FINANCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DONORS AND RECIPIENTS IN THE NON-PROFIT SECTOR

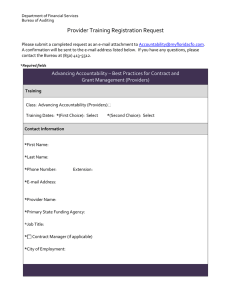

advertisement

FINANCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DONORS AND RECIPIENTS IN THE NON-PROFIT SECTOR John Gourdie and Judie Rees School of Business and Administration, The Waikato Institute of Technology Abstract The issue of accountability in the non-profit sector and its subset of charitable entities is an important and emerging area of research. This paper reports on interviews held with the managers of three charitable entities operating in the Waikato area to determine the level of accountability each required from their grant recipients. Two of these charities were Community Trusts, the third was a gaming charity. This study suggests that, while accountability requirements in this sector differ from the requirements of a business model, different stakeholders within the sector also have different accountability requirements. These differences appear to depend, to a considerable extent, on the closeness or distance of the relationship between provider and recipient. Keywords: charity, accountability, non-profit, donors Introduction The issue of accountability in the non-profit sector and its subset of charitable entities is an important and emerging area of research. Internationally, evidence suggests that non profit organisations play an increasing role in national economies (Cribb 2004; Salamon 1998; Flack &Ryan 2005) A number of developments have occurred in New Zealand in recent times that focus on charities and the issue of accountability. The new Charities Act 2005 establishes the Charities Commission; the Commission has a function of educating charitable organisations about matters of governance and management and stimulating and promoting research about the charity sector (Charities Commission 2006). The government implemented a joint initiative in February 2005, for the formation of an advisory committee for the study of the New Zealand non-profit sector. This initiative recognizes the importance of the overseas research projects initiated by Johns Hopkins University and in particular Lester Salamon (Office for the Community & Voluntary Sector 2005) and the need to similarly recognize the importance of the non-profit sector in this country. Also, the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants has produced a report from its taskforce investigating non-profit issues. This report calls for an increased involvement by accountants with the non-profit sector and in particular the need to undertake leadership and educative roles (NZICA 2005). These recent government and professional initiatives point to the importance of the non-profit sector and the timeliness of undertaking research into financial accountability issues in this domain. Aims This paper initially considers what is meant by the term accountability and reflects on the current call for increased accountability from charitable entities. Preliminary findings from a study of financial accountability relationships between donor organisations and non-profit sector grant recipients are then presented. The study was prompted by media reports that some local community organisations, having failed to account properly for grants they received, were to be declared ineligible for further grants (This Week, Hamilton, 2005). This state of affairs suggests a need for improved financial accountability by local non-profit organisations to the donor organisations that fund them via charitable grants. The aims of this study are, therefore, to contribute towards (i) identifying the issues and challenges in accountability relationships between charitable donors and recipients and (ii) identifying those key areas where theoretical expectations and actual practices diverge. Background What is meant by accountability? Cordery & Baskerville- Morley-Morley (2005, p2) suggest that within the charity sector there exists a “failure to establish a widely agreed definition of accountability”. These authors are critical of a simple stakeholder analysis that assumes all stakeholders have similar accountability needs. Their research identifies the complexity of the charity sector and calls for a more contextual approach in defining accountability relationships. Using the research of Hayes (1996) they delineate charities by typology. Types of charities range from service providers and pressure groups to mutual aid providers. The implication here is that a complex range of stakeholders exist with different accountabilities - “We suggest that, in fact accountability needs to be more clearly identified with the different stakeholder groups” (Cordery & Baskerville- Morley, 2005:9). The Hayes 1996 classification of charity accountabilities is well established in the charity literature and is defined as • Fiscal accountability (ensuring the funding has been spent as agreed, according to the appropriate rules) • Process accountability (ensuring proper procedures have been followed to provide value for money) • Programme accountability (providing assurance that the charity is effective in achieving results intended) • Accountability for priorities (fulfilling user needs appropriately). D:\219549058.doc 2 The Cordery & Baskerville- Morley- Morley research clearly reiterates the early accountability findings of Hyndman (1990), where a call is made to shift the emphasis from financial to non-financial disclosures. This call has been answered by both academics and the profession. In New Zealand, the accounting profession has provided an instrument for wider accountability reporting through the Statement of Service Performance, although this appears to be little used (Thompson 1995). Call for more accountability Some New Zealand literature exists on accountability in the charity sector. Both the Property Law and Equity Reform Committee (1979) and the Working Party on Charities and Sporting Bodies (1989) as reported by Newberry (1994) recommend increased accountability requirements. Newberry (1992 & 1994) reports on accounting requirements and practices of charities in New Zealand. A significant finding of her research was a need for greater accountability and a call for increased government regulation and self regulation by the charities themselves. Part of Newberry’s research investigated comparative international regulatory requirements and made the observation that New Zealand imposes comparatively few accountability requirements on charitable organisations. The Accountability of Charities & Sporting Bodies Working Party, an ad hoc working party under the auspices of the New Zealand Association of Philanthropic Trusts, produced a report in April 1997. This report identified a lack of accountability requirements and promoted a position of increased self regulation. Survey research was undertaken to determine the views of a number of sporting and charitable bodies and respective stakeholders. The results of this survey generated the desire for increased self regulation (Accountability of Charities & Sporting Bodies Working Party 1997) This Accountability of Charities & Sporting Bodies Working Party report identified the Consumers Institute as an organisation interested in the activities of the nonprofit sector (p.6). This organisation has on a number of occasion’s advocated increased regulation and in particular the creation of the Charities Commission. “Incredibly, there is no official regulation of charities…..This will change if, as expected, the government establishes a Charities Commission in 2004.” Consumers Institute (2002) Since the 2005 introduction of the Charities Act, Baskerville 2006 has identified commonalities in recent dishonest practice problem areas in non-profit organisations in New Zealand and has pointed to the potential for the Charities Act to reduce the occurrence of such activities. In addition to these NZ discussions of non-profit sector accountability, overseas studies have raised similar issues of concern. US studies, for example, indicate that fraud exists with considerable frequency in the non-profit sector and appears to be increasing at an alarming rate (McNeal & Michelman, 2006). Prominent D:\219549058.doc 3 frauds in this sector have raised the attention of the US Senate Finance Committee with the appointment of the Panel on the Non Profit Sector (Strom 2005) The Panel has made a number of far reaching recommendations including calls for increased accountability, best practice and provisions similar to the Sarbanes Oxley Act. A debate now exists and centres on what is the appropriate reaction to this increase in fraudulent activity. Should non-profit organisations face the same governance standards required of business organisations? Floch suggests that an entire industry has emerged. “Could anyone have envisioned that an entire industry devoted to such concerns would spring to life? That seminars articles, research, training tools and studies would develop” (Floch, 2006:2). Salamon and Geller (2005) conducted a US wide survey of non-profit organisations and concluded the breakdown in accountability is significantly exaggerated. The recent US literature therefore reflects a tension between those seeking increased rules, governance and accountability and those who suggest the situation is overstated and call for caution in increasing regulation. This review of the non-profit sector accountability literature provides a background to our empirical study of charity organisations that make grants. We are examining what might be described under Hayes classification as the fiscal and process accountability requirements of three New Zealand charities. Our aims are to identify the issues faced by current charities in respect to accountability and to place the issues within the literature dialogue. This literature dialogue suggests accountability problems may exist and calls for contextual approach in defining accountability relationships. We use a New Zealand contextual situation to reflect on those areas where expectations and practices diverge. Method Interviews were conducted with senior staff members of prominent donor organisations in the Waikato area. These staff members were asked to comment on: their financial accountability expectations of grant-receiving organisations; procedures and control mechanisms used to secure appropriate accountability by grant recipients; their perceptions of where accountability practices fall short of requirements; and what steps they consider necessary to reducing this performance gap. A semi structured interview schedule was used, which included a series of nine questions (See Appendix A). All questions were presented to the interviewees as Powerpoint slides prior to the interview; this allowed interviewees time to consider their responses in advance of the interview. Typically interviews lasted between 40 minutes and 1 hour. Clarification of any unclear issues was achieved via follow up telephone conversations. Two interviews were taped and transcribed. Sensitivity reasons prevented the third interview form being taped however extensive notes were made during this interview. D:\219549058.doc 4 All three organisations make grants in the community. Table One indicates the size of the grants made in 2005. Table One Organisation C1 C2 C3 Total Grants Allocated in 2005 $ 3 million 13 million 8.7 million Findings The charity accountability environment The managers interviewed all acknowledged particular characteristics of the nonprofit sector. All recognised the importance of non-profit organisations in enriching local communities with the activities they perform. This was described by one manager “the vast majority of community organisations out there are doing a good job and making a small amount of money go a huge distance” (Interviewee,C3,2006) The voluntary nature of the non-profit organisation participants was acknowledged and with this was a desire by the charity donors not to impede volunteers in their activities, in particular, with unnecessary or burdensome accountability tasks. “reality is, not everything can get done, you’re getting you know, people who are doing things on top of their daily work, on top of bringing up families, on top of all that stuff, and then suddenly you’ve got to complete another bloody form for the C1 application” (Interviewee,C1,2006) “you know, there’s a level at which you just become.....you almost effectively block all applications by making the rigmarole and the red tape too hard. “(Interviewee,C1,2006) This suggests that accountability acts as a barrier or burden to non-profit organisations. If the accountability requirements are too difficult then volunteer community work will not be carried out. This theme is reiterated in the fact that all three charities do not undertake an audit to ensure that recipients spend the grant as they have proposed. The rationale for not carrying out an audit is one of cost benefit. To undertake a genuine audit and ensure monies have been spent correctly would involve considerable cost. The cost of the audit would not justify the benefits gained and in particular the reduced benefits available to recipients if monies were spent on auditing expenditure. Hayes (1996:111) identifies the issue of the cost of accountability “while the independence of voluntary agencies is not greatly threatened by demands for accountability, the associated costs in D:\219549058.doc 5 complying with this requirement may pose problems”. The charities concerned seemed acutely aware of the real costs of imposing stringent accountability requirements that potentially erode the donations that could be provided. One manager explained the situation as follows: “So, a proper audit would be us going out or getting a competent person, you know, independently qualified, and saying....confirm that this is as per their thing....that would be just extraordinarily expensive” (Interviewee,C1,2006) “ You know if you’re applying for $5000 and you’re having to get $1000 worth of accountancy, quantity surveyor , engineering report type things; people will say oh sod it, we wont bother applying” (Interviewee,C1,2006) This would suggest the calls for increased accountability (Baskerville, 2006) should be tempered and balanced with voice from the sector that points out increased costs will impinge upon non-profit organisations’ ability to perform. Malloy (2006:67) when referring to the vital role of volunteers in non-profit organisations states “An increasing amount of time is being spent on administrative processes to comply with legislation and other reporting accountabilities. The cost of this detracts from the benefits that volunteers would otherwise provide directly as service to their communities. While it is important to recognise the need for accountability it is also important to value what volunteers do as an integral part of communal strength and resilience” The dual complexity of the accountability relationship (Hayes 1996) was identified in our interviews. This centres on the requirement of grant recipient organisations to potentially provide accountability to donors who provide resources and to clients and members who receive services. The managers indicated and accepted that recipients clearly saw their prime accountability responsibilities to clients and members and not to funders. This view was put clearly by one manager “our C3 absolutely understands that the community organisations see themselves as accountable first of all to the community they serve not to funders.. so while we think they are accountable for the money they get we also understand that their prime accountability is to the communities they serve” (Interviewee, C3,2006) The tax charitable status clearly impacts on accountability issues. For one organisation grants are clearly recognised as donations and legal gifts. There is clearly an understanding that a contracting process is not taking place and legally the return of grant money cannot be demanded. This legal situation was explained by one manager “donations are unconditional gifts so they are very much not contracts….legally they are an unconditional gift and you are on legally tricky ground to ask for that back” (Interviewee, C3,2006) D:\219549058.doc 6 This legal interpretation has impacted in limiting the accountability regime implemented by charity 3. “so while we think people are accountable for the way they use our donations we don’t do the kind of accountability , financial accountability, that the District Health Board and the kind of auditing that would happen there” (Interviewee, C3,2006) This suggests that charity 3 does not see accountability in a legal sense. The inference then is that the accountability processes adopted by the charity will be contextually different to the accountability models used in a business context. The degree of close community involvement reflects on how each charity sees accountability. Two of the organisations (C1 and C3) have close links to the Waikato district and very much regard themselves as local community funders. The third organisation (C2), a gaming charity, provides grants to recipients throughout New Zealand. The strength of relationship with the local community and the power of an external stakeholder provide a point of difference in their view of accountability. This contextual difference is important and fulfils the need identified by Cordery & Baskerville- Morley (2005) to identify different stakeholder groups; the implication being that different stakeholders will have different accountability needs. Local Community Funders – Accountability The environment of local charity funders presents unique accountability issues. Funders appeared reluctant to impose onerous accountability obligations on already busy volunteers who have different accountability priorities. Furthermore the implication that the grants are legally donations or unconditional gifts, makes a strict business like accountability problematic to administer. These factors have created what might be called a ‘close’ working accountability relationship. Central to the relationship is knowledge and involvement in the local community. Managers interviewed explained how both employees and directors interacted with the community. Both charity funders indicated a strong relationship with their recipient community. Visits are undertaken by charity staff and in particular members of the charity were invited to inspect and see the projects that had been achieved. This creates a form of social accountability, as expressed by one manager “We visit most organisations .., we have two donations advisors .and over a rolling year cycle we would speak and visit to most organisations.. So that’s a form of accountability I guess Not that we go out and say show us how you have spent that money although that is what most people tend to do” (Interviewee,C3,2006) D:\219549058.doc 7 Another manager expressed a similar view “now a number of trustees actually go out and visit granting applicants, number of us do that, typically it’s the opening of the such and such you know its a gala type affair, we don’t go out there with the purpose, but you go out there and you see that the tennis courts are up and you see that the painting is on the wall” (Interviewee,C1,2006) A consistent theme identified by the interviewees was the frequent change of personnel and change of residence for many of the recipient organisations. These changes in personnel place particular difficulties on ensuring accountability requirements are met. “Particularly in (Interviewee,C3,2006) small organisations, people change all the time” “you’d ring and ring and ring the person who was the president of the....or you know, the treasurer, the secretary and she’s not here any more, she’s now living with her family in Rotorua, and you know, you get a new committee, and to what extent do you hold that committee responsible for the downfall of the previous committee” (Interviewee, C1,2006) This is an indication of how accountability is operating at a very personal, individual and trust based level. This reiterates the concept of social accountability, that uses ‘close’ personal relationship and in a sense the requirements of accountability come under pressure when recipient organisations change personnel. The accountability relationship is initially developed by the use of funding application forms. Both local funders place considerable importance on funding application documentation. This requires applicants to provide constitutional documentation, financial statements, budgets and quotes. For one charity funder, if the applicant had received previous grants, then documentation to substantiate previous expenditure was required with the new years application. For the other funder an accountability declaration form was required. In both cases this accountability information was required for ongoing funding. A failure to provide the information was regarded as a breach of relationship and would result in the unlikely payment of a further grant. This was expressed by one manager as “how we actually see accountability, first of all we want to operate on trust, absolutely, but how we also see it is that we will hear if something is going astray and the main way we have of responding to that by C3 is that the organisations are unlikely to get donations the next year” (Interviewee,C3,2006) D:\219549058.doc 8 Grants to organisations applying for the first time are made with a sense of trust. These grants are likely to be small and the concept of materiality applies. To establish ongoing funding however, the grant recipient would need to comply with the accountability documentation requirements. Operational staff in both local funders appeared to go to considerable effort to follow house rules and procedures to ensure accountability requirements are complied with. The accountability requirements of recipients who have received large grants is much more rigorous and requires a formal reporting procedure often by way of personal presentation from members of the recipient organisation. Both local funders noted that grant monies were often returned from recipients when situations altered with respect to the funded project. This was seen as part of the ongoing relationship necessary for accountability. Gaming Charity - Accountability One charity donor investigated derives income from gaming and can be described as a gaming charity. Charities deriving income from gambling come under the auspices of the Gambling Act 2003. One of the purposes of the Gambling Act is to “ensure that money from gambling benefits the community” (New Zealand Government, 2003:10). Within the Act are provisions that call for the gaming charity to perform an “annual review of the criteria, methods, systems, and policies it uses for considering the distribution of net proceeds from class 4 gambling” (New Zealand Government, 2003:89) The Gambling Act makes the Department of Internal Affairs a powerful stakeholder in the affairs of gaming charities, through its requirement to audit these organisations. This donor organisation (C2) had more rigorous accountability requirements than the other organisations studied. This seems to be as a direct result of the more stringent requirements of the Gambling Act 2003. Although the Act was passed to “more strictly regulate licensed gambling” (Secker, 2005) its passing has led to more rigorous accountability requirements, both for the organisation and its grant recipients. All aspects of C2’s activities are subject to audit, including both the grant application process and the payment of grants. These are spelled out in the Gambling (Class 4 Net Proceeds) Regulations 2004 (relating to gambling in pubs and clubs).The Department of Internal Affairs provides checklists to assist organisations in meeting their audit requirements. The manager sees achieving audit compliance as essential, “otherwise our licence is at risk” (Interviewee, C2, 2006) Under s.58 of the Act, failure to comply will result in, at best, six months licence suspension; at worst, licence cancellation D:\219549058.doc 9 To achieve this compliance, it is imperative that grant recipients’ accountability requirements, as set out in the Act and the Regulations, are also met. S.117 (1) (b) gives the Secretary of Internal Affairs the power to investigate and audit a grant recipient. The C2 application form requires that “records, invoices and/or receipts, relating to the grant, are kept in a separate file” and will “be made available for inspection by the Department of Internal Affairs and/or the [organisation’s] auditors on demand”. In accordance with the Gambling Act 2003 and its accompanying regulations, adequate documentation must be used and supplied by grant applicants. Included in this documentation must be comparative quotations or other evidence of the costs of the proposed undertaking. This requirement has meant that grant applicants have had to “clean themselves up” (Interviewee, C2, 2006) The manager has seen “a dramatic improvement in accountability” (Interviewee, C2, 2006) as a result. In granting funding, the donor organisation places extreme importance on the credibility of the applicant. (This credibility requirement is similar to the other donors in the study.) In addition to the quotes or other evidence required by the Act, financial statements (preferably audited) and minutes of at least the last two meetings must be included with the application form. These are reviewed by C2 staff to “determine the sustainability of the [applicant] organisation” (Interviewee, C2, 2006) Importance is placed on the applicant having internal structures in place to ensure appropriate financial procedures will be carried out in relation to the grant. The “calibre of the applicant’s committee members” is also taken into account, where possible. (Interviewee, C2, 2006) Applications are cross-checked against IRD donee lists to establish charitable status. In common with the other organisations studied, C2 outlines its accountability requirements in the application form and again in the letter to successful applicants. The organisation also encourages prospective recipients to make contact to discuss their proposals prior to the approval process. As well as giving staff the opportunity to learn more about the organisation, its people and the activity for which funding is sought, this gives an opportunity to discuss the accountability requirements. Successful applicants must produce invoices within six months of receiving their grant. Checks are made on all recipients after six months to ensure appropriate accountability returns have been made. Non-compliance earns the recipient “a black mark. They won’t be considered for new funding grants.” (Interviewee, C2, 2006) D:\219549058.doc 10 The increased level of accountability required by this organisation has had a downside. “Some applicants now can’t get through the system” (Interviewee, C2, 2006) because they find the form-filling difficult. Interestingly, another interviewee commented that her organisation is now being inundated with “great wads of invoices that weren’t needed in the past” (Interviewee, C3, 2006), probably in response to the greater accountability required by the gaming trusts. Another significant area of difference in the operations of this organisation is that the sense of “community” is not as strong. The organisation in fact serves a number of communities in both the North and South Islands, as the majority of grants must be made in the community where the organisation’s funds were generated. The trustees who approve the grants are not representative of these communities. In fact, most of the grants are made to South Island communities but the four trustees are from the central North Island and do not have the involvement evident in the trustees of the other organisations in this study. The accountability requirements of C2 illustrate a number of aspects discussed in the charity accounting literature. First, they would be classified under the Hayes (1996) classification model as Fiscal Accountability. The Department of Internal Affairs sets down rules that must be followed by both the charity and the recipient. Newbury’s (1992, 1994) call for increased government regulation has been responded to by the increased accountability required by the Gambling Act 2003. It is our view that perhaps this increased regulation was designed to increase the accountability of the funder rather than the recipient, but this aspect of accountability is outside the scope of this paper. The end result has been that the accountability of grant recipients has increased. Cordery & Baskerville- Morley’s (2005) position that there are a range of accountability needs is supported. The sensitive nature of C2’s source of funding revenue (gaming proceeds) has had an impact on the level of accountability required. Also, because of the lack of relationship between funder and recipient, processes to ensure accountability assume more importance than the requirements of the other funders in the study. Problems All three charities indicated that no current problems existed in their accountability arrangements. This replicates the literature dialogue from the US (Salamon and Geller, 2005) that identifies a tension between those seeking additional accountability (Baskerville, 2006) and the charities who do not perceive a problem. The nature of problems differs again between the local funders and the gaming charity. The local funders noted that small problems had occurred in the past where fraud had occurred in the recipient organisation. Some effort was made to recover funds and restrictions were placed on further funding. In one fraud situation identified, the essential theme seemed to be ensuring the fraudulent organisation had recovered and was operationally sound; once assured of this the charity funder was eager to establish relationship and provide urgently needed funding. D:\219549058.doc 11 For local funders, it is important to note the interesting difference between (i) what would seem to be a minimal accountability environment in terms of our normal (business-orientated) expectations of reporting, monitoring, audit etc. and (ii) the organisations’ views that accountability is operating well. This again reiterates how local charity funders see accountability operating in ‘close’ working relationships; as long as the close relationship is working well, there is perhaps less need for the formal (more distant) business accountability mechanisms. This may well represent the different contextual stakeholders identified by Cordery & BaskervilleMorley, (2005). This point is can be observed in the increased accountability arrangements of the gaming charity. Relationships with recipients are more distant for a number of reasons. Recipients are geographically located across the country, trustees do not have close relationships with many of the recipients and the Gambling Act imposes additional accountability requirements. This suggest different stakeholders with different accountability needs Regulation 12 of the Gambling (Class 4 Net Proceeds) Regulations 2004 requires the donor to make its “best endeavour” to recover money distributed to a grant recipient if it transpires that the recipient was double-dipping, or if it has not used the money for the specific purpose for which it was distributed. To assist in detecting double-dipping C2 has collaborated with three other gaming trusts to set up the GML (Grant Monitoring Ltd) database. Each organisation enters details about the applications it has received; enabling a check to make sure the applicant has not approached the other organisations for funding without disclosing this on the application form. GML intends to expand its scope, inviting other donor organisations to become part of the operation. The implication again is that increased accountability mechanisms are required where close relationship is not present. For C2, minor problems have been experienced where it has been found that grants have been used to fund retrospective purchases (not permitted in the Authorised Purposes) or on items not included in the original application. Monies spent in this way must be reimbursed to the donor. Follow-up letters are sent to any recipients who have not met the requirements. If a recipient fails to comply, return of the grant is requested and debt collection agents are used if necessary to recover funds. D:\219549058.doc 12 Conclusion This study conducted interviews with senior staff members of three charity donor organisations in the Waikato area. A semi structured interview was used to investigate each organisations view of recipient accountability and the mechanisms used to achieve this accountability. The findings contribute towards enriching our understanding of non-profit organisations and addresses the call made to undertake research in this important area of economic activity (NZICA 2005) This study has its own set of limitations. The study is limited to three organisations in the Waikato area of New Zealand; as such, the organisations are not broadly representative of charity donors in New Zealand. The study observed only the accountability relationship between charity donors and recipient organisations. We acknowledge other accountability relationships exist in particular the accountability relationship between charity donors and their wider constituent stakeholders; this is beyond the scope of this paper. Environmental issues observed suggest delineation between the donor charities. We observed local charities that provide donations strictly in the local area and a gaming charity that makes donations across the country. For both types of charity the accountability practices do not appear to operate in the same way as we would expect in a business context. On the surface this would suggest accountability is weak and supports the argument of Baskerville (2006) that additional accountability may be necessary. The research findings however suggest that viable accountability mechanisms exist that are sufficient to meet the perceived needs of funders (who don’t see problems with accountability), yet are still cost effective and practical. These accountability mechanisms differ for each type of charity. The mechanisms can be described as social in application and centre on stakeholder relationship and the degree of distance or closeness in the relationship. For local funders a close working relationship is established with the recipient. Accountability here is linked to an ongoing relationship. The gaming charity has a more distant relationship with its recipient stakeholders. These stakeholders are often unknown and geographically distant; furthermore the requirements of the Gambling Act 2003 create a distant but powerful stakeholder that is able to impose greater accountability requirements much like those seen in the business sector. D:\219549058.doc 13 References Accountability of Charities & Sporting Bodies Working Party, (1997). Consultation Report on the Accountability of Charities and Sporting Bodies. Baskerville, R. (2006). What mischief does this legislation seek to cure? Chartered Accountants Journal,85(5), 38-39. Charities Commission, (2006). A Guide to the Charities Act. Cordery, C. & Baskerville-Morley, R. (2005). Hegemony, Stakeholder Salience and the Construction of Accountability in the Charity Sector, Working Paper Series, 25. Cribb, J. (2004). Paying the piper - Voluntary organisations and accountability. Paper presented at ANZTSR Conference. Consumers Institute. (2002) Child Fundraisers. Retrieved from http://consumeronline.resultspage.co.nz/display.php?p=Q&ts=custom&w=charities &cmdSearch=Search Retrieved 21/7/06 Flock, J. (2006) Not-for-Profit Governance: Too Much or Not Enough? The CPA Journal. 76 (1), 80. Flack, T. & Ryan, C. (2005). Financial Reporting by Australian Nonprofit Organisations: Dilemmas Posed by Government Funders. Australian Journal of Public Administration. 64, (3), 69. Hayes, T. (1996). Management, control and accountability in nonprofit/voluntary organizations. Aldershot ; Avebury. Molloy, A. (2006). The vital role of volunteers. Chartered Accountants Journal,85(5), 6667. Mueller, J., Higgins, A., Tau, M. & Harshada, P. (2004). When being committed to the cause is not good enough: The looking glass evaluation tool as a credible performance measuring tool for non-profit organizations. Mueller, J., Higgins, A., Williams, D. & Tau, N. (2004). The measurement of responsible governance and management of NPO's in New Zealand: An evaluation tool for NPOs, Donors and Government. “If you have no money – You have no mission”. Corporate Governance: International Journal of Business in Society, 5 (2). Newberry, S. (1994). Charity accountability requirements. 73, (7), 32 Newberry, S. (1992). Report on Special Issues of Accounting for Charities in New Zealand. Coopers and Lybrand Peter Barr Research Project. New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants. (2005) Report on the Not–for–Profit Taskforce. Office for the Community & Voluntary Sector. (2005) Understanding the non-profit sector: improving information and measuring contribution. Office of the Auditor General. (2003) Inquiry into public funding of organisations associated with Donna Awatere Huata MP Salamon, L. & Geller, S. (2005) Nonprofit governance and Accountability The Johns Hopkins Centre for Civil Society Studies, Communique No 4,October. Salamon, L. (1998). Holding the Center: America's Nonprofit sector at a Crossroads. Nathan Cummings Foundation. New York. Salamon , L. (1998). Johns Hopkins-led Study Finds Nonprofit Sector is a Burgeoning, Economic Force, Retrieved May 20,2005 from http://www.jhu.edu/news_info/news/home98/nov98/nonprof.html Secker, A. (2005). Press Release, Department of Internal Affairs, 30/8/05 Strom, S. (2005). Charity Panel Urges Oversight and Accountability Increase New York Times June 23 p16 This Week 2005 Hamilton D:\219549058.doc 14 Appendix A Semi Structured Interview Questionnaire: 1 Background information: i) Name: ii) Age of organisation: iii) Objectives of organisation: (focus of grants) iv) What publicity is used to notify prospective applicants of the grants that are available? 2 Is a grant application form used? 3 Does your organisation have financial accountability requirements from successful applicants? i) What are your financial accountability requirements? ii) Do they vary for the size of the grant? (timing?, multiple reports or final report) iii) Why do you have financial accountability requirements? 4 Are financial accountability requirements outlined in the application form or other documentation? 5 Are the financial organisations? 6 Is a vetting process (re applicants’ ability to manage funds) undertaken on applicants prior to the grant being made? i) If so what vetting procedures are used? 7 What financial accountability monitoring processes are put in place when grants are made? i) Are audits carried out? ii) Why? iii) Who carries out any audits? iv) How are the findings of the audits used? 8 What financial accountability issues (problems) arise in your relationship with recipients? i) What common financial accountability themes have you experienced? ii) Are you able to quantify the scale of the problems eg 10% of grants have problems. iii) Can you give anonymous illustrative examples? 9 What sanctions are invoked if recipients fail to meet financial accountability requirements? D:\219549058.doc accountability requirements further explained to recipient 15