Skills assessment in India

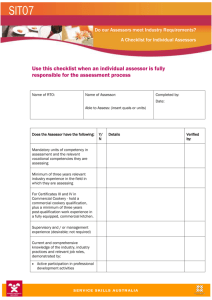

advertisement