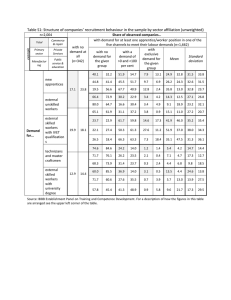

The Globalization of Labor, Chapter 5, IMF World Economic Outlook

advertisement