"white lines" at restoration margins

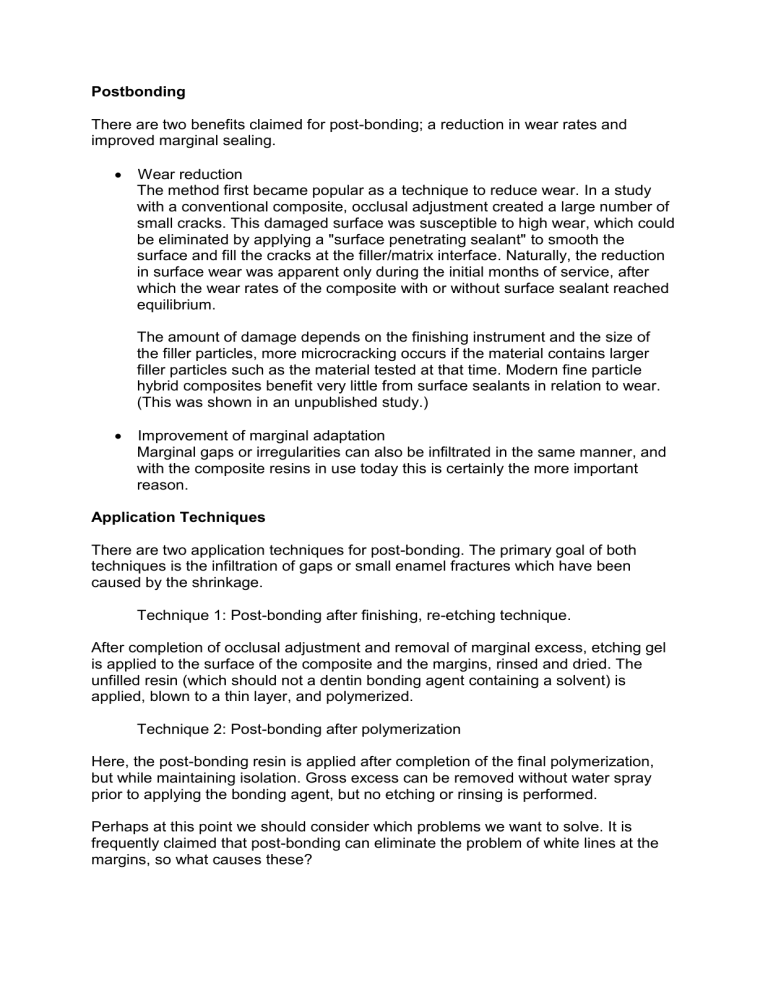

Postbonding

There are two benefits claimed for post-bonding; a reduction in wear rates and improved marginal sealing.

Wear reduction

The method first became popular as a technique to reduce wear. In a study with a conventional composite, occlusal adjustment created a large number of small cracks. This damaged surface was susceptible to high wear, which could be eliminated by applying a "surface penetrating sealant" to smooth the surface and fill the cracks at the filler/matrix interface. Naturally, the reduction in surface wear was apparent only during the initial months of service, after which the wear rates of the composite with or without surface sealant reached equilibrium.

The amount of damage depends on the finishing instrument and the size of the filler particles, more microcracking occurs if the material contains larger filler particles such as the material tested at that time. Modern fine particle hybrid composites benefit very little from surface sealants in relation to wear.

(This was shown in an unpublished study.)

Improvement of marginal adaptation

Marginal gaps or irregularities can also be infiltrated in the same manner, and with the composite resins in use today this is certainly the more important reason.

Application Techniques

There are two application techniques for post-bonding. The primary goal of both techniques is the infiltration of gaps or small enamel fractures which have been caused by the shrinkage.

Technique 1: Post-bonding after finishing, re-etching technique.

After completion of occlusal adjustment and removal of marginal excess, etching gel is applied to the surface of the composite and the margins, rinsed and dried. The unfilled resin (which should not a dentin bonding agent containing a solvent) is applied, blown to a thin layer, and polymerized.

Technique 2: Post-bonding after polymerization

Here, the post-bonding resin is applied after completion of the final polymerization, but while maintaining isolation. Gross excess can be removed without water spray prior to applying the bonding agent, but no etching or rinsing is performed.

Perhaps at this point we should consider which problems we want to solve. It is frequently claimed that post-bonding can eliminate the problem of white lines at the margins, so what causes these?

White Lines

There are a number of potential causes for white lines at the margins, which can be gaps, discontinuous voids, or microfractures in the tooth substance or the restorative material. White lines at placement frequently become black lines later, so it is certainly preferable to correct them immediately.

In general, white opacity is created by differences in the refractive index. Everyone has noticed the „bleaching effect“ when teeth are dried, this is the effect of replacing the water with air. One can see the same effect when a light curing composite is spatulated, the incorporated air lightens the shade.

For reference, the clinically relevent refractive indices are approximately: enamel = 1.7; water = 1.4; air = 1.0; and composites are in the range of 1.5 -1.6.

White lines are therefore most visible when the tooth is dry, since the difference in refractive index between air and enamel is larger than the difference between water and enamel.

Briefly, we can summarize the potential causes:

Preparation Instruments. Diamonds with a grit size over about 60

m lead to marginal enamel fractures and "derangement" of prism boundaries - small discontinuous internal cracks parallel with the prisms (Xu). Margins should be finished with 15-40

m diamond burs. Finer diamond grits cause fewer fractures, but cut more slowly: 25

m diamonds combine minimal fracturing with reasonable efficiency.

Carbide burs can produce good results if they are new, and they must also be used with minimal pressure. Carbide burs become very traumatic when dull, and should probably be used for only one or two teeth before discarding.

Preparation Angles. Undercut prisms frequently fracture during shrinkage of the composite resin. We want to avoid unnecessary overextension of our preparations, but must avoid undermining prisms. (A separate paper is available on request concerning prism orientation.)

Contamination of a shrinkage gap with blood or saliva severity of white lines, provided that the resin can infiltrate the defects. I post-bond practically every medium to large direct restoration prior to contamination (Class 2‘s prior to removing the matrix). One doesn't really need to buy a special product, any unfilled, solvent-free resin will work

– but not typical adhesives.

If you have gaps or small enamel fractures, it seems sensible to „fill“ them immediately. Once you have contaminated them with water or saliva, it is nearly impossible to to rinse anything back out of these small gaps. If you hold two glass microscope slides together and put etching gel or a dye between them, then try to rinse it back out, you will see what I mean.

These defects may have significant depth, and are probably nearly impossible to clean thoroughly if penetrated by blood, saliva, or water.

A disadvantage common to both techniques is the polymerization kinetics. If we assume that perhaps ten minutes has been required for placement, the shrinkage of the composite is approximately 90% complete, and the composite will continue to shrink during the subsequent hours.

Post-bonding may therefore seal a marginal gap, but the gap may reopen. Naturally, this will depend on the cavity size, the compliance of the tooth and restoration, and the level of initial cure.

Incorrect preparation angles

"Bonding to enamel" is primarily preparation technique. A preparation parallel to the prisms at the margin will lead to gaps, any preparation angle leaving unsupported enamel prisms at the margins generally will frequently create a white line. Prisms are

NOT at 90

to the surface, but you need to know the prism direction in order to prepare correctly.

There are all sorts of recommendations for the divergence of inlay preparations, pro and contra opinions on bevels, etc. I prefer to talk about preparation angles rather than bevels, because we need the correct angle to get across the prisms to get an etch pattern to get a stable bond. White lines are observed primarily at occlusal margins, but also at axial walls of proximal boxes in Class 2 restorations.

Occlusal Margins: On occlusal surfaces the enamel prisms intersect the cusp slope at 60

to 65

(Uribe). There is no magic angle for inlay preparations because it depends on the cusp slope: the restorative material should ideally form a 45

angle

(Note that this is not a 45

bevel from the long axis of the tooth, but rather 45

from the cusp slope). For maxillary premolars with steep cusps, an inlay preparation with a divergence of 6

may be ideal; but the same angles for a lower molar totally wrong. If the restorative material margin forms an angle over 60

you have unsupported prisms that fracture parallel with the margin. The result is frequently a white line.

Axial Margins: The simplest approximation of the prism orientation for axial margins is based on the ideas of Alan Boyd. From the occlusal view, think of radial lines from the center of the tooth. Your axial preparation angle should always cross these lines toward the „outside“; i.e. toward buccal or lingual. While not quite as accurate as the radial lines, another simple clinical guideline can be used: the remaining enamel should never form an angle of less than 90

when viewed from the occlusal (Opdam).

The development of the SonicSYS with KaVo was based on these considerations - along with some other factors. These instruments offer practically the only method to prepare the ideal axial margins for conservative Class 2's.

Application technique and materials

With the almost hypnotic emphasis on dentin bonding, enamel has practically been forgotten. Thick layers of the hydrophilic bonding agents on enamel can compromise your marginal stability. With the relatively poor strength development of these materials, the shrinkage stress of the subsequently applied restorative composite can cohesively fracture the bonding layer.

The best solution is to keep your bonding agents thin, then control shrinkage stress with your application technique (Unterbrink).

Direct restorations cusp deformation. indirect restorations

Finishing and Polishing

There is always a static intrinsic stress at the margin, and trauma during finishing can lead to stress release with microfractures. We want to use the most "atraumatic" finishing technique possible. The often repeated recommendation to finish from restorative toward the tooth is probably correct, but not that important. If we ignore dull and/or eccentric burs and bad handpieces, the biggest problem is pressure. One major advantage of discs, at least where you can use them, is that the pressure is limited automatically by the flexure. Otherwise, the best we can do is use as light a touch as possible. I use discs where I can, 15-25

m diamonds for other margins, the KaVo EVA reciprocal handpiece where access is limited, and then go to silicone rubber tips or polishing pastes.

Conclusion

If I had to "prioritize" the reasons for white lines, I would put incorrect preparation angles at the top of the list. Preparation techniques with the right instruments and correct marginal angles, controlling the shrinkage stress, minimizing finishing trauma at the margins, and post-bonding larger restorations are the keys to avoiding this problem.

If the white line has resulted from enamel fractures during preparation, one can try to postbond with a reetching technique, but the white line will probably not disappear.

(One could reprepare the margin with a small round finishing diamond, then etch and rebond, but must consider the advantages and disadvantages.

If the line is a gap due to shrinkage stress, postbonding can be done . In many such cases this is a result of intentional compromises during the preparation technique.

Since the composite restoration at this stage will still shrink further, postbonding will probably at best reduce gap formation.

Basically, no matter how careful we are, there are many little things that can go wrong; in particular at occlusal margins. Post-bonding can eliminate or reduce the negative consequences.

Dr. Gary Unterbrink

Xu HH, Kelly JR, Jahanmir S, Thompson VP, Rekow ED. Enamel Subsurface

Damage Due to Tooth Preparation with Diamonds. J Dent Res 1997; 76(10):1698-

1706

Uribe Echevarria J, Priotto Elba G, de Uribe Echevarria N. Angulacion de las vertientes cuspideas internas en relacion con las estructura adamantina y los tallados cavitarios para amalgama. Avances en Odontoestomatologia 1988; 4(4):

200-208

Boyd A. Anatomical considerations relating to tooth preparation. In: International

Symposium on Posterior Composite Resin Dental Restorative Materials. Vanherle G,

Smith DC eds. Utrecht. Peter Sculc Publishing Co. 1985: 377-403

Opdam N, Roeters J, Kuijs R, Burgersdijk R. Necessity of bevels for box only Class II composite restorations. J Prosthet Dent 1998:80(3):274-279

Unterbrink GL, Liebenberg WH. Flowable composites as "filled adhesives", literature review and clinical recommendations. Quintessence Int 1999;30:249-257

In dentin, course and fine give same margin quality

Carbides cause fractures like rough diamonds

Increased pressure does not improve efficiency of finishing diamonds

Course and supercourse almost equally efficient

Adhesive prep less invasive than conventional

Never rub etched enamel

Always prepare surface whether etched or self-etch