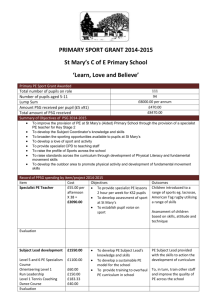

DfE external template

advertisement