Rights and Responsibilities - Australian Human Rights Commission

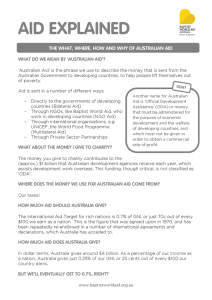

advertisement