Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles

advertisement

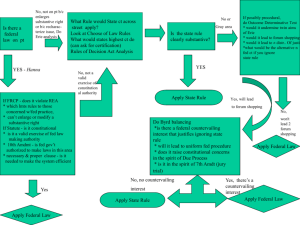

Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. Exxeed Econometrics 25 Rollins Place Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 858-531-5815 760-852-4367 1988, Revised 2010 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 2 The saying “The more things change the more they remain the same” may be true in economics as well as other fields of endeavor. This paper purports that this truism is relevant and will examine its consequences. Questions posed may be: To what extent is the present economic condition unique and to what extent is it experiencing past patterns and conditions; and how consistent are these patterns? By examining past business cycles, insight into these questions may be found. This paper will examine some of the aspects of business cycles, incorporate the concept of countervailing factors into the cycle model and correlate data with the hypothesized model: GNP= Yt ± ∆Yt peak (trough) cos (π/2 l X-Y l) + e where: Yt-trend line GNP - ∆Yt trough for 1≤Y≤0, 0≤X≤1 +∆Yt peak for 0≤Y≤1, 1≤X≤0 Figure 1 Business Cycle as represented by model The purpose, therefore, will be to determine the validity of such a model, its forecasting ability, that is whether turning points can be estimated, and inadvertently, discover the dynamics of inverse relationships upon which the model is based. Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 3 In determining the mechanics of business cycles, countervailing factors have largely been ignored. Although historically, increasing and decreasing variable changes can readily be seen in such relationships as money supply and interest rates, or inflation and unemployment; their incorporation into a complete business cycle has not been undertaken. As in the case in physical cycles, elements of the cycle have to exhibit changing antagonistic and synergistic relationships during the upward and downward swing in order for movement to posses momentum and be self-perpetuating. The approach in this study is relatively simple: incorporate key increasing and decreasing variables into the countervailing elements of the cycle, interchange these variables appropriately into countervailing elements and construct a model that should be self-sustaining. The degree to which economic and social phenomenon follow physical phenomenon may be limiting. Analogies are bound to be imprecise. Unlike mechanical systems, behavior is far from predictable. Economic activity may differ from cycle to cycle because of changes in structure, government policy, income distribution and so on. Variables that are predominate in one cycle may be insignificant in another. The concept of countervailing elements is based on inverse relationships in the cycle. For the sake of simplicity and mathematical conformity, these relationships are assumed linear. Originally the idea of the model was to average out the various inverse relationships (variables) into X and Y, creating two averaged opposite variables in which the maximum point in one would correspond to the minimum in the other. In order for maximum and minimum to fit the model equation, 0 represents minimum and 1 represents maximum while fractions represent proportions in-between. (Figure 1) However, as the study progressed it became evident that such a concise incorporation of the various elements would not be possible. What did become apparent is that money supply coincides with the model equation for the most part consistently while its counterpart, interest rates (inflation) was skewed. The pattern difference is illustrated in figure 2, 3, and 4. Other variable relationships and patterns in the cycle will be presented and interpreted, but for the most part this paper will deal with money supply, money demand, interest rates and inflation in conjunction with the postulated countervailing model. The idea of countervailing elements rather than independent and dependent variable relationships simply introduces the interdirectionality of the relationship and does not preconceive or preclude cause and effect. Money supply increases may cause interest rates to decrease but at the same token increases in interest rates (in an inflationary phase) may cause money supply to decrease through government policy to stem inflation. Or increases in interest rates (in an Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 4 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. expansionary period) may cause money supply to increase through private investment. pg. 5 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 6 Confusion as to cause and effect, and independence of variables is minimized by viewing these inverse relationships as independent countervailing elements in the overall cycle subject to the usual independent-dependent relationship of various degrees at different points or instances in the cycle. Moreover, the inverse countervailing element will be part of several independent variables determining the dependent countervailing element (factor), (ex. Y=f(X,z,h…). Because the value of the data is increasing in some instances (GNP, money supply…) maximum and minimum points were determined by calculating a trend line ( a regression line was determined by computer; midpoints, maximum, minimum were assigned from the observed cycle) through the variable’s data (Figure 1). Methodology Computer regression analysis was used to establish a trend line and measure points along the cycle. Time was the independent variable and data as supplied by Citidat computer records was the dependent variable. Both quarterly and monthly data was used. Peak, trough and midpoints of GNP were marked out on the regressed results. Patterns were established corresponding to GNP’s peak, trough, and midpoints. Conversely, from the variable-GNP pattern cycle, patterns were established for the relationships: Inflation-GNP Interest Rates-Money Supply Interest Rates-Debt Debt-GNP Savings-Debt (Interest Rates, Inflation) Savings-GNP Savings-Investment Investment-GNP Investment-Interest Rates (Inflation) Investment-Debt Net Exports-GNP Measurement for consistency (inconsistency) was determined by counting the number of quarters the cycle was off the pattern mark at midpoint, trough or peak. In this way, the error was analyzed by using the regression equation (y=a + bx +e) (Figure 4-a). The independent variable, x, becomes the cycle number and y, errornumber of quarters the cycle was off the pattern mark either at midpoint, trough or peak becomes the dependent variable. A zero error indicates perfect consistency while deviation from zero shows the extent of inconsistency. Soritec computer program was used for the computer regression analysis. The results gave: R2 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 7 (coefficient of determination), u (mean of dependent variable), Durbin Watson, coefficients a, b, t ratio, and standard deviation. A 95% confidence interval was, also, determined. Since industrial capacity closely coincided with GNP on a quarterly basis also since it is a percentage statistic more amenable to regression analysis and fits the model’s minimum and maximum requirements it was used as a proxy for GNP. As long as the mean (error) is within the standard deviation interval and close to y=o (zero error) of the proposed model there is a high probability of consistency and the model’s validity. Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 8 The interpretation of the 95% confidence level and the standard deviation is a bit tricky. Since these parameters are reflective of the normal bell shaped curve, the correlation-hypothesized model is dependent on the rejection of the alternative hypothesis, that is, the invalidity of the model’s correlation of the inflection point (midpoint, trough or peak) GNP and the inflection point of the proposed parameter such as money supply (Figures 17 & 18).Because computer regression analysis would only compute mean(z=0), standard deviation (z=1) of the data, and so on, the position of perfect zero is critical in determining consistency(Figure 4b). For instance, if the zero is outside the 95% confidence interval then we reject the correlation -hypothesized model (null hypothesis) and conclude that there is a 95% probabili ty that the hypothesis is invalid. If the zero is within the 95% confidence interval then a 95% probability of rejection can not be made. Similarly, the standard deviation (z score=1) of a normal bell shaped curve has a confidence level of 68%, an d the placement of y=zero at or just outside of the standard deviation has a 68% confidence of rejecting the correlation-hypothesized model (null hypothesis) if it is used as a rejection criterion. Conversely, there is a 32% confidence of accepting the null hypothesis if it is not used as the rejection point . In essence, as the difference between y=0 and the mean, u diminishes, this lowers the chance of rejecting the null hypothesis and heightens the probability of validating the model and its conclusions. Data and Statistical Results After examining data from 1945 to 1986 a pattern between GNP (capacity) and the various variables can be established. Figure 5 illustrates the direct and inverse changes in the relationship between money supply and inflation rate as the cycle changes. Figure 6 depicts a similar relationship between net export and exchange rate. In figure 7 thru 14, the relationship between phase changes for the various relationships is analyzed. The phase changes of the cycles are numbered 1,2,3,4. Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 9 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 10 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 11 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 12 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 13 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 14 From the computer data, the patter ns repeat themselves consistently. Statistically, change in inflection point consistency was measured for money supply and GNP (capacity); and net export and GNP (capacity). For net exports two measurements were made, one at the capacity t rough point where net export reaches its maximum proportional level and the other measurement was made at the midpoint where net export attains its lowest level. The error of inconsistency was determined by counting the number of quarters the cycles were off their mark. A regression analysis was then made on these errors, using the number of the cycle as the independent variable and the error as the dependent variable. The data (figures 15 & 16) clearly shows that the relationships fit within a 95% confidence interval. For the mid-capacity net export (minimum) mean was 0.714286 with a standa rd deviation ± 3.87575 quarters.The calculated z score for y=0 was determined to be -0.18425 (z=0-0.714284/3.87575) The 95% confidence interval was determined to be 3.2142≤.714≤4.3904. The trough net export (maximum) point measured a mean -0.8333 with a standard deviation ±3.50985. The calculated z score for y=0 was determined to be +0.23741 (z=0—0.8333/3,50985). The 95% confidence interval was determined to be -5.7028≤-0.8333≤4.0365. Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 15 For money supply, two measurements were also made, one at the capacity midpoint (expansion cycle) where money supply reaches the maximum proportional level and the other measurement was made at peak capacity (GNP) where money supply attains its mid-level. The data (Figure 17 and 18) clearly shows that the relationships fit within the 95% confidence level. For mid-capacity money supply (maximum) the mean was 1.0 with a standard deviation ±2.190989 quarters.The calculated z score for y=0 was determined to be -0.4564 (z=0-1/2.190989) The 95% confidence interval was determined to be 1.097≤i.0≤3.907. The peak capacity money supply (midpoint) measured a mean 0.20 with a standard deviation ±0.316228 quarters. The calculated z score for y=0 was determined to be -0.63247 (z=0-0.2/0.316228). The 95% confidence interval was determined to be -1.4395≤-0.2≤1.0365. Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 16 Interpretation of Data Theoretical reasons for these results are complex, controversial, abstract and speculative. From interpreting the data, the proposed model equation does not work well. The only variable that fits the equation in the majority of cycles is money supply. Assigning X to money supply and leaving the other variable, Y, as a blank corresponding countervailing factor works well for fitting the data and for forecasting purposes. The inconsistency of the predicted pattern of money supply and its countervailing element, interest rate (inflation rate or price level), and actual data Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 17 is a key question posed in this study. Coupling this with the observation that interest rate (inflation rate) decreases (increases) precede money supply increases (decreases) in reaching a maximum or minimum, an abstract theoretical model of 2 major countervailing elements can be established. The model’s two proposed elements: income (income efficiency) and price level (inflation rate) have in essence been observed or mentioned by both the Monetarist and Keynesian economists. Keynes establishes his General Theory on the concept of money demand as determined by income, price level and interest rates (MD=kPY + L(i)). Monetarists, on the other hand, base their theory on price level and income eliminating interest rates (MD=kPY) in accordance with Classical (Cambridge) interpretation. According to Milton Friedman: The next effect is the income and price level effect. As cash balances are built up, people’s attempts to acquire other assets raise the prices of assets and drive down the interest rate. That will tend to produce an increase in spending. Along standard income and expenditure lines, it will tend to increase business investment. Alternatively, to look at it more broadly, the price of sources of services will be raised relative to the prices of the service flows themselves. This leads to an increase in spending on the service flows and, therefore, to an increase in current income. In addition, it leads to an increase in spending on producing sources of services in response to the higher price which can now be obtained for them. The existence and character of this effect does not depend on any doctrinal position about the way in which monetary forces affect the economy. Whether monetary forces are considered as affecting the economy through the interest rate and thence through investment spending or whether, as I believe, reported interest rates are only a few of a large set of rates of interest and effect of monetary change is exerted much more broadly, in either case the effect of the more rapid rate of monetary growth will tend to be a rise in nominal income.1 From the point of view of countervailing factors and this study, Friedman’s interpretation coincides with phase 4 and 1 of the business cycle. Cash balances (savings through less spending and T-bill purchases by government) from the empirical evidence do increase in phase 4 reaching a maximum at the trough level or inflection point between 4 and 1 (Figure 10 and 11). Government policy of increasing money supply to spur economic activity in a recession has a lag effect 1 Havrilevsky and Boorman, Issues, Friedman, Milton, “Factors Affecting the Level of Interest Rates”, P.368 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 18 between policies such as buying T-bills, lowering prime rates and other measures; and its effect on the economy. The multiplier effect from increased cash balances has a lag effect during phase 1 in which bank loans increase, business and private investment increase, and debt decrease produce an increase in spending as shown in Figures 8-13 culminating in the maximization of money supply some point past the trend line or inflection point between phase 1 and phase 2. At the trend line besides debt, interest rates and inflation rate are at their lowest level, this coincides with Friedman’s observation that “the more rapid rate of monetary growth will tend to be a rise in nominal income”. A closer examination of savings and GNP (spending) in Figure 10 does corroborate Friedman’s assertions. Savings going into “peoples attempts to acquire other assets” in phase 1 depletes savings while increases spending (GNP), increases current income and increases business investment thereby increasing employment and other resources of production. Another Friedman assertion, the prices of services (labor, etc.) relative to service flows increase, implies a rise in income (income efficiency), that is, inflation and interest costs are at their lowest level while increased demand for services has a positive effect on employment. At equilibrium economist’s assume that money demand equals money supply (MD=MS) at points in time thereby determining interest rates. However, the dynamic state of the economy leads us to conclude that as price level (P) and income (Y) change throughout the cycle, money supply and money demand are also constantly changing their equilibrium point therefore establishing the prevailing interest rate. It is, therefore, easy to deduce from observations that income becomes directly correlated to money demand and money supply (with a lag effect) while interest rates and price level are inversely related. Increased income as mentioned in Friedman’s interpretation means increase demand for money (increase demand for durable goods and shifts in liquidity preference). Also in the Keynesian interpretation the relationship is apparent. The proposed model is very much mathematically idealized. Its value is in both adapting mathematically a real empirical cycle’s behavior and comparing it to the idealized model. In this idealized interpretation, income is a much more abstract variable than a real concrete measurable quantity. Income takes on the characteristic of efficiency. The precise definition and determination of income is difficult to ascertain. Intuitively, income in this context can be thought of as the attainment of goods and services by consumers at different levels of productivity, Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 19 price level, income distribution (nominal wages), employment, industrial capacity, savings, debt (satiety). That is: Income=f (productivity, price level, nominal wages, employment, industrial capacity, satiety…) Price level, also reflects measurable and immeasurable variables: inventory, interest rates, capacity, taste, demand, technology, (productivity) etc., its measurement is partially made and provided by government econometricians. That is: Price level=f (inventory, interest rates, capacity, taste demand, technology…) Figure 1 illustrates the countervailing idea of having income (Y) reach its maximum and price level its minimum at the trend line prior to GNP peaking ¼ cycle thereafter. Here income and price level represent the most efficient point in the cycle. Microeconomically, this may represent the lowest aggregate average total cost of production and least cost capacity. Conversely, ¼ cycle after GNP peaks represents the least efficient point in the cycle. Here price level change (inflation rate) is at its maximum and income-efficiency at its lowest. The best example of such an idealized cycle is found in the stagflation period of 1971-1979. Price level and interest rates reached their peak between phase 3 and 4 (Figure 5-1974) while money supply reached its lowest point toward the end of phase 4, reflecting a lag effect and confirming the precedence behavior of money demand (income) over money supply. Further evidence of the two countervailing elements in the 1971-1979 period can be seen by noting that in the 1973-79 cycle employment reached its highest level in phase 3 close to phase 4. This illustrates the inefficiency of income during this period. Although employment and capacity remained high, the price level rose reflecting high demand for an economy experiencing diminished goods and services (GNP decline). Many of the variables determining the two countervailing elements are intangible and difficult to measure. Satiety, for example is one such variable. One way of examining satiety is to determine maximum level consumer debt and savings. If the idea of a satiety point is valid them major variables reflecting satiety; savings and debt should reach peak levels together with GNP. Indeed, the pattern formed (figure 10) shows that savings is maximized both at the trough and peak. Debt, on the other hand, reaches its maximum at peak GNP and its minimum at the midpoint phase 1 and 2. Therefore, their use as a satiety indicator and income-efficiency determiners coincides with the theoretical placement of maximum income-efficiency at the midpoint (between phase 1 and phase 2), the point of least debt. And the skewed characteristic of income-efficiency at the peak where debt Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 20 also peaks in the majority of cycles other than the 1971-1979 period further substantiates the theoretical inferences. However, even with the use of these variables the intangibility of a satiety measurement for goods and services and other variables makes the task of a concrete measurement of income efficiency most difficult if not impossible to attain. One means of circumscribing such a task and determining the purported incomeefficiency variable as countervailing to price-level is a comparative study of the amount of goods and services affordable and the percentage of income spent on each by a median-wage earner working a standard 40 hour week throughout the cycle. As the median wage changes in the cycles at 40 hours/week, the percentage of income needed to purchase basic median items such as housing, transportation, food, etc. (coupled with debt capacity and savings) may be a relevant barometer of the income-efficiency concept. In a recent Time magazine article2 a comparison of purchasing power (incomeefficiency) between generations was made. The article compared the percentage of income needed for the purchase of goods and services by the father in the late 50’s and now by his offspring. A similar but more empirical study of purchasing power within a cycle may prove well worthwhile. The examination of cycles other than the 1973-79 cycle have a skewed relationship between money supply and price level change. By conjecture, they may reveal an economic paradox. It may be paradoxical that at peak GNP, interest rates and inflation peak correspondingly close afterwards thereby inversely producing the lowest income-efficiency point. The distinction between income-efficiency and real or nominal income is paramount in this analysis. While real (nominal) income may be rising for our hypothetical median 40 hour per week wage earner as business activity increases and demand for his services in turn increases his wage and output (number of hours worked), his income-efficiency for the standard 40 hours will be declining. That is, his overall (phase 2) spending will be increasing and contributing to increases in price level and business activity as purchasing power viewed from the income-efficiency concept will be losing ground. In essence, the increase in higher GNP during phase 1 will concomitantly be raising income-efficiency, while increase of GNP in phase 2 will be countered by decreases in income-efficiency. The decline of GNP in phase 3 of the cycle will in part be spurred by the decline in income-efficiency. As GNP reaches its midpoint on the downward slide, price level 2 Gwynne S.C, Time, How One California Family Has Been Caught in the Middle, Oct. 10, 1988 Vol. 132 No. 15 Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 21 and income-efficiency change magnitude. Price level is at its maximum while income-efficiency is at its minimum. Thus, in phase 4 as income-efficiency improves and price level change (inflation) decreases, GNP will decelerate to the trough because of the pull effect upward by increasing income-efficiency and declining pull downward by price level. In effect, in accordance with the model’s equation (Figure 1) at both the trough and peak the magnitude of both elements is at their half way point (X=1/2, Y=1/2). Thereby, peak and trough being created at the point where income-efficiency equals price level. Since both factors change in opposite magnitude, one increasing and the other decreasing the midpoint represents the point where one is at its maximum and the other at its minimum (either X=1, Y=0 or X=0, Y=1). In this fashion, the cycle goes full-circle propagating itself in a selfperpetuating manner. Ironically, this behavior is best illustrated in the 1971-1979 period, appropriately named the stagflation period. The inflection point for price level in this period lies at both midpoints of GNP. Most significantly, the length of time phase 3 lasts is dependent on the inflection of both income-efficiency and price level. Exogenous variables such as net exports propelled by exchange rates affect the two countervailing factors simultaneously. In phase 1, the exchange rate reflects an increase of the U.S. dollar compared to other currencies. During this period as the inflation rate and interest rate declines, the value of the dollar increases and imports increase coincidently. The depreciation of the dollar in the “ideal” business cycle model begins slightly before the midpoint of the expansionary cycle (phases 1and 2), thereby taking the cycle into phase 2, the inflationary phase. Here interest rate and inflation rate tend to increase reaching a maximum at the end of phase 3 (the GNP trend line). This causes increased export for the U.S., while imports decrease. Ironically, the net effect is increased U.S. income, contributing to decreasing income-efficiency. However, as exports increase in phase 4 the net effect is positive contributing to increasing income-efficiency as other factors contribute to decreased incomeefficiency such as lower demand for durable goods and higher unemployment (decrease in GNP). The scarcity of dollars in the world economy depleted during phase 2.3.4 and world demand for U.S. goods will have a high impact on the demand for dollars, therefore raising the exchange rate. In this fashion the cycle goes full-circle, ending up again in phase 1 with a high exchange rate and a propensity to consume imports at increasing income-efficiency and decreasing price level. As a final note, as the cycle precedes from phase to phase income and price level change relative to each other. Changes of magnitude may vary from cycle to cycle, peak inflation may reach 20% in one cycle while peak inflation may only Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 22 reach 5% in another. Income-efficiency, likewise, may change in magnitude from cycle to cycle. The period (1945-1988) of this study encompassed relatively mild and short recessions primarily caused by inflation increases and income-efficiency decreases. More protracted and severe recessions such as the Great Depression may still fit the model although income-efficiency defined by 25% unemployment, and price level defined by a deflation of prices below the cost of production; create greater weight on certain components such as government policy that as independent variables delineate price level and income-efficiency. Conclusion The preparation of this paper has been an evolutionary process. The initial ideas of aggregated averaged countervailing factors proved to be unsustainable. This gave rise to the observation that money supply and a blank countervailing variable are consistent with the proposed model and can be used for forecasting purposes. The final idealized model of countervailing factors: income-efficiency and price level change as determined by the various variables is not a new revelation. It is merely a perspective utilizing the model’s equation for cycle behavior given changes in GNP through these two factors. Also, viewed in this manner it is hoped that the model has presented a more structured analysis of the business cycle. Countervailing Factors in Business Cycles; by Augustyn J. Peretsky, M.A. pg. 23 Bibliography 1. Havrilevsky and Boorman, Issues, Friedman, Milton, “Factors Affecting the Level of Interest Rates” p.378-394 2. Gwynne S.C., Time, How One California Family Has Been Caught in the Middle, Oct. 10, 1988 Vol. 132 No. 15 3. Blinder, Alan S. , Fischer, Stanley, 1981, “Inventories, Rational Expectations, and the Business Cycle”, Journal of Monetary Economics 8 p.277-304 (Northland-Holland Publishing Company) 4. Havrilevsky and Boorman, Issues, Jordan, Elements of Money Stock Determination, p.268-287 5. Woodland, A.D., International Trade and Resource Allocation, North Holland Publishing Company, 1982 6. Hazary, B.R., The Pure Theory of International Trade and Distortions, Wiley 1978 7. Hall, R.E., Taylor, J.E., Macroeconomics, Theory, Performance, and Policy, (W.W. Norton & Company) 1986