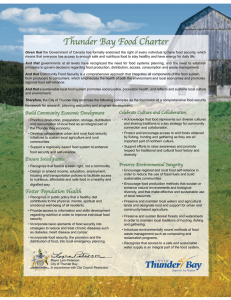

Poised for Development, Ready for Growth

advertisement