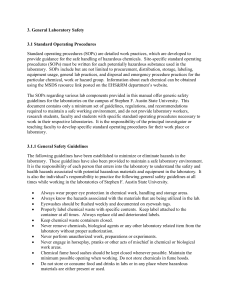

RR919 - Human factors that lead to non-compliance with

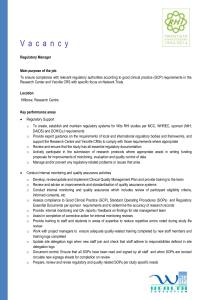

advertisement