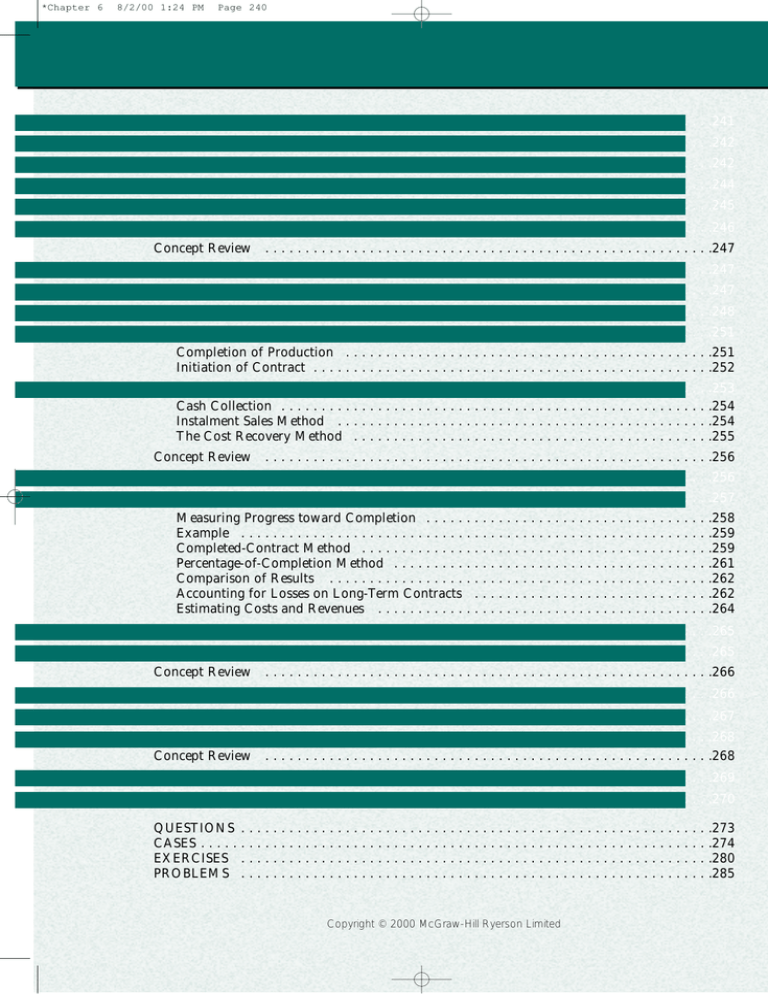

View Chapter 6, Revenue Recognition - McGraw

advertisement