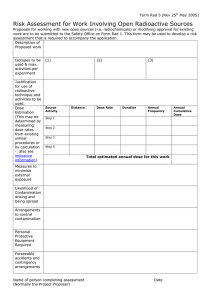

The Oncologist ® Symptom Management and Supportive Care ROGER ANDERSON,a AMINAH JATOI,b CAROLINE ROBERT,c LAURA S. WOOD,d KAREN N. KEATING,e MARIO E. LACOUTUREf a Penn State University College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA; bMayo Clinic Cancer Center, Rochester Minnesota, USA; cInstitut Gustav Roussy, Villejuif, France; dCleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland, Ohio, USA; eBayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, New Jersey, USA; f Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA Key Words. Hand–foot skin reaction • Acral erythema • Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia • Multikinase inhibitors Disclosures: Roger Anderson: Consultant/advisory role: Bayer Healthcare; Aminah Jatoi: None; Caroline Robert: Consultant/ advisory role: Pfizer-Bayer; Laura S. Wood: Honoraria: Bayer, Onyx, Pfizer, Wyeth; Karen N. Keating: Employment/leadership position: Bayer Healthcare; Mario E. Lacouture: Consultant/advisory role: Bayer, Onyx; Research funding/contracted research: Bayer, Onyx. The content of this article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is balanced, objective, and free from commercial bias. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by independent peer reviewers. ABSTRACT Background. The anticancer multikinase inhibitors (MKIs) are associated with cutaneous adverse events, including hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR), a condition affecting 20%– 40% of patients. Symptoms are usually mild, but can evolve into a painful condition that limits function and impacts quality of life (QoL), resulting in shortened cancer treatment duration or intensity. The goal of this study was to systematically review the literature on the prevention and palliation of MKI-associated HFSR, to identify areas for further clinical study, and to provide a foundation for evidence-based guidelines for HFSR management. Methods. Systematic searches of the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database, Cochrane Reviews, BIOSIS, CancerLit, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology website were conducted using search terms for cutaneous toxicities associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Articles were categorized (C) based on type of agent and cutaneous reaction as: C1 (MKI and HFSR); C2 (MKI and other cutaneous toxicity); C3 (other antineoplastic agents and HFSR); and C4, other. Results. Of the 2,069 abstracts screened, 350 (17%) met the criteria for C1–C4, with 56 (16%) coded as C1 with details of HFSR histology, pathogenesis, clinical outcome, QoL impact, and/or prevention and treatment approaches in MKI-treated patients. No randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) on prevention/palliation of HFSR were identified. Anecdotal evidence or expert opinion advocated protective measures, preventive and therapeutic skin care, systemic analgesics for pain, vitamin B6, and MKI dose modification. Conclusion. No articles containing evidence from RCTs on preventive/palliative approaches to MKI-asso- Correspondence: Roger Anderson, Ph.D., A210 Public Health Sciences, Penn State University College of Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA. Telephone: 717-531-2044; Fax: 717-531-4359; e-mail: randerso@hes.hmc.psu.edu Received November 1, 2008; accepted for publication February 2, 2009; first published online in The Oncologist Express on March 10, 2009. ©AlphaMed Press 1083-7159/2009/$30.00/0 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0237 The Oncologist 2009;14:291–302 www.TheOncologist.com Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Search for Evidence-Based Approaches for the Prevention and Palliation of Hand–Foot Skin Reaction (HFSR) Caused by the Multikinase Inhibitors (MKIs) 292 Treatment Strategies for Hand–Foot Skin Reaction vance development of evidence-based treatment guidelines. The Oncologist 2009;14:291–302 INTRODUCTION 17]. The primary objective of this literature review study was to determine the extent of evidence-based treatment for MKI-associated HFSR available in the peer-reviewed literature. A systematic and intensive review revealed that no evidence-based treatment algorithms exist for the effective prevention and treatment of cutaneous toxicities from MKIs [15]. Several experience-based practices are consistently seen and reported in the literature; these practices were presented in a recent publication summarizing the proceedings of an expert panel [5]. Chemotherapeutic agents such as capecitabine and doxorubicin have long been noted for their potential to cause skin toxicities that affect the hands and feet, varying in occurrence and severity by type of agent and dosing schedule [1–5]. Novel targeted therapies have recently demonstrated efficacy against several tumor types; however, use of several of the multikinase inhibitors (MKIs), such as sorafenib or sunitinib, has also led to the cutaneous toxicity known as hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) in 20%– 40% of treated patients [1, 2, 5]. The appearance of MKI-associated HFSR differs from the hand–foot skin toxicities (i.e., hand–foot syndrome [HFS]) seen with older chemotherapeutic agents [6, 7]. It usually presents as a mild-to-moderate cutaneous reaction [5, 8], is not age limited [3], and may evolve into a painful condition that limits daily functioning and affects quality of life (QoL) [1, 2, 4, 5]. The HFSR symptom burden experienced by the patient may eventually cause the oncologist to limit or reduce MKI treatment duration or intensity, or to end treatment. Signs and symptoms of HFSR may include pain, swelling, numbness, tingling, redness of the skin of the hands or feet, and flat blisters or hyperkeratotic lesions [9 –12]. As the hyperkeratotic areas thicken, scaly lesions resembling skin calluses surmount the erythematous patches. In high-grade, fully developed lesions, large tense blisters can develop [12]. The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE, v3.0) grading system for dermatologic toxicities [13], the most widely used method of grading for HFSR [3, 5], is shown in Table 1. The grading system used in the sorafenib U.S. prescribing information, which is more descriptive and specific to HFSR symptoms reported with sorafenib, also is shown [14]. Grade 1 HFSR is characterized by numbness, dysesthesia, paresthesia, tingling, painless swelling, and erythema or discomfort of the hands or feet that does not disrupt the patient’s normal activities. Characteristics of grade 2 HFSR include painful erythema and swelling of the hands or feet and/or discomfort affecting the patient’s normal activities. Grade 3 HFSR is characterized by moist desquamation, ulceration, blistering, or severe pain of the hands or feet, or severe discomfort that causes the patient to be unable to work or perform activities of daily living. Prompt identification and management of HFSR may be essential to facilitate the continuation of MKI therapy [15– METHODS Searches of the peer-reviewed literature were conducted via the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the BIOSIS and CancerLit databases listed in the archives through August 31, 2008. Literature search terms were broad based to capture skin toxicities associated with chemotherapy and were not specific to a certain agent or treatment approach. The searches used variations and synonyms of the key word “hand–foot syndrome” including hand–foot skin reaction, acral erythema, palmar– plantar erythrodysesthesia, acral erythema, acral erythrodysesthesia, Burgdorf reaction, and toxic erythema of the palms and soles, among other variations of the terms already stated. Medical subject heading (MeSH) searches were conducted using the terms skin disease, hand injuries– chemically induced, and erythema and were combined with MeSH terms, including antineoplastic agents and protein kinase inhibitors. The names of specific agents entered into the MeSH search included: sorafenib, sunitinib, gefitinib, erlotinib, temsirolimus, capecitabine, gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, tegafur, emitefur, vinorelbine, liposome-encapsulated or continuous-infusion doxorubicin, floxuridine, cytarabine, methotrexate, palifermin, docetaxel, cisplatin, clofarabine, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin, etoposide, fluorouracil, hydroxyurea, 6-mercaptopurine, paclitaxel, 6-thioguanine, and troxacitabine [18]. Additional searches focused on the toxicity of anticancer agents, patient management, and general cutaneous reactions to kinase inhibitors. When retrieval results exceeded 1,000 records, queries were limited to recent English-language clinical studies, meta-analyses, reviews, or practice guidelines. Additional articles that were similar or related to those already found were either brought to our Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 ciated HFSR have been published. Systematic study of optimal treatment strategies for HFSR is needed to ad- Anderson, Jatoi, Robert et al. 293 Table 1. Clinical features of HFSR and patient-reported symptoms [13, 14, 24] NCI-CTCAE v3.0 grading for Skin toxicity grade (sorafenib PI) Grade HFSR [13] [14] Minimal skin changes or dermatitis (e.g., erythema) without pain Numbness, dysesthesia, paresthesia, tingling, painless swelling, erythema or discomfort of the hands or feet that does not disrupt the patient’s normal ADLs Grade 2 Skin changes (e.g., peeling, blisters, bleeding, edema) or pain, not interfering with function Painful erythema and swelling of the hands or feet and/or discomfort affecting the patient’s ADLs Grade 3 Ulcerative dermatitis or skin changes with pain interfering with function Moist desquamation, ulceration, blistering, or severe pain of the hands or feet or severe discomfort that causes the patient to be unable to work or perform ADLs ● Numbness ● Unpleasant sensations when touching ordinary things ● A burning or prickly feeling ● Tingling ● Painless swelling ● Redness or discomfort of hands or feet ● None of these symptoms affect the patient’s ADLs One or more of the following: ● Painful redness ● Swelling ● Skin thickening of the hands or feet ● Symptoms create discomfort, but do not affect the patient’s ADLs One or more of the following: ● Scaling or shedding of the skin ● Open sores ● Blistering ● Skin thickening ● Severe pain of the hands or feet ● Severe discomfort that causes the patient to be unable to work or perform ADLs Abbreviations: ADL, activity of daily living; HFSR, hand–foot skin reaction; NCI-CTCAE, National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; PI, prescribing information. attention by expert panel members for further scrutiny or appeared in abstracts presented at recent American Society of Clinical Oncology congresses. Included for review in this study were all citations categorized (C) as C1 (pertaining to MKI-associated HFSR) and containing details on histology, pathogenesis, incidence, QoL, impact, treatment, or prevention. This literature was distinguished from related published material categorized as: C2 (citations that focused on MKI-associated skin reactions other than HFSR such as acneiform eruptions or skin rash histology, pathogenesis, incidence, treatment, or prevention); C3 (citations that focused on antineoplastic agents other than MKIs, such as capecitabine, doxorubicin, etc.); or C4 (citations that did not focus on clinical details of pathophysiology or treatment of HFSR/HFS but on other issues related to HFSR such as complications, study design issues, health care policy, or patient needs). Copies of articles were obtained and reviewed for all retained citations reporting clinical results of patient treatment approaches regardless of: (a) sample size or study design, (b) whether they were reviews of the www.TheOncologist.com scientific literature on HFSR treatment or outcomes, and (c) whether they were case studies. Excluded from further review were C1 articles that solely presented attitudes or opinions regarding HFSR without reference to any of the above inclusion criteria. Each citation was judged independently by two reviewers. Any discrepancies that arose regarding inclusion were resolved either by clarification followed by unanimous agreement or after review of the full article in question. Finally, we considered “evidence” as data or information that originated from objective tests of efficacy in clinical or case studies published in the scientific literature rather than from anecdotal observations. RESULTS In total, 2,069 abstracts were identified. All were screened for consistency with the search objectives. Abstracts covering the wrong condition or topics unrelated to antineoplastic therapy were eliminated. A total of 350 abstracts (16%) met the criteria for inclusion in C1–C4 (Fig. 1) and were stored in a reference database. Fifty-six (16%) were in- Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Grade 1 Symptoms [24] Treatment Strategies for Hand–Foot Skin Reaction 294 Database Literature Search NLM PubMed Database, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, BIOSIS and CancerLit Databases, ASCO Congress Abstracts Search terms: hand-foot skin reaction, hand-foot skin syndrome, etc., AND antineoplastic agents, protein kinase inhibitors, multikinase inhibitors, etc. 2,069 Citations 350a Citations MKI-Associated Skin Reactions Category 1 (C1) 56 Citations a Category 2 (C2) 12 Citations Cytotoxic ChemotherapyInduced Skin Reactions Category 3 (C3) 270 Citations Category 4 (C4) 19 Citations 7 articles contained content that required that they be placed into more than 1 category. Figure 1. Classification of retrieved articles. Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; MKI, multikinase inhibitor; NLM, National Library of Medicine. cluded in C1, and 270 (80%) were included in C3. None of the C1 or C3 articles on prevention/palliation approaches to HFSR were reports from randomized, controlled trials. Findings from the C1 articles follow. Prevention Approaches for MKI-Associated HFSR Evidence and reports on prevention and palliation of HFSR relevant to developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines are shown in Table 2. Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of MKI-associated HFSR in the examined literature were based on: practices implemented during clinical trials of MKI agents, postmarketing practices, approaches derived from personal clinical experiences of the authors, and strategies used for chemotherapy-induced HFS (non-MKI agents) but applied to HFSR resulting from MKI therapy. The range of treatment goals and prophylactic recommendations identified included: (a) controlling the presence of plantar hyperkeratosis, a putative risk factor for HFSR, by prophylactic removal of the hyperkeratotic areas followed by application of a moisturizing cream; (b) pedicures; and (c) the cushioning of callused areas by means of soft or padded shoes [19, 20]. Among other approaches were the prophylactic use of exfoliating products applied to the calluses [17] and administration of prophylactic pyridoxine (vitamin B6). The role of these recommendations in preventing chemotherapy-induced HFS remains under debate [21–23]. Recommendations on Patient Education Prior to Initiation of Drug Therapy Because most MKIs are self-administered oral medications, effective patient education about HFSR prior to commencement of therapy and guidance on skin care and protection is another strategy for prevention [4]. Oncology providers are encouraged to listen to patients’ concerns, offer options to enhance patient comfort, and identify treatment issues early [17]. No studies were found that tested the efficacy of patient education approaches for HFSR (e.g., printed material, video or photographic aides, or other media) [15, 24] on the likelihood of developing HFSR, or the severity of symptoms. Treatment/Palliation Approaches for Management of Symptoms of MKI-Associated HFSR Grade 1 Clinical goals for grade 1 HFSR (Table 3) as cited in the literature included instituting supportive measures, con- Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Independent Reviewer Screening Anderson, Jatoi, Robert et al. 295 Table 2. Recommendations for prophylactic management of hand-foot skin reaction Clinical goals/objectives Recommendations Source Screen for pre-existing plantar hyperkeratosis Prophylactic removal of the hyperkeratotic areas Prophylactic skin care Prophylactic systemic treatments Manicure or pedicure before and during treatment to remove hyperkeratosis ● Emollients ● Topical exfoliating products (salicylic acid and urea-based; e.g., Kerasal威; Alterna LLC, Whippany, NJ); ureacontaining prescription agents (e.g., Keralac威; Doak Dermatologics, Fairfield, NJ) to treat hyperkeratotic calluses ● Pedicure before treatment; manicure and pedicure before and during treatment with follow-up emollient; Keralac威 to treat hyperkeratotic calluses Wear well-fitting, soft shoes (e.g., sandals), foam-type absorbing soles, and shock absorbers to relieve painful pressure points Preventive administration of pyridoxine (doses of 50–150 mg/day) Glucocorticoidsa Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitorsb Personal experience or recommendation of the authors Personal experience or recommendation of the authors [8, 10, 11, 19] Personal experience or recommendation of the authors Personal experience or recommendation of the authors [7, 11, 15, 17, 20, 25, 38, 45] Personal experience or recommendation of the authors [2, 8, 17] Personal experience or recommendation of the authors [3, 10, 19, 20] Work of Vukelja et al. [46] in a patient with 5-FU–induced PPE; cited by others Opinion of the author Work of Lin et al. [47] with capecitabine and celecoxib; cited by others [3, 16, 46, 47] [7–11, 19] a Route of administration is not identified; no evidence of successful use. Effective as a systemic approach for prophylaxis of chemotherapy-associated hand–foot syndrome (5-FU, capecitabine, tegafur, emitefur, vinorelbine, doxorubicin, irinotecan, cytarabine, floxuridine), as well as sorafenib. Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; PPE, palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia. b tinuation of MKI treatment, control of hyperkeratotic areas, maintaining the moisture of the skin, and continuing patient education on skin care and protection. Specific approaches employed to achieve these goals included the use of keratolytics such as 40% urea and/or salicylic acid to aid in the natural exfoliation of the callused areas followed by cushioning of the affected regions with gel inserts or the use of soft shoes. Frequent application of emollients and creams may be important to maintain moisture of the skin and to prevent cracks or breaks in dermal integrity. A dermatologic referral of patients with unique skin presentations or those who fail to respond to HFSR treatment, combined with active collaboration www.TheOncologist.com among dermatologists, podiatrists, oncologists, and oncology nurses, was recommended. Unfortunately, none of the C1 publications covering recommendations for grade 1 MKI-associated HFSR presented scientifically collected evidence on the benefits of adherence to these general treatment strategies. All of the recommendations were based on the personal experience of the authors or case studies. Grade 2 No recommendations are cited in the literature for management approaches specific to grade 2 MKI-associated HFSR involving compounds or procedures for skin care or symp- Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Protection of pressuresensitive areas of the hands and feet Suitable podiatry care Reference(s) Treatment Strategies for Hand–Foot Skin Reaction 296 Table 3. Recommendations for management of grade 1 hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) Clinical goals/objectives Recommendations Source Dermatology referral and management Highly inflammatory lesions Cushioning the callused areas to relieve discomfort Local application of occlusive emollients to maintain moisture and treat dry skin Dose adjustment for grade 1 HFSR seen with sorafenib Footwear: gel inserts may provide some relief; loose-fitting shoes or slippers Analgesics: low- to moderate-dose analgesics; applying sunburn-relief spray to affected areas when needed Local/regional cooling, cold compresses: cold compresses/ice packs for pain relief; cooling battery or cooling hand and foot baths to relieve the symptoms Foot soaks: soaking feet in magnesium sulfate to soften calluses and reduce pain upon pressure Frequent application of highly occlusive emollients Emollient and urea-based creams may provide comfort and softening of the lesions Diligent application of creams and lotions especially to palms and soles Keep affected areas soft and pliable to prevent cracks or breaks in skin integrity Continue treatment with sorafenib and consider topical therapy for symptomatic relief tom control. Clinical goals for grade 2 HFSR included controlling hyperkeratosis, cushioning callused areas, moisturizing the skin, controlling symptoms, and relieving discomfort. The specific treatment approaches cited for grade 1 HFSR also applied to grade 2 HFSR (Table 4). The major approach used to control grade 2 HFSR is described in the reviewed literature as dose adjustment of MKIs. Recommendations for dosage or regimen adjustments for sorafenib were based on the proceedings from the expert panel [5] and were based on whether this was the first occurrence of grade 2 HFSR or a second, third, or fourth occurrence (Table 4). Personal experience of the authors [3, 36, 45] Personal experience of the author [4] Personal experience of the authors [4, 7, 8, 11, 14, 19, 37, 38, 48] Cited work of others [11] Personal experience of author Case study cited by the author [34, 36]; cited work of others [2,12] Personal experience of the author [15, 19] [3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 34, 36, 49, 50] Personal experience of the authors [11, 36] Expert panel [5] Grade 3 Clinical goals for grade 3 HFSR included symptom reduction and prevention of further progression [3, 25–27]. Specific supportive measures included topical therapies such as cortisone creams and topical antibiotics. Systemic strategies to reduce symptoms and prevent further progression included pyridoxine in doses of 50 –150 mg/day [3, 25–27]. The efficacy of corticosteroids has not been established. The cornerstone of the treatment recommendations is interruption of MKI treatment for a minimum of 7 days until toxicity has resolved to grade 0 or 1 (Table 5) and a decrease by one dose level (sorafenib, 400 mg daily or 400 mg every Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Local control of symptoms at first signs of paresthesias Control hyperkeratosis through products that aid in natural exfoliation Early and appropriate dermatologic management Active collaboration between dermatologists and medical oncologists or urologists Over-the-counter products help patients maintain a sense of control over their treatment plan Decrease thickness of hyperkeratotic areas with keratolytics, such as 40% urea and/or salicylic acid Nonprescription emollient Twice-daily application of the products appears adequate Dermocorticoids are unproven Reference(s) Anderson, Jatoi, Robert et al. 297 Table 4. Recommendations for management of grade 2 hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) Clinical goals/objectives Recommendations Reference(s) Expert panel [5] See recommendations for grade 1 HFSR (Table 3) On the first occurrence of grade 2 HFSR, promptly institute supportive measures such as topical therapy for symptomatic relief and consider a dose decrease of sorafenib to 400 mg daily for a minimum of 7 days and up to 28 days If toxicity resolves to grade 0 or 1 after dose reduction, increase to registration dose: sorafenib, 400 mg twice daily If toxicity does not resolve to grade 0 or 1 despite dose reduction, interrupt MKI treatment for a minimum of 7 days and until toxicity has resolved to grade 0 or 1 When resuming treatment after dose interruption, begin at reduced dose: sorafenib, 400 mg daily If toxicity is maintained at grade 0 or 1 at reduced dose for a minimum of 7 days, increase to registration dose On the second or third occurrence of grade 2 HFSR, follow steps for first occurrence; upon resuming MKI treatment, decrease dose by one dose level (sorafenib, 400 mg daily or 400 mg every other day); decision whether to re-escalate dose should be based on clinical judgment and patient preference On the fourth occurrence of grade 2 HFSR, the decision whether to discontinue MKI treatment should be based on clinical judgment and patient preference Abbreviation: MKI, multikinase inhibitor. other day) when resuming treatment. Specific recommendations for resumption of treatment and for a second or third occurrence of grade 3 HFSR can be found in Table 5 [5]. Overall, there are limited evidence-based data to guide selection of the most effective and specific measures on the management of MKI-associated grade 3 HFSR. The literature search identified a single uncontrolled HFSR treatment study of 12 patients predominantly with grade 3 toxicity [26], and reported improvement in skin toxicity with treatments including single-agent 40% urea cream, 0.1% tazarotene cream, and 5% fluorouracil cream. The recommendations and treatment approaches listed in Table 5 are based solely on clinical experience, case studies, or uncontrolled trial designs. In a case study of three patients on a sunitinib treatment regimen, the occurrence of adverse effects diminished during the rest period within the treatment cycle [28] and/or upon dose reduction of sunitinib [29]. Clinical reports of grade 3 HFSR treatment [4, 19] have www.TheOncologist.com observed that toxicity may resolve within a few days by employing approaches such as dose interruption/reduction and systemic or local supportive measures, after which treatment with MKIs can be resumed. In a dermatologic subanalysis of the Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial [30], grade 3 HFSR resulted in 50% dose reductions in two of the 43 renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients receiving sorafenib, and toxicity resolved in 3– 4 weeks without long-term sequelae [31]. Upon restoration of full-dose sorafenib, HFSR recurred in only one of those patients. No sorafenib-induced nevi modifications were observed; however, since this study, several nevi eruptions have occurred in patients treated with sorafenib [32, 33]. In a single case study of a patient with RCC who presented with HFSR after treatment with sorafenib, discontinuation of treatment for 14 days combined with topical treatment and mild analgesics for pain led to resolution of the HFSR [34]. After the HFSR had resolved, sorafenib was Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 General goals for controlling hyperkeratosis, cushioning callused areas, moisturizing the skin, controlling the symptoms, relieving discomfort Dose adjustment for grade 2 HFSR seen with sorafenib Source Treatment Strategies for Hand–Foot Skin Reaction 298 Table 5. Recommendations for management of grade 3 hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) Clinical goals/objectives Recommendations Source Local topical strategies to reduce symptoms and prevent further progression Dose adjustment recommendations for grade 3 HFSR seen with sorafenib Personal experience or recommendation [3, 7, 20, 51] of the authors Uncontrolled observational study [26] Work of Vukelja et al. [46] in a patient with 5-FU–induced PPE; cited by others [3, 15, 20, 46] Mechanism of action is still Personal experience or recommendation unknown of the authors Only in a few exceptional cases is systemic administration of corticosteroids or antihistamines indicated to complement therapy Efficacy of corticosteroids has not been established On the first occurrence of grade 3 Expert panel [5] HFSR, institute supportive measures such as topical therapy for symptomatic relief and interrupt MKI treatment for a minimum of 7 days and until toxicity has resolved to grade 0 or 1 When resuming treatment after dose interruption, decrease by one dose level (sorafenib, 400 mg daily or 400 mg every other day) If toxicity is maintained at grade 0 or 1 at reduced dose for a minimum of 7 days, increase by one dose level (sorafenib, 400 mg twice daily or 400 mg daily) On the second occurrence of grade 3 HFSR, follow steps for first occurrence; upon resuming MKI treatment, decrease dose by one dose level (sorafenib, 400 mg daily or 400 mg every other day); decision whether to re-escalate dose should be based on clinical judgment and patient preference On the third occurrence of grade 3 HFSR, the decision whether to discontinue MKI therapy should be based on clinical judgment and patient preference Abbreviation: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; MKI, multikinase inhibitor; PPE, palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia. Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Systemic strategies to reduce symptoms and prevent further progression Treatment of blisters and erosions with a wet disinfectant Emollient and urea-based creams may provide comfort and softening of the lesions Diligent application of creams and lotions especially to palms and soles For severe forms of HFSR, the combination of a cortisone cream and topical antibiotic such as fluconazole or gentamicin is recommended Efficacy of dimethylsulfoxide has not been substantiated Pyridoxine may be beneficial (doses of 50–150 mg/day) Reference(s) Anderson, Jatoi, Robert et al. 299 Table 6. Skin care products for use in hand–foot skin reactions (HFSR) (adapted from [17, 36]) Skin care products for acral erythema/xerosis Product information Cetaphil威 (Galderma Laboratories, Ft. Worth, TX) skin cleaners, Aveeno威 (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) shower gel Udderly Smooth威 (Redex Industries, Salem, OH), Gold Bond威 (Chattem, Chattanooga, TN), Aveeno威 Bag Balm威 (Dairy Association Co., Lyndonville, VT) Eucerin威 (Beiersdorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) Cream Eucerin威 Dry Skin Therapy Aquaphor威 (Beiersdorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) Healing Ointment Kerasal威 (Alterna LLC, Whippany, NJ) Blue Lizard威 (Crown Laboratories, Johnson City, TN) resumed at a 50% dose reduction without any further incidence of toxicity. The range and variety of skin care products that have been cited in the literature as having treatment potential for the management of HFSR are listed in Table 6. DISCUSSION No evidence-based treatment algorithms exist for cutaneous toxicities of the MKIs in the dermatologic or oncologic literature [17, 35]. Our systematic review of the published literature through August 31, 2008, revealed that current recommendations on the clinical approaches to HFSR prevention and treatment are largely anecdotal, derived from case reports, based on practices implemented during clinical trials to optimize MKI treatment duration, culled from postmarketing practices, or extrapolated from approaches used for chemotherapy-induced HFS (e.g., capecitabine, 5-fluorouracil [5-FU], doxorubicin) rather than specifically from MKIs. The literature on treatment of HFS stemming from the use of chemotherapeutic agents and the current recommendations may or may not be appropriate in treating the side effects of newer agents [36]. Although HFSR in patients treated with MKIs may resemble the more commonly known presentation seen in patients receiving capecitabine, fluorouracil, or doxorubicin [4], when the condition is associated with MKI treatment it is thought to be a distinct entity [1, 5]. Time to onset of MKI-associated HFSR is noted to be much shorter (14 –28 days) [11, 37, 38] than for chemotherapy-induced HFS; MKI-associated HFSR is typically more localized than HFS from other antineoplastic www.TheOncologist.com Thicker products with more intense moisturizing properties than basic lotions; anti-itch formulations are available Contains dimethicone 1%, camphor 0.1%, and lidocaine Contains cetearyl alcohol, dimethicone, menthol, and urea May provide “cooling” effect from eucalyptus Best used at night due to greasy formulation Contains urea and alpha hydroxy acid Petrolatum 41% Salicylic acid 5% exfoliates and softens skin; urea 10% moisturizes skin UV A and B sunblock, water resistant agents and most often affects the pressure zones of the feet (e.g., the skin facing the heels, heads of the metatarsals, areas of friction with shoes) in a symmetrical pattern [1, 4]. Thus far, there is no evidence-based rationale to advocate for any of the preventive measures for chemotherapyinduced HFS for prophylaxis of MKI-associated HFSR [25, 36]. Therefore, it will be important to understand the similarities and differences between the pathogenesis, histology, clinical course, and complications of dermatologic reactions (HFS) induced by traditional agents, such as capecitabine and 5-FU, and those induced by MKIs (HFSR) to develop appropriate, rationally developed interventions [36]. Among the C1 articles reviewed, none were randomized, controlled trials designed to test HFSR management approaches. In addition, none of the ancillary, prospective, observational, or case– control studies described in the literature had been designed to test the efficacy of distinct treatment approaches in the management of HFSR on either clinical or patient-reported outcomes. The phase I–III studies that have thus far established MKIs, such as sorafenib, as effective therapeutic agents for metastatic cancers have not included the systematic study of HFSR management approaches [30, 39, 40]. Thus, a major conclusion from our study points to the need for additional research to test and compare the various recommendations for prevention and treatment of HFSR and to further elucidate the most efficacious methods for treating the side effects observed with newer targeted therapies [36]. Specifically, research is needed on: (a) appropriate patient education on prophylaxis for HFSR and its effects on patient outcomes; (b) how often Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 Norwegian Formula: Smoothing Relief Anti-Itch Moisturizer by Neutrogena威 (Neutrogena, Los Angeles, CA) Norwegian Formula: Foot Cream by Neutrogena威 Nondeodorant, fragrance-free products 300 conjunction with accepted criteria, such as the NCICTCAE v3.0 [13, 41]. In order to apply a systematic approach to future research and development of evidence-based solutions for HFSR, it is essential to develop an evidence base for HFSR prevention and management goals and endpoints from rigorous study designs comparing clinical treatment alternatives or patient management strategies recommended in the scientific literature [44]. With regard to treatment goals, it was noted in our review that there is general consensus that hyperkeratosis is a risk factor for MKI-associated HFSR, and that these areas should be removed prophylactically before and during treatment, cushioned for orthopedic redistribution, and covered with emollient and/or keratolytic creams to moisturize and aid in natural exfoliation, respectively. However, the literature does not contain details on how to remove the hyperkeratosis or how to cushion these areas. Nor is there consensus on which specific agents to use, strength of the agent, dosage, duration or frequency, and supportive care practices. Thus, prospective studies, preferably randomized, double-blind, controlled designs of adequate size to detect meaningful effects, are needed to identify optimal treatment approaches developed though clinical experience to control the risk for HFSR, and to benefit patients. In addition to guideline evidence on effective treatments, prospective studies with health services research designs will be informative to identify optimal initiation of treatment: prophylaxis versus reactive treatment (waiting until symptoms arise and treating them reactively) as well as other elements of clinical practice that support clinical management of HFSR. Some of these considerations include identifying effective care processes such as the scheduling of visits with an oncologist for HFSR screening and monitoring, how to best deliver effective patient education, and the value of referrals for specialist care. For patients with extensive hyperkeratosis prior to initiating MKI treatment, comparisons of “standard” optimal care by an oncology team versus an approach supplemented by specialist care from dermatologic or podiatric consults (e.g., to remove hyperkeratosis and advise on cushioning of pressure areas and proper footwear) merit study for effects on the development or progression of HFSR. For patients with mild disability related to skin toxicity, studies are needed to weigh the benefit of traditional therapeutic approaches such as referrals to allied health for evaluation for adaptive equipment and assistance with independent living in prolonging treatment and reducing disability. Finally, HFSR outcomes should not only include consensus ratings on grade or severity, but also ratings from the patient’s perspective on tolerability and health-related QoL. With the advancements noted above, clinicians will have a scientific Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 the patient should be seen by an oncologist or dermatologist after beginning treatment with MKIs; (c) how to accurately diagnose HFSR in its mild forms and recognize subsequent dermatologic complications; (d) how to effectively treat and remove the calluses on hands and feet without leading to increased HFSR damage and symptom burden; (e) providing guidance to both patients and providers on the best types of gel inserts, cushions, and soft footwear; (f) identifying the treatment strategies that are most effective at each grade of toxicity or severity; and (g) testing the effectiveness of specific emollients and keratolytic creams for preemptive or reactive treatment of MKI-associated HFSR. Efficacy studies on novel mechanism-based prophylactic or palliative therapy are needed to provide the data that may ultimately lead to the development of better tolerance of novel antineoplastic or targeted therapies with reduced dermatologic side effects [41]. A major pitfall of conducting such trials is the risk of ascribing an improvement to the palliative agent, when that improvement may represent the natural history of the dermatologic reaction or poor compliance with the inciting agent (MKI) [41]. Because dose reductions can postpone or undermine optimal anticancer treatment efficacy, the prevention and minimization of dermatologic adverse events through prompt recognition and management is an important goal. Treatment options will need to be adapted according to the availability of agents, reimbursement patterns, and national and international treatment guidelines [15]. Another important need is a better understanding of the psychological and social implications that dermatologic reactions have on patients receiving cancer treatment. Brief toxicity screens serve as poor substitutes for the measurement of patient well-being. None of the studies or reports in the reviewed literature included a detailed assessment of QoL and patient symptom burden. Tools for the assessment of patient response to preventive and palliative measures, whether newly developed or adapted, are required to advance research on HFSR outcomes; such tools are essential for clinicians to gain an understanding of the full burden that HFSR imposes on daily life and whether the condition is moderated by patient characteristics, location of HFSR, and other comorbidities. In this regard, the dermatology literature shows that several questionnaires are available for patients to complete on a regular basis and thus provide information about their condition to aid investigators in understanding whether the dermatologic symptoms are worsening or improving and their impact on the patient’s QoL [42, 43]; however, none of the available measurement tools were developed to specifically assess HFSR. Detailed questionnaires for patient completion should be used in Treatment Strategies for Hand–Foot Skin Reaction Anderson, Jatoi, Robert et al. basis for selecting and delivering the most effective therapy to prevent and manage HFSR. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES 1 2 Cancer.net. Skin Reactions to Targeted Therapies. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2007. Available at http://www.cancer. net/patient/Diagnosis⫹and⫹Treatment/Treating⫹Cancer/Managing⫹ Side⫹Effects/Skin⫹Reactions⫹to⫹Targeted⫹Therapies, accessed August 31, 2008. Chu D, Lacouture ME, Fillos T et al. Risk of hand-foot skin reaction with sorafenib: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol 2008;47: 176 –186. lished literature on HFSR associated with MKIs, although a number of treatments have been applied to prevent and treat HFSR, evidence establishing their efficacy using scientifically and clinically sound methods is missing. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study has been supported by an educational grant from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Conception/design: Roger Anderson, Karen N. Keating, Mario E. Lacouture Collection/assembly of data: Roger Anderson, Karen N. Keating Data analysis: Roger Anderson, Karen N. Keating Manuscript writing: Roger Anderson, Aminah Jatoi, Caroline Robert, Laura S. Wood, Karen N. Keating, Mario E. Lacouture Final approval of manuscript: Roger Anderson, Aminah Jatoi, Caroline Robert, Laura S. Wood, Karen N. Keating, Mario E. Lacouture The authors take full responsibility for the content of the paper (organizing the published literature/preparing the initial and all subsequent drafts of the manuscript/collating the comments of authors), but thank Aurora O’Brate, Ph.D., from Ogilvy Healthworld, supported by Bayer Healthcare, for her assistance in copyediting the manuscript (ensuring correct grammar, spelling, and readability), in preparing the manuscript for submission to The Oncologist (ensuring correct format of references, style), and in collecting all forms required for submission to The Oncologist (disclosures). treated with sorafenib: A clinicopathological study of cutaneous manifestations due to multitargeted kinase inhibitor therapy. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158:592–596. 13 National Cancer Institute. CTC v2.0 and Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2006. Available at http://ctep.info.nih.gov/reporting/ctc.html, accessed August 31, 2008. 14 Nexavar [package insert]. West Haven, CT: Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, 2007. 3 Janusch M, Fischer M, Marsch WC et al. The hand-foot syndrome—a frequent secondary manifestation in antineoplastic chemotherapy. Eur J Dermatol 2006;16:494 – 499. 15 Bhojani N, Jeldres C, Patard JJ et al. Toxicities associated with the administration of sorafenib, sunitinib, and temsirolimus and their management in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2008;53:917–930. 4 Wood LS, Manchen B. Sorafenib: A promising new targeted therapy for renal cell carcinoma. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2007;11:649 – 656. 5 Lacouture ME, Wu S, Robert C et al. Evolving strategies for the management of hand-foot skin reaction associated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. The Oncologist 2008;13:1001–1011. 16 Lacouture ME, Basti S, Patel J et al. The SERIES clinic: An interdisciplinary approach to the management of toxicities of EGFR inhibitors. J Support Oncol 2006;4:236 –238. 6 Autier J, Mateus C, Wechsler J et al. [Cutaneous side effects of sorafenib and sunitinib.] Ann Dermatol Venereol 2008;135:148 –153. In French. 7 Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: An update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:545–570. 8 Porta C, Paglino C, Imarisio I et al. Uncovering Pandora’s vase: The growing problem of new toxicities from novel anticancer agents. The case of sorafenib and sunitinib. Clin Exp Med 2007;7:127–134. 9 Deslandres M, Sibaud V, Chevreau C et al. [Cutaneous side effects associated with epidermal growth factor receptor and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.] Ann Dermatol Venereol 2008;Spec No 1:16 –24. In French. 10 Pföhler C, Ugurel S. [Cutaneous reactions to molecular targeted therapies.] Hautarzt 2008;59:814 – 820. In German. 17 Wood L. Managing the side effects of sorafenib and sunitinib. Community Oncol 2006;3:558 –562. 18 Webster-Gandy JD, How C, Harrold K. Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE): A literature review with commentary on experience in a cancer centre. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2007;11:238 –246. 19 Robert C. [Cutaneous side effects of antiangiogenic agents.] Bull Cancer 2007;94 Spec No:S260 –S264. In French. 20 Staehler M, Haseke N, Schöppler G et al. [Managing the side effects of angiogenetic inhibitors in metastatic renal cell carcinoma.] Urologe A 2006; 45:1333–1342. In German. 21 Gressett SM, Stanford BL, Hardwicke F. Management of hand-food syndrome induced by capecitabine. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2006;12:131–141. 11 Robert C, Soria JC, Spatz A et al. Cutaneous side-effects of kinase inhibitors and blocking antibodies. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:491–500. 22 Lee S, Lee S, Chun Y et al. Pyridoxine is not effective for the prevention of hand foot syndrome (HFS) associated with capecitabine therapy: Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:9007. 12 Yang CH, Lin WC, Chuang CK et al. Hand-foot skin reaction in patients 23 Mortimer JE, Lauman M, Tan B et al. Pyridoxine treatment and prevention www.TheOncologist.com Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 It is important to identify effective, safe, and tolerable treatment options for prevention and palliation of cutaneous reactions to chemotherapy agents. Common themes for prophylaxis and grade 1 HFSR were consistently repeated throughout the peer-reviewed literature, focusing on the importance of controlling the hyperkeratosis and removing the calluses, cushioning of the hands and feet, and the use of creams to aid in the natural exfoliation and moisturization of the skin. Management of more severe cases of HFSR was discussed with a focus on dose modification and drug rechallenge, optimizing drug delivery. These observations are consistent with the best practice recommendations from the recently published expert panel [5]. Good clinical practice, as currently implemented, would involve following the recommendations of the expert panel. In regard to the pub- 301 302 Treatment Strategies for Hand–Foot Skin Reaction of hand-and-foot syndrome in patients receiving capecitabine. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2003;9:161–166. 37 Ahmad T, Eisen T. Kinase inhibition with BAY 43–9006 in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10 (suppl):6388S– 6392S. 24 Skin reactions and cancer therapy—Guidelines for identifying and managing skin-related side effects during your therapy. West Haven, CT; Emeryville, CA: Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, 2008:1–13. 38 Lacouture ME, Boerner SA, Lorusso PM. Non-rash skin toxicities associated with novel targeted therapies. Clin Lung Cancer 2006;8(suppl 1):S36 – S42. 25 Eskens FA, Verweij J. The clinical toxicity profile of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) targeting angiogenesis inhibitors: A review. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42:3127–3139. 27 Scheithauer W, Blum J. Coming to grips with hand-foot syndrome. Insights from clinical trials evaluating capecitabine. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:1161–1168, 1173; discussion 1173–1176, 1181–1184. 28 Sutent [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs, 2007. 29 van der Veldt AA, van den Eertwegh AJ, Boven E. [Adverse effects of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor sunitinib, a new drug for the treatment of advanced renal-cell cancer.] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2007;151:1142–1147. In Dutch. 30 Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:125–134. 31 Autier J, Escudier B, Wechsler J et al. Prospective study of the cutaneous adverse effects of sorafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:886 – 892. 32 Bennani-Lahlou M, Mateus C, Escudier B et al. [Eruptive nevi associated with sorafenib treatment.] Ann Dermatol Venereol 2008;135:672– 674. In French. 33. Kong HH, Sibaud V, Chanco Turner ML et al. Sorafenib-induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:820 – 822. 40 Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378 –390. 41 Patiyil S, Chan SN, Jatoi A. New agents, new rashes: An update on skin complications from cancer chemotherapy. Curr Oncol Rep 2006;8:269 – 274. 42 Anderson R, Rajagopalan R. Responsiveness of the Dermatology-specific Quality of Life (DSQL) instrument to treatment for acne vulgaris in a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Qual Life Res 1998;7:723–734. 43 Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP et al. Measurement properties of Skindex16: A brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg 2001;5:105–110. 44 Pérez-Soler R, Delord JP, Halpern A et al. HER1/EGFR inhibitor-associated rash: Future directions for management and investigation outcomes from the HER1/EGFR inhibitor rash management forum. The Oncologist 2005;10:345–356. 45 Robert C, Escudier B. Cutaneous side effects of multikinase inhibitors used in renal cell cancer. Oncology News International 2007;May:1–20. 46 Vukelja SJ, Lombardo FA, James WD et al. Pyridoxine for the palmarplantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1989;111:688 – 689. 47 Lin E, Morris JS, Ayers GD. Effect of celecoxib on capecitabine-induced hand-foot syndrome and antitumor activity. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002;16(suppl 14):31–37. 48 Rudy SJ, Parham-Vetter PC. Percutaneous absorption of topically applied medication. Dermatol Nurs 2003;15:145–146, 150 –152. 34 Bajetta E, Procopio G, Verzoni E et al. Renal cell cancer and sorafenib: Skin toxicity and treatment outcome. Tumori 2007;93:201–203. 49 Kara IO, Sahin B, Erkisi M. Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia due to docetaxel-capecitabine therapy is treated with vitamin E without dose reduction. Breast 2006;15:414 – 424. 35 Grünwald V, Heinzer H, Fiedler W. Managing side effects of angiogenesis inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Onkologie 2007;30:519 –524. 50 Wilkes GM, Doyle D. Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2005;9:103–106. 36 Esper P, Gale D, Muehlbauer P. What kind of rash is it? Deciphering the dermatologic toxicities of biologic and targeted therapies. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2007;11:659 – 666. 51 Lopez AM, Wallace L, Dorr RT et al. Topical DMSO treatment for pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-induced palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1999;44:303–306. Downloaded from www.TheOncologist.com at EBSCO PUBLISHING DATA DELIVERY on April 7, 2009 26 Lacouture ME, Reilly LM, Gerami P et al. Hand foot skin reaction in cancer patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1955–1961. 39 Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24: 4293– 4300.