Sao Paulo: Population and Slum Housing

advertisement

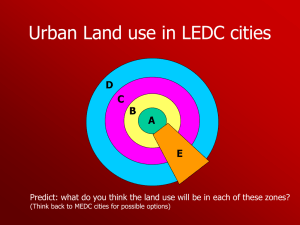

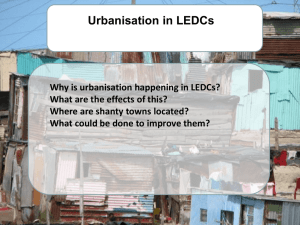

Sao Paulo: Population and Slum Housing Abstract About 32% of the world’s urban population live in slums. The problem of poor housing quality is overwhelmingly concentrated in the developing world. Sao Paulo has the largest slum population in South America. Here, urban poverty is concentrated in two types of housing, favelas and corticos. Favelas in Sao Paulo, unlike Rio de Janeiro, have developed fairly recently. Their rapid growth dates back to 1980 with their share of the population having jumped from 5.2% to 19.8% since then. Although both natural change and rural-urban migration have fallen significantly the housing problem remains immense. Urban Growth and Sprawl Figure 1: Land use in Greater Sao Paulo Sao Paulo is the largest city in the southern hemisphere and referred to by some as the richest city in the Third World. The population of the metropolitan area (2000 census) is almost 18 million (Figure 2). Figure 2: Population Growth in Sao Paulo In international terms Sao Paulo is a compact urban area. At approximately 21,000 per square mile the population density is more than twice that of Paris and almost three times that of Los Angeles. Among the six urbanised areas in the world with more than 15 million people, Sao Paulo has a smaller land area and a greater population density than only Mumbai and Mexico City. Although the city has spread considerably in the latter part of the 20th century, the issue of urban sprawl is a matter of debate. Some see it as a problem, others point to the fact that the metropolitan area covers less than 1% of the state of Sao Paulo. According to an article in Metropolis Magazine [October 2000] by Simon Romero “There is perhaps no better illustration of the dangers of sprawl than Sao Paulo with its 17 million people, 4 million automobiles and 10,000 miles of streets. The public-transportation system is woefully inadequate, its three small subway lines are saturated by 2.5 million passengers each day while an army of illicit minivans competes with municipal buses to transport twice that number along the city’s crazy-quilt of streets.” Metropolitan Sao Paulo has widened the population gap between itself and Rio de Janeiro to almost seven million [Figure 3]. Between 1991 and 2000 Brazil’s largest metropolitan area increased in population by 15.8%, as opposed to Rio’s 11.0%. All of Brazil’s other major metropolitan areas also recorded significant growth. In relative terms the most rapid growth was recorded by Brasilia. With urbanisation at the 81% level, many of the country’s social problems such as inequality, poverty and crime are urban based and require solutions in cities. Figure 3: Population of major metropolitan areas Metropolitan Area 1991 Sao Paulo 15,444,941 Rio de Janiero 9,814,574 Belo Horizonte 3,515,542 Porto Alegre 3,147,010 Recife 2,919,979 Salvador 2,496,521 Fortaleza 2,401,878 Brasilia 2,149,921 Curitiba 2,063,654 2000 17,878,703 10,894,156 4,349,425 3,658,376 3,337,567 3,021,572 2,984,689 2,952,276 2,726,556 However, the population growth rate in Sao Paulo (Figure 4) has fallen considerably in recent decades due to a combination of: • reduced rural to urban migration • a lower rate of natural increase Figure 4: Population growth rate in Greater Sao Paulo Figure 5 shows the districts of the City of Sao Paulo (10.4 million population), which generally forms the inner part of the metropolitan area. However, the City border stretches to the edge of the metropolitan area to the north and to the south. Between 1980 and 2000 the population of the central area of the City of Sao Paulo fell by 230,000, a decrease of 30.4%. In contrast, peripheral districts in the City grew rapidly. In the 1980-2000 period, the central areas population density fell from 181.5 to 110.3 persons per hectare, while the density of peripheral districts such as Sapopemba increased from 132.6 to 208.8 persons per hectare. This decentralisation trend mirrors what happened in MEDC cities much earlier. Figure 5: Population density in Sao Paulo The metropolitan area includes Sao Paulo and 39 other neighbouring administrative areas. This area accounts for almost 20% of Brazil’s industrial production. Figure 6 The vast extent of high-rise buildings in Sao Paulo Variations in the Quality of Life Although relatively prosperous in terms of the country as a whole, poverty and unemployment are huge problems. Sao Paulo has the highest unemployment rate in the country. It is also at the highest rate in recent time as the city is losing its status as a manufacturing centre and becoming a service metropolis. The process of deindustrialisation that has affected all MEDC cities is now impacting significantly on some urban areas in LEDCs. The extreme inequality in Sao Paulo was highlighted in a report in August 2002 by the city administration. Measuring each district’s quality of life using the United Nations human development index, the report found that Moema, the city’s richest district, has a higher standard of living than Portugal and is only slightly behind Spain. On the other hand, Sao Paulo’s poorest district, Marsilac, where 8,400 people just maintain a living in favelas scattered across a patch of surviving Atlantic rainforest, is worse off than even Sierra Leone, the world’s poorest country. Figure 7 The tree-lined streets of the affluent Jardins district Figure 8 A favela on the edge of central Sao Paulo Low living standards and the resulting social pathologies [crime, vandalism etc] have had a huge impact on the city in general. In 1999, Sao Paulo recorded 11,500 homicides, compared to New York’s 671. It is perhaps not surprising that the affluent elite have assembled the world’s third-largest fleet of urban helicopters after New York and Tokyo. Sao Paulo’s rich use their helicopters to hop from rooftop to rooftop to escape the squalor of the streets. Sao Paulo has 240 helipads to New York’s 10. The Changing Location of Income Groups • In the last decade or so, condominiums have emerged at the periphery of Sao Paulo because of limited space near the centre. • at the same time corticos have expanded and become more dense in the central region. • Different social groups now live in close proximity separated by walls and other security measures. For example, in Morumbi favelas coexist with luxury condominiums. The Slum Housing Problem It is estimated that substandard housing occupies 70% of Sao Paulo’s area – approximately 1500 square kilometres. Two million people, 20% of the population live in favelas while over half a million people live in converted older homes and even factories in Sao Paulo’s inner core which are known as corticos. Often whole families share a single room, which may lack electricity and plumbing. Rat and cockroach infestations are common. More than 60% of the population growth in the 1980s is considered to have been absorbed by the favelas. By the beginning of the 20th century Sao Paulo was socially divided between the affluent who lived in the higher central districts and the poor who were concentrated on the floodplains and along the railways. The rapid acceleration of urbanisation between 1930 and 1980 built on the existing pattern of segregation. However, by the late 1970s this pattern was beginning to change with growing numbers of poor migrants spreading into virtually all areas of the city. The ‘lost decade’ of the 1980s witnessed the rapid development of shantytowns (favelas) at the urban periphery, and inner-city slum tenements (corticos). Until the early 1980s, the cortico was the dominant form of slum housing when the favela broke out of its tradition urban periphery confines and spread throughout the city to become the new dominant type of slum. This happened as the newly arrived urban poor sought out every empty or unprotected urban space. It is estimated that favela residents now outnumber those living in corticos by 3:1. The rapid spread of the favelas in the 1980s mixed up the pattern of centre-periphery segregation in Sao Paulo. However, public authorities constantly removed favelas in the areas valued by the property market. The action of private property owners regaining possession of their land has driven favelas to the poorest, most peripheral and hazardous areas [floodplains, hill slopes etc]. Few favelas remain in wellserved regions, although the largest two Heliopolis and Paraisopolis (Figure 1) are located in these areas. Heliopolis is Sao Paulo’s largest slum. Established about 30 years ago heliopolis means ‘city of the sun’ in Greek. People first came to this location to play football but later they began to build shacks and the favela was established. One hundred thousand people live here in a mix of absolute and semi-poverty. Access to facilities is very limited. For example, there is one library with about 300 books for the whole community. In Paraisopolis almost 43,000 people are crammed into an area of 150 hectares near the CBD and elite residential areas. Figure 9: Extracts from the diary of an NGO volunteer worker in the Heliopolis favela November 1, 1997 – Heliopolis, Sao Paulo I am in Sao Paulo. Staying in the Batista community centre in the Heliopolis favela (slum). Heliopolis is a third stage favela, one that is well established and has been here for a long time. First stage favelas are the worst – most often crude shelters under viaducts or bridges. There is the beginnings of one along the wall of the hospital, where there are shacks along the wall, and people have planted corn and beans. Second stage are better. They are more settled looking, though they still consist of shacks that have been thrown together from whatever their builders could find. Third stage are much more substantial and permanent looking. The building material is mostly brick block. However, people are squatters in all the favelas. They do not own the land on which they have built. The streets of Helipolis are narrow and full of people and cars. There are all kinds of small businesses along the street. One guy makes a living, or tries to, cutting keys, another cutting hair. Women fix each other’s hair and give each other manicures and pedicures. There are little shops, bars and poolrooms. One bar has the interesting name of “Blue Mom”. A shop which sells just about everything is called “Uba Uba Bazaar”, which, translated, is “Hubba Hubba Bazaar”. There is not much money in Heliopolis, but there are plenty of ways of making it move around. Drugs are another way. They are said to be freely available. November 3, 1997 – Heliopolis, Sao Paulo There was a broad daylight shootout a short distance from here yesterday. It was not hard to figure that something rather awful was happening because several police cars sped by, heedless of speed bumps and sirens blaring, to a spot behind the hospital. Police helicopters did big circles overhead. At the end of it, three adults and two small children were dead. It was said to be drug related. Initially we heard that the children were caught in crossfire. Later we heard that they had been deliberately killed to distract the police, but that their killers did not get away. However, they may have been killed by stray police bullets. We will probably never know what really happened. Not long ago, two cops were ambushed in traffic on a bridge and shot. The cops then went to work and cleaned up. By the time they were finished, some seventy troublesome people had been eliminated. There is a war here. The cops are one side. The poor, who own little and have little stake in the new Brazil, are on the other. Many of the poor are organised into illicit Mafias, dealing in drugs and whatever else will sell. The justice system either does not work or works much too slowly, and is often avoided. Things are done more directly by shoot-out and cleansings. Noisy here. Busses park across the street. Bus drivers hang around and talk very loudly, even at five in the morning. And always lots of people – lots of people. People living on top of each other, people pressing against each other, always crowding, but looking past each other as they walk by on the street. Most corticos are located in the central districts – in areas that have deteriorated but near the city’s jobs and services. However, the increase in corticos in the periphery is a recent phenomenon. This has usually been due to residents building other rooms on their lot to rent out and increase income. People who live in favelas [favelados] and corticos [encorticados] do not like to be referred to by these terms, fearing prejudice in job applications and other aspects of like. The problem of slum housing affects every continent but it is heavily concentrated in LEDCs. As in the MEDCs the relationship between poverty and poor housing is very strong (Figure 7). The poor quality of housing is a considerable hazard to the safely of residents. Figure 10: Inequality, poverty and slum formation Figure 11: News report – Fire devastates Sao Paulo shantytown Saturday, December 21, 2002 Fire devastates Sao Paulo shantytown 8:11:01pm A fire destroyed great parts of a shantytown in Sao Paulo, Brazil today, authorities said, leaving one person dead and 1,115 people homeless. The fire probably started after an explosion in one of the wooden shacks of the Favela Paraguai, a slum in the eastern Sao Paulo district of Vila Prudente, Lt Eduardo Fernandes from Sao Paulo’s state civil defence told The Associated Press. The blaze then quickly spread to nearby dwellings also made out of wood and destroyed about 900 slum houses. Firemen found the body of Manoel Jose de Negeiros, 54, in a burned-down hut when they had managed to extinguish the flames after three hours, Fernandes said. Sao Paulo Mayor Marta Suplicy, visiting the fire site today, said to avoid new fires in slum areas, the cash-strapped city needed federal funds to finance housing programmes. Fires in shantytowns of Brazilian cities are frequent as many of the illegal settlements are made out of makeshift wooden shacks that lack basic safety standards and are prone to gas explosions. The Location of Favelas The location of squatter settlements is strongly linked to the city’s physical and environmental situation. A large number are found in municipal and privately-owned areas: • near gullies • on floodplains • on river banks • along railways • beside main roads • adjacent to industrial areas These are frequently areas that have been avoided in the past by the formal building sector because of building difficulties and hazards. In recent years local government has been particularly concerned with; • uncontrolled occupation close to watersheds in the southern zone (concerns about flooding and water contamination) • the rapid growth of favelas in another environmental preservation area, the Serra da Cantareira. The concerns here are the destruction of the original Atlantic forest and landslides. Figure 12: A favela on the edge of central Sao Paulo The Transformation of Favelas Initially favelas are densely packed informal settlements made of wood, cardboard, corrugated iron and other makeshift materials. Later they are replaced by concrete block construction. Often only one wall at a time will be built as a family saves up enough money to buy materials for the next wall. Then, concrete tiles with replace corrugated iron or other makeshift materials on the roof. The large scale improvements in favelas is due to residents’ expectations of remaining where they are as a result of changes in public policies in the past 20 years from one of slum removal to one of slum upgrading. Attempts to Tackle the Slum Housing Problem Over time, a range of attempts have been made to tackle the housing crisis in Sao Paulo. These include: • A federal bank (BNH) which funded urban housing projects and lowinterest loans to lower and middle-income homebuyers. • A state-level cooperatives institute (INCOOP), which helped, build housing for state workers such as teachers. • A state-level development company (CODESPAULO) for housing for low-income families and financing of slum upgrading projects. • A collaborative private sector/state company scheme (COHAB) to develop housing for limited-income families • A municipally managed COHAB for public housing construction, which also funded self-help projects (“mutiroes”) to upgrade substandard housing. During the period 1965 to 1982, over 150,000 housing units were built or upgraded, mostly through COHAB. Since the early 1980s, because of cutbacks at federal and state levels, the public housing burden has fallen more heavily on the municipality. Due to its own financial problems the number of housing units built by the municipality each year since the mid1980s has averaged less than 6000 a year. The administration of leftist mayor Luiza Erundina (1989-1992) tried to speed up public house building. Here the emphasis was on self-help housing initiatives, known as ‘mutiroes’. The city supplied funding directly to community groups. The latter engaged local families to build new or renovate existing housing. However, the annual house-building total only increased to 8000 during this period. The Rise and Fall of Projeto Cingapura (The Singapore Project) In 1992 the newly elected mayor Paulo Maluf looked for a more spectacular solution. The ambitious urban renewal plan, based on the experience of Singapore is an example of south-south technology and information transfer. The project ran from its inception in 1995 to early in 2001. It was abandoned after it had provided only a modest increase in the available housing stock. At the outset, Sao Paulo’s planners felt that the Singapore model was especially applicable because of the limited availability and high cost of urban land in both cities. • • • Most housing blocks were built next to slum housing whose residents were to receive priority. Early buildings were low rise, with higher buildings preferred as the project advanced. When built, ownership passed to the municipal COHAB, which collected rents (R$57.00 per month). • • • Each new project was assigned a social worker to oversee the transfer of families from favela to temporary settlements to new housing unit. Landscaping and leisure areas were included in the layout of developments. A criticism has been that no provision was made for small-scale businesses within the projects. While there was general encouragement for the initiative a range of problems resulted in only 14,000 units being constructed as opposed to the 100,000 planned.: • Only a fraction of the proposed funding was made available • The unit cost escalated sharply • Once buildings were occupied, residents began to identify serious quality of life issues. Living space was widely seen as inadequate. • Although rents were set modestly they proved beyond the means of many who fell behind with payments. A New Strategy The election of socialist mayor Marta Suplicy in 2000 marked a change in strategy towards the housing issue: • The new administration promised to spend $R3 billion on housing during its term in office. • The 1000 unfinished Cingapura housing units were to be completed. • The new strategy would be designed to obtain maximum impact for minimum cost. The concept of the mutirao [self-help scheme] was resurrected, assisting families in self-construction or upgrading of their own homes. • The house unit cost of self-hep schemes is between $R11,000 and $R15,000 compared to over $R20,000 for housing units in the Cingapura Project. A flagship scheme to alleviate poverty in favelas is under way in Santo Andre. Figure 13: Social inclusion in Santo Andre, Brazil Santo Andre, with a current population of 650,000, is part of the Sao Paulo Metropolitan Area. Santo Andre has been undergoing a period of transformation, from its industrial past to an expanding tertiary sector. The economic gap between the rich and poor has grown, exacerbated by the slowdown of the Brazilian economy during the 1990s. As a result, living conditions have deteriorated and a number of favelas – areas of extreme poverty – have emerged. The municipality is promoting an integrated Programme of Social Inclusion as a strategy to alleviate poverty. The objective of the programme is to establish new ways of formulating and implementing local public policies on social inclusion. Fourteen principal partners, local, national and international, are actively involved in the programme. Four areas were chosen for the pilot phase, selected through a participatory budgeting process, resulting in a total amount of US$5.3 million, which has been invested in the provision of urban infrastructure and services. The project has seen the improvement of basic services in some of the worst neighbourhoods. Micro-credit facilities have been made available to smallscale entrepreneurs, while health care has been made more accessible through community health agents. Other social programmes have been implemented including literacy campaigns for adults and programmes aimed at street children. Recreational facilities have been made available, serviced plots have been transferred to families and low-income families re-housed in apartment buildings. An index has been developed to measure social inclusion and data collection is carried out on a regular basis. One of the most important results has been the engagement of a wide range of actors and the creation of effective communication channels. All activities have taken account gender participation and mainstreaming. The administration intends to extend the pilot programme to all slum areas in the city, through differentiated slum upgrading projects, while strengthening the approach towards regularisation of land tenure. In addition, the programme will attend to all families facing situations of extreme economic exclusion through a revised minimum income policy and through the up scaling of existing programmes. Three initiatives from Santo Andre on Good Governance, Traffic Management and Administrative Reform are featured on the Best Practices database. The effective reduction of urban poverty and social exclusion in Santo Andre is based on a number of key principles: • • • • • • Well targeted government interventions in the urban sector can foster citizenship and enable people to create more urban livelihoods The active participation of the urban poor in decision-making promotes effective formulation and implementation of local action plans The participatory budgeting process, an innovative approach to urban governance and decision-making provides a real voice for the urban poor in both the allocation and use of municipal and other resources The Municipality of Santo Andre has shown that while effective leadership needs to be ensured by the local administration it, in turn, needs to be devolve decision-making and implementation powers to the community Inter-agency collaboration and effective channels of communication between various actors and stakeholders is critical to successful slum improvement and reduction of poverty and social exclusion Principles of equity, civic engagement and security are key to success. Figure 14: A favela on the periphery of Sao Paulo with high-rise buildings in the background Occupation of Buildings by Homeless In July 2003 more than 4,000 homeless people occupied four abandoned high-rise blocks in the centre of Sao Paulo. Police prevented the occupation of two other buildings. This occupation and others was organised by ‘Movimento Sem Teto do Centro’ [Movement of Roofless in Centre]. This organisation is protesting about the poor record of the authorities in tackling the homeless problem. They are also angry about the way street sellers are treated, with the authorities confiscating their goods because they are trading without licenses. For many homeless families and others, street selling is their only source of income.