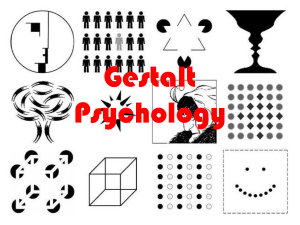

Gestalt Therapy an Introduction

advertisement