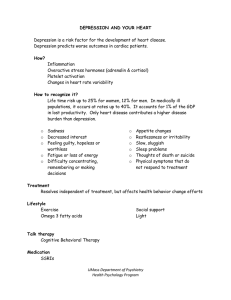

Chapter 2 Depression among Older Persons

advertisement