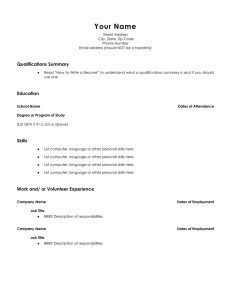

Structures and functions of Competency-based Education and

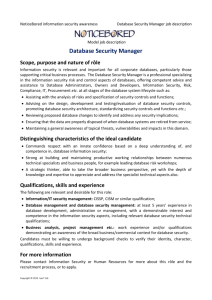

advertisement