Building the Creative Economy in Nova Scotia

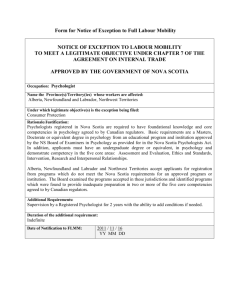

advertisement