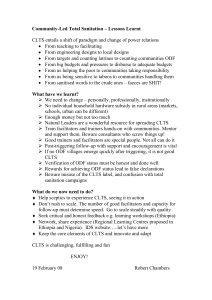

Executive Summary - Community

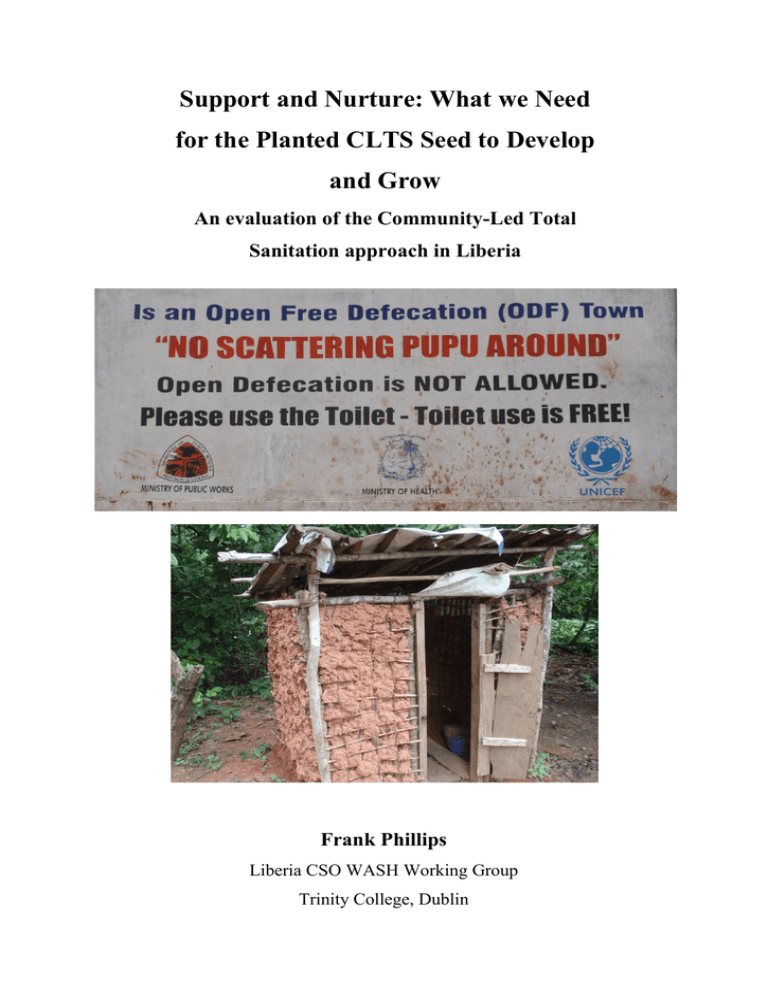

advertisement