Voting Integrity - Columbia Law School

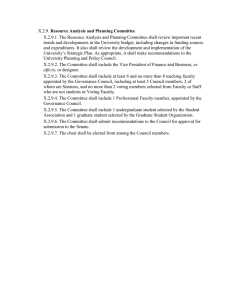

advertisement