Study on Communicating Evaluation Results FINAL VERSION

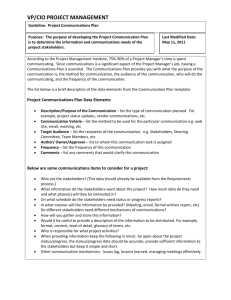

advertisement