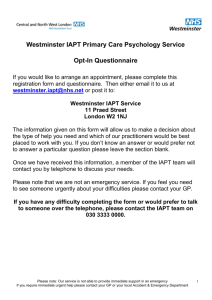

Outline of content for the IAPT Outcomes Framework

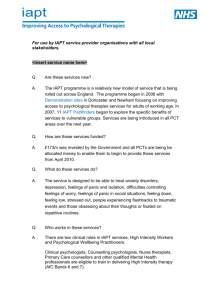

advertisement