Local Government Discretion and Accountability

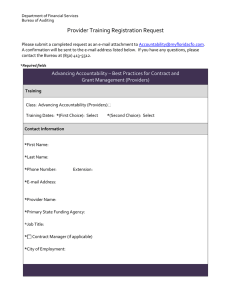

advertisement