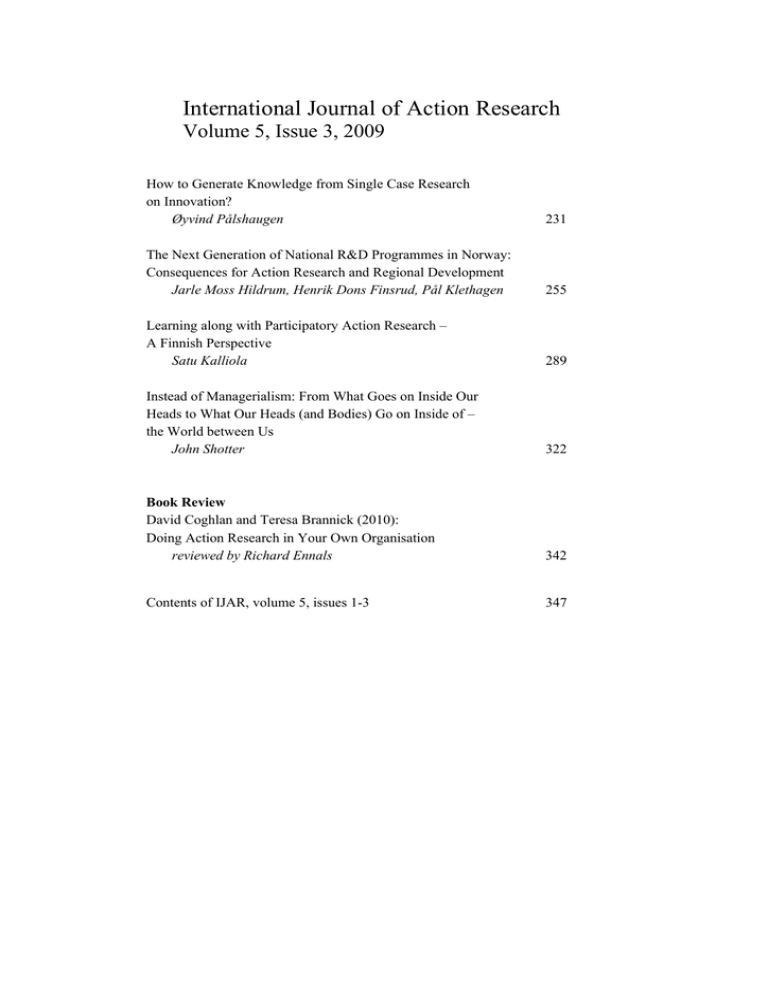

International Journal of Action Research

advertisement