Standards of Practice - Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy

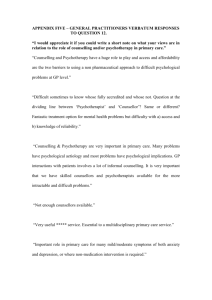

advertisement