climbing the technical ladder - The Clayman Institute for Gender

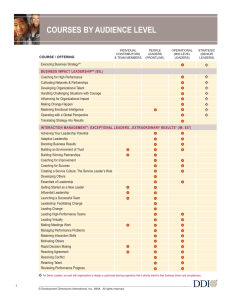

advertisement