Expanding the capacity to learn of student teachers in

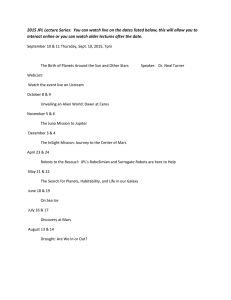

advertisement