21592 >> Phil Fossett: I'm Phil Fossett, Program Manager, Microsoft... welcome you this afternoon to a great talk from the...

advertisement

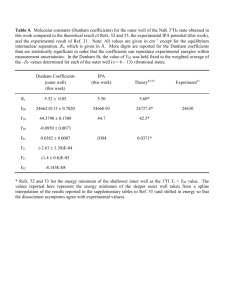

21592 >> Phil Fossett: I'm Phil Fossett, Program Manager, Microsoft Research. I'd like to welcome you this afternoon to a great talk from the Visiting Speakers Series, and I think I kind of live in this space because I do technology transfer all day. I'm really trying to get Microsoft Research ideas adopted inside the company. So this -- and then I think all of us, in all our product groups, that kind of thing, really want our ideas adopted in some way. Well, Peter and Bob are here to discuss some of the frameworks they've developed. We just had a meeting before, and it was pretty exciting just to see kind of how they've identified eight essential behaviors and developed some models. I think you'll find all that interesting. Just for a quick background, Peter is a Distinguished Professor of Computer Science at the Naval Postgraduate School. In his early work, he's focused on operating systems and pioneered in virtual systems. He's one of four principal investigators at cs.net which just received a postal award from the Internet Society. He's basically a self-ordained geek, is what he told me. So he'll give you that background as well. And then Bob's President and Founder of Institute for General Leadership in Boulder, Colorado, not a bad place to be if you like skiing. Providing management, leadership development programs. He's Vice President at Motorola Computer Systems, Action Technologies and also teaches at the Presidio Graduate School. Basically we have an interesting mix of authors coming together between management and technology. And so they put their thoughts together and kind of mixed them up and really have found some truths that I think all of us will find applicable to our day-to-day jobs. With that I'll let them jump into their talk and enjoy. [applause] >> Peter Denning: I have to do a microphone -- am I coming through on the microphone? >>: Yes. >> Peter Denning: Thank you for coming to be with us today. We're going to talk to you about something we've been working on for a long time. I got brought to the subject of technology ideas getting adopted a long time ago. Especially when I was a manager of a research lab and a lot of things weren't getting adopted. Since that's how you get measured as a manager of a research lab, at least in those days that's how we got measured, this was a breakdown for me. I actually started studying management with Bob to try and figure this out. And we eventually discovered that we had some things to teach each other and we wound up writing a book together. So that's what we're going to talk about today. >> Robert Dunham: Yeah. In the 1980s I was studying papers on operating systems in graduate school. Written by this guy. So we kind of started out circling and then we met about 20 years ago and we've been in this conversation that Phil referred to, how does technology and people meet, and the question that's fascinated me is how do people come together and make things happen. And so that's kind of a background thrust of the question we had. >> Peter Denning: Many of the researchers that I've worked with, fellow researchers, somewhere in the back of our minds we always have this question of: Is anybody going to pay attention to what we've come up with, is anybody going to use it for anything? We hope so. Is there anything I can do about that? And that's what we're going to talk to you about today. To help get oriented. >> Robert Dunham: I don't know where to point this thing. >> Peter Denning: There we go. So those of you who haven't already figured it out, we have -- everything we're going to say here comes out of a book we put together. There's the cover. You can't tell a book by the cover. You've got to get the book. It's in the back. And here's kind of a starting point. Couple of statistics for you. The four percent statistic is the success rate of industry innovation initiatives. Whenever we say success rate of innovation initiatives people always ask what's your measure of success? The answer is meeting the financial objectives of the project. So in surveys of business executives, this type of number keeps coming up all the time that they report that four percent of their projects actually meet their financial objectives. Now, that doesn't even mean the project's got anything adopted. It just means they met their financial objectives. Another statistic is this .2 percent here which is a success rate of patents, which this is measured by the amount of patents that get commercialized. Not very high. Want to add anything? >> Robert Dunham: Yeah, that .2 percent, the measure is that the amount of money that was spent to develop what was patented was returned. So this means one out of 500 even meet the costs of creating the idea. >> Peter Denning: Here's another statistic that's a little more relevant to research labs. This one's a little bit more encouraging. It says that 25 percent is -- less than 25 percent is the success rate of research ideas that eventually influence innovation. That comes out of an NRC, National Research Council, report, about 20 years ago. Researchers have taken this both ways. Some say, see, we do better than the industry average to have some influence at some point in time after some number of years. And others say we thought it was much higher than that. We thought that research is the beginning of all innovation. We think it should be 100 percent. And this is what the NRC said. So we're confronted with a desire to create ideas, turn them into action, get them out there, and horrible success rate by several different measures. >> Robert Dunham: So here we are where innovation is a major concern for business. Has been forever. We went to Amazon. We found 9300 titles on innovation. And yet these are the numbers we found. And from the background that we have worked from, this is the indication of a blind spot in the culture. This is when everybody's got a concern, there's a lot of activity around it. There's a lot of books being written. And the results are still pretty bad. One of the historical examples we mentioned in the book is Pasteur discovering germs. Before Pasteur discovered germs, women in child birth had a much higher mortality rate in hospitals than out of hospitals. Even though that's where the healthcare workers, the passionate people for cures, because they didn't have the right distinction. So when we saw all these numbers come together in that data, we said there's a blind spot here. There's something missing in our understanding of the phenomena itself. And so that kind of launched us forward into the investigation. And we had another question that went along with this as we began to explore the domain more, which is that we'll get into more, that the predominant points of view about innovation never answer the question: If I'm innovating, what do I do as an individual human being? Like I've got models. I've got numbers. I've got processes, but what do I physically do? And we found that as part of what guided us to research the blind spot. >> Peter Denning: So what you're about to hear is recorded in one book, not 9300 books. So what if you could raise your success rate with your ideas to be much higher than that industry average four percent? Suppose you could make it 10 percent, 25 percent, 50 percent. Supposing the same thing could happen for your organization or your team. Would this be of interest to you? Yeah. Well, it turns out that there are people we call serial innovators like serial killers, they keep doing it over and over. Killer apps. The serial innovators produce innovations over and over again and they have these kind of success rates, much higher than the average. So we know that such people exist. We're not just talking into the air. We've spent a lot of time examining those people and looking at what makes up their success and we found in an analysis of their success we discovered eight essential practices. And we'll spend a lot of this the rest of this discussion what those practices are and what does it mean to be involved in a practice. The word essential is very important here because it means that there's eight things, eight patterns of behavior, if you want to call them that, to be successful as an innovator you have to engage. If you leave any one of them out, the innovation will fail. That's why we call them essentials. The good thing about it is all the practices are observable, executable and most importantly, learnable. You can see them if you know what to look for you can improve, you can watch how you're doing and how your teammates are doing them and improve. >> Robert Dunham: So the serial innovators, if we look at -- I'll risk mentioning the word Google in this audience, because they have a reputation for generating a lot of innovation. Parts of Microsoft have a history of producing innovations that succeed in the marketplace. John Seely Brown one of our reviewers has been involved in that process forever. And when you look, they're operating in different domains. Now, those are technology examples. We look at Mothers Against Drunk Driving, we looked at family situations. We looked at small businesses and the question we were looking for is there something that's showing up in all these different examples? And that's the pattern we were looking for and we found one. So we're going to explore further what that pattern is. >> Peter Denning: As we start to dig into this, it became clear to us that we needed to make a distinction between invention and innovation. So we discovered that we collectively and the innovators we studied and many would-be innovators, were all very good at generating ideas to solve problems. And researchers specially are paid to do that. They're paid to generate ideas that solve problems. We also discovered that we collectively are pretty poor at getting ideas adopted. So we associate invention with the first thing up here, the creation of ideas. The inventing of the new things. And we associate innovation with the adoption. When something is adopted into practice, people say an innovation has happened. If you actually invented an idea, they will not say that an innovation happened when you invented the idea. They'll say you came up with a great idea. But if you actually press them on when has an innovation happened, there's always adoption there. We find there's a common confusion between these. A lot of people think that innovation, all you need to make it happen is creating good ideas. >> Peter Denning: So as we looked at this and we had begun to unpack a difference between invention and innovation. We found that common confusion; if you simply come up with the new stuff, that helps to explain the one out of 500 patents that pay for themselves because the emphasis was on coming up with the something new not how you get it adopted afterwards. That began to start to explain some of the poor results of investment and return. There was another question that we asked here. We make a distinction between an explanation that is descriptive and an explanation that we call generative. A descriptive interpretation is one in which it says I can see it, I can name it. But it doesn't explain to you how what you're describing got generated. A generative interpretation is this is what has to happen to generate what you're naming. Does that make sense? So what we're looking for is we had a criteria here that helped guide us in looking for these patterns. What's generative? What if we identified is observable, executable, learnable and produces the outcome that we're naming? >> Peter Denning: So when we ask a question what is innovation, the first thing we want to do is acknowledge that a lot of innovation begins with ideas but it's not the whole story. So if you have a story that says innovation is the creation of new ideas, the story usually emphasizes that not every idea counts. The ideas must be new, novel and nonobvious. We want something that surprises people, is the ideal. We want to emphasize creativity. And we love it when the creativity gets expressed as a flash of genius. If we have all of those things, then people will tend to label ideas as innovative ideas. Well, Bob and I say, yeah, we have plenty of that. But yet an awful lot of it is never adopted. And what's missing? We thought that if we're going to start pointing at what's missing, we need to have a definition that specifies adoption as the outcome we're trying to produce and teaches us how to get there. >> Robert Dunham: So we're not saying that there's anything wrong with creativity or new ideas. We're just saying that if that's our only interpretation for innovation, we're missing something. There's a missing piece. And so we're looking what is it we have to add to the creative new idea that makes it valuable that leads to people adopting it. >> Peter Denning: So here's the definition we settled on. Innovation is adoption of new practice in a community. Nice, simple definition. These are some things you have to worry about here in order to understand this definition. First thing is this word Adoption. What it means is to incorporate into the habits, processes, routines, standards, thinking and language of whoever is doing the adoption. So it gets embedded into it. It incorporates into their habits. It's not just something they try out as a procedure or guideline. It's deeply embedded. The second keyword in here is the word Practice. A lot of people really don't understand practices. So we'll be saying a lot about that. But we're making a distinction between mental knowledge and embodied knowledge. Mental knowledge is knowledge that you can describe. I know, for example, scientific knowledge is that way. We can describe the body of knowledge of astronomy, for example, or we can describe the body of knowledge of computer science. So I call that descriptive knowledge. On the other hand, being able to perform these things to the satisfaction of other people is a different story. Just because they have mental knowledge doesn't mean I could do it. A long time ago, when I was director of a research lab at NASA, at that time I was still doing research work on operating systems. I had reputation on operating systems. One day I came into work I couldn't log in because the system had crashed. So I chewed out my system administrator when he came in later. I said if you give me the root password I could log in and reboot the system. And he said with all due respect, sir, we don't trust you to go into the system and configure anything because you'll screw it up. You're a theoretician. We acknowledge you as an expert on operating system theory but we won't let you touch our operating system. If you don't like me for saying that you should fire me. I said thank you very much, but he was aware of the distinction we're trying to get at. I did not have a practice of being able to work and configure operating systems that he would trust to lead to a safe, secure system. I knew about the theory better than he knew about the theory but I didn't know the practice, and he didn't want me messing around with the system given the practice that he was able to observe that I had. So that's the kind of distinction we're driving at here. The ability to perform skillfully to the satisfaction of other people without thinking about it. The final part here, which is important, is community. And that's simply the group of people that you're trying to get to be the adopters. A lot of innovators make the other distinctions but don't have a clear conception of their community and don't know how to pitch what they're doing to the community they're dealing with, and their innovation fails because of that. >> Robert Dunham: There's two points I want to emphasize here. One is when you look at this, this statement applies to any successful innovation. People have adopted it. They're in a new practice, and it's shared in some group. It's also on the way to being generative. A community is something we can see. Right? A practice is something we can see and do and learn, right? Adoption is an act that you can see. And if we can now build the interpretation of how as an innovator we make these things happen, we will have that generative interpretation we're looking for. I also want to point out that if you look at this and think about invention, the skills and practices for being a good inventor don't make you a good innovator to this definition. It's a different set of conversations. That's part of the breakdown when we confuse invention for innovation. We're missing, we're blind to a whole set of skills, conversations and practices that we discovered were needed and that are demonstrated by successful innovators. >> Peter Denning: As we dug into this and started trying to interpret successful innovations using that definition, we found three types of misconceptions. One of which we just mentioned. We called them myths to kind of call attention to them a little bit more than simply saying misconception. But what they are, the invention myth is a belief that all innovations are sourced by inventions. And we found numerous examples of innovations that didn't seem to start with any invention. They somehow were a practice that arose spontaneously. A lot of this becomes visible in the Internet where we can actually see a lot of things happening. The process myth is a belief that innovation is a step-by-step process that we can follow and hire good managers to manager the thing, and if we follow it faithfully, we will get the outcome called innovation. There's numerous examples of that. For example, we mentioned all those books out there. Many of them are concerned with process. They tell you how to run your organization. A lot of people try and run their organizations that way and they still don't get the amount of innovation they want. So the belief that process produces innovation we believe is a misconception. And finally the third misconception is that we call it learnability myth. Maybe we should be better calling it the nonlearnability myth because it's a belief that innovation is, the skill of innovation, when you see it, is fundamentally a God-given talent that some people have and most of us don't have. So if your genes were right, maybe you got the right gene and you're the person who can create innovations and get people to adopt them. The rest of us are stuck with what we've got. We think that's a misconception, too, because we have identified the practice. We have worked with our students and they have learned them and they have produced better results in their own domains. >> Robert Dunham: So we're not saying that invention or process are not an important part of certain variations of innovation. We're saying if you think that's the only framework to think about it in, again, we have our blind spot. So if we go back to some like Kunes, the structure of scientific revolution, when you compare it to the outcome, the results aren't there, you have to test the boundaries of your thinking. So we're looking for an answer that doesn't get contained or limited inside these explanations. >> Peter Denning: In the process of analyzing the literature, we found a number of models that have become popular for trying to explain how innovation works. Just going to mention them here for you and then we'll go on and actually look at the eight practices we've been talking about. The mystical model you might be thinking about is the lowest order model. It's simply that innovation is a talent that some people have. It's a gene that some people were born with. The rest of us don't have it. And beyond that we really don't understand where it came from or anything else. So it's kind of a mystical thing that some people have. The process models are the ones that try and say innovation is a process that you can organize in your organization and manage carefully. The leadership models say innovation is really the function of leadership and therefore you need the right kind of leaders to lead the projects and do the work and you'll then get innovation. And finally the generative one, which is the one that we have been studying the most and promoting means that you actually have the practices that generate the innovation. >> Robert Dunham: In this last one, if we can come up with an interpretation of something that a human being can physically see, do and produces a result, we've got kind of a range of capabilities for that. One is that it's packed into one body. And there's a few serial innovators that seem to have it all packed in one body but there's a range of skills, a range of things that have to happen. In the human interactions with the adopting community. So if you can't get it all in one package or one person as the innovator you can build a team, but the same skills have to be available to that team that are demonstrated by the master innovator. >> Peter Denning: This diagram shows one of the most common models for trying to understand innovation. And we call it the pipeline model. It was first put into print for the scientific community in 1945 by van DA Var bush. Some of you may have read his paper, Science, the Endless Frontier. It's easily available on the Web. But he talks about the way science works. And therefore that's the way government should try and help science. Everything begins with researchers and inventors who somehow receive inspirations from things around them. They produce scientific papers and prototypes. Some of these get taken up as R&D projects which produce commercial prototypes which then go into production, which produces inventory and then the marketing department takes it out and sells it as products in the marketplace. So this model says that's the innovation process and in this model it becomes very obvious that researchers are really key to the process. If you don't have them, there's nobody generating the ideas to feed the pipeline. You won't have innovation. >> Robert Dunham: Early in my career I was a software developer, and then got into software development management and became a VP in Motorola computer systems. And over that span of my career I developed software development models for my organizations or a company level product development model five different times. And sometimes it seemed to work and sometimes it didn't. And that was my earlier experience of beginning to say having the process definition wasn't enough. And so I was primed from those early experiences what's the missing ingredient. >> Peter Denning: Somewhere in the -- must have been the early '90s, a flood of discontent going on in Washington in the funding agencies who fund in university research saying we poured all this money into the universities and we haven't got what we were hoping for. We haven't got better healthcare, better economics and better defense as a result of it. And there was a lot of talk about cutting back on the amount of research that the federal government would support. Well, somebody came up with the idea that no, no, you shouldn't do that because the pipeline model that you're criticizing is actually not the complete picture. The pipeline model tends to distinguish between basic research and applied research. The basic research is what those researchers are doing on the left end of the pipeline and the applied stuff is going on in the R&D department and maybe in some of the marketing. So you've got two things. Basic research and applied research and according to van DA Var bush you want to separate those. And in -- when was it? Around 1990 a guy named Donald Stokes said we're missing out on a third style of research. And he actually named three styles of research according to the exemplars that we like to hold up. So Edison was a researcher who was very experimentally oriented researcher, really interested in getting things to be applied. Spoor was a physicist, Neil Spoor was a famous physicist who said he didn't care whether anybody used his ideas. He was simply following ideas to see where they would lead. And Stokes said you're forgetting about the third guy here Pasteur who did both of those things. He was interested in the basic science and he was also interested in getting it adopted. So he said what's missing in our picture is this Pasteur idea. And he pleaded for everybody to recognize the Pasteurs and develop the Pasteurs in our midst. And if you put that into the model, he said the model would then work. Well, as you might suspect, it didn't still the conversation in Washington. They still criticized research. >> Robert Dunham: So we've got the new quadrant here. We've identified the Pasteur version of innovation. The question still remains how do you do that? What specifically does a person do. >> Peter Denning: What did Pasteur do? >> Robert Dunham: Yeah, well, he did the anthrax solution. So I'm not going to go try to do that again. But it still begs the question how do we get down to this level of observerable behaviors of human beings. The models are too abstract. >> Peter Denning: There's another model which I will not even attempt to describe to you, I'll just name it. By famous guy named Everett Rogers who proposed it in 1962, it's called a diffusion model, and he said, yeah, somewhere in the background there's a pipeline, but the thing that's really important in this pipeline, he pulls out and breaks it up into these five big arrows here, where he's focusing on what he calls the communication process from the inventor to the community. So somehow or other the idea of the invention is being communicated and people in the community are deciding whether or not to adopt it. And to get the innovation, you need to worry about how you communicate, how you influence them and how they make their decisions. >> Robert Dunham: So this is getting closer, if you look at the bottom line, we're describing some activities and actions that a person takes, persuasion, decision, implementations a little more abstract. Knowledge, I don't have a foggy idea what the action is. But this was the closest we got to describing a set of executable actions by a human being but it was still at a level of abstract -- what's persuasion? How do you do that? Until we know how to do that, we're still not at a generative level to generate the innovation. We're still describing it. >> Peter Denning: So we're not going to try and explain this, this is in the book. But we actually got the picture out of Roger's book so it's his picture. >> Robert Dunham: When you have a slow evening you can spend it with that diagram. >> Peter Denning: This is another important idea that Rogers introduced into the discussion which we think is very important. We called it the adoption distribution. He said that the audience, your community, who you want to do the adoption actually is decomposable -- not completely decomposable, but into components, which he called the innovators, the early adopters, the early majority, the late majority, and the laggards, and each one of these people had a different degree of receptivity to the new idea. So the innovator type of person is a person who is always looking for a new idea. You tell them something and he's on it right away. Even before you finish your sentence, he's ready to try it out. That's the nerd, I guess, right? The early adopter is more like a visionary who sees the benefit of something and comes in early. Says I'm going to be one of the first ones to try out the new technology. The majority people are people who are more cautious. They want to make sure it's properly supported before they're going to come in. And finally the laggards are the people who you can't convince at all. Some of them never come in. You just have to wait for them to retire or expire. Okay. The important contribution here, which he got from his data was that people have different degrees of receptivity to adopting, and if you're going to be successful you have to take this into account. >> Robert Dunham: Yeah, there was -- Rogers did this work and then Jaffrey Moore wrote a book called Crossing the Chasm. He said people who looked like they were on a successful track by selling to the innovators, and maybe the early adopters, had companies that crashed and burned, because they didn't understand that when you got to the majority, you had to have a different set of interactions, a different set of conversations. And so each one of these again is how do you interact with the customer set or the adopting community. And it varies for each one of these categories. >> Peter Denning: Let's talk about the eight practices and we'll spend the rest of our time between now and 3:00 on this topic. So everything we just said is part of the background that we picked up as we went through this trying to understand who had done what before, what people had discerned before and where we thought the blindness was. When we went through our research and discovered these eight practices, we made a diagram out of them. So you can see them there. There's the names of them. Sensing and visioning. Offering, adopting, sustaining. Executing, leading and embodying. Each of these is colored in a different way, because there's a few things you can, that will become obvious to you as we talk about it. But, first of all, even though we've got numbers on them, the numbers simply one level simply distinguish them so there's the first practice, the second, the third, we actually need all eight of them. The second thing is that there's actually a sort of a temporal sequence among the five on the outside of that wheel. So if you look back over an innovation that's happened, you'll see that sensing, which has to do with sensing the new possibility that you can work on, sensing an opportunity, that has to start the process. Envisioning is about telling a story that engages your audience in the new possibility. That has to come after you think you see what the new possibility is. Third thing is offering, which means that you offer to work with your community to make that new possibility happen. And obviously it seems like you better have the possibility in hand to offer it. Adopting refers to getting people in the community to try it out, to do it, to adopt it, for the first time. Many people are willing to try something out but they're not willing at that point to make a commitment to stay with it, but they're certainly willing to give it a shot. So a lot of us spend a lot of time just trying to win that first adoption. The fifth practice is sustaining is after you've got people to adopt for the first time you want to get them to stay with it. It's not quite the same issue anymore. So those things kind of go in a series there. You can think of it that way. If you study it more you'll find that the innovators actually jump around. They think they have a possibility. They'll tell a story. Nobody will resonate. They'll go back and rearticulate the possibility, try another story. Finally they've got a story that works. Then they'll offer it, a lot of people won't accept their offer. They'll go back and retry their story and get a better story. Try that one. Now people are accepting their offer. And then they try to get adoption. They don't get that. They go back, reformulate the offer. So they're going around trying out new things experimentally all the time. And so if you actually study it up close, you'll see that although there's a kind of general sequentiality in those five things that they're not strictly sequential at all. You want to amplify on that? >> Robert Dunham: Yeah, what we found when we tested this against the examples of successful innovations and failed innovations, we found that these milestones in the process have to happen. If any one of them doesn't happen, you're not going to have an innovation. If no one hears an offer, no one will respond. If no one adopts to try out the innovation, it's not going to happen. If no one commits to sustain it, it won't happen. So at that level, these are like anatomical milestones along the way that have to happen and it brings us back to our generative question. Now that we're naming X of making an offer of producing an act of adoption of engaging in the activity called sustaining how can we unpack that so you can actually see it and do it. This is where we landed from our research. This now begins to show -- for example, if we go to research, research might be thought of happening before sensing or is part of the sensing activity. You want to go to innovation, you gotta have these other steps. And you have innovations that have succeeded here at Microsoft. From our testing of this, every successful innovation had these things happen and every failed innovation got blocked at one of these points. And usually they're blocked because the innovator gives up because they've been blocked. The successful innovators see blocks as part of the process, not a stopping of the process. So for every one of these practices we list the common breakdowns which innovators need to be able to overcome. >> Peter Denning: The process of studying this we also found three more practices that we tended to call environmental practices. Because they're not sequential. They're part of the support for the other five. So executing means the ability to articulate the commitments, the plan for carrying them out, and then manage the whole set of conversations that get the commitments fulfilled filled. Some people call that project management. Some people call it project execution. But something like that has to be in there or none of the rest of it will actually happen. Leading is almost redundant in many ways, because if somebody isn't being proactive and taking the lead to make each of these other things happen, they won't happen. But there's a particular style of leadership that we found seems to be most appropriate and most effective in dealing with, in making innovation happen. And finally number eight, we call embodying. And this is the business of as an innovator, learning to embody the skills and practices you need to do those things, or if your company, an organization making sure that you have configured your team or your organization so that as a group they can do these things. But it also means understanding how your community is going to embody the practice that you're proposing that they take up. And how do you teach them that, how do you convince them to do that? So this is a rich practice that has two sides. It has a side that's pointing at yourself, but what do you need to learn, but it's also pointing to your communities, what are they trying to learn. >> Robert Dunham: I just want to emphasize on the embodying part. This is the place we found when I said we tend to be too abstract in interpretations of human action. We have to get down to actually describe what bodies are doing and how you influence them. What is learning? How do you change habits? What happens when two people interact, they connect or don't connect, what do you do with that? These are skills that were natural for the natural innovator, but what we have done is try to say what is it that they're doing, how do we articulate them as observable executable skills that through practice you can develop? It turns out that those central three are a set of skills that also apply to leadership. And I've actually been working with those for 30 years. And they were one way that we were able to -- and Peter as well-map these fundamental skills that are observable and executable and say, yeah, the innovators are doing that. >> Peter Denning: Well, now that we've given you the overview, first two practices number one and two we call the practices of invention. Because that's where the ideas get created. The next three offering adopting, sustaining we call the practices of adoption. That's where the commitments are made that produce adoption. And finally the three in the middle we call the environment, because they create an environment in which the other five practices will be successful. So we've actually said some of this. We're now going to lead you through the eight practices and you can -- we'll do it in a way where you can make a self-assessment of yourself and see how you're doing while you're here, take something away with you. And also while you're at it, take a look at how your organization, Microsoft, is doing in regard to these practices of getting things adopted that you think Microsoft should be getting adopted. So each of these practices features a conversation that produces an essential outcome for innovation. That's one of the reasons these things are learnable is because if you understand that it's getting into the right conversation, then you know how to make it happen. The second thing is that one of the things we're really interested in is what commitments did the innovator make at various points, and that becomes the point of those conversations, produce those key commitments. Each of these conversations has an anatomy by which we mean a structure that if you follow it and you complete all the pieces of the structure you'll get the outcome. Each of these practices also has characteristic breakdowns, which are obstacles that we call them breakdowns, but they're obstacles that prevent you from completing the practice. And it turns out that there's, with each practice, there's signature ones that keep popping up all the time. And so part of the job of the innovator is not only to carry out the structure but also to deal with all these curve balls that keep coming up but they're very predictable in what kinds they're going to be. And so we believe that the skill of each practice is simultaneously a skill of following the anatomy and also coping with the breakdowns. Breakdowns are actually a natural part of the process. It's easy for us to curse at them when they happen, but that's not how you get judged. You get judged when you go past the breakdowns and produce the result. If any of these conversations fails, the innovation fails. So they all must be there. >> Robert Dunham: I just want to comment here, the word "commitment" has several meanings if you go to the dictionary. The way we're using it it's a moment where the human being moves to intentional action and sometimes it's not what they say. Sometimes they'll say one thing and do another. But we are looking for those moments of yes we're going to move into action, both the innovator and the adopting community, those are moments that are observable and listenable. And they're a fundamental skill for leadership as well as innovation. And leadership and innovation overlap. You can't really do one without the other. >> Peter Denning: Now, you've probably begun to see this, and we've mentioned it already, that it may be a tall order to ask an individual to learn all eight of those things. Like I started out myself as a geek. So I specialities in practices one and two. Then as a research manager, I had to start to learn practices three, four and five and plus some of the other ones. And over a period of time I learned that I didn't know anything about those things, really. And it took me many years to learn them. You may be in a position where you say I don't have many years to learn something. I've got to get something to happen sooner than that, what do you do? Well, you find other people that already do those practices well and bring them on to your team. So these things can be a guidance to you in how you form a team so that your team as a whole has everything that it needs there to accomplish the innovation that you're trying to do. It also works, you generalize this to networks, in recent years have been a lot of interest in social networks. There's been a lot of interest in open software networks and the kinds of innovations that seem to arise in those settings. We've looked at those and analyzed them and we see that the successful ones have been like incubators where the eight practices arose spontaneously in the network because they were almost the only thing that would help the network succeed. So it works in networks. It also works in organizations for the same reason I just said, that the organization can put together people of different talents and skills and if they coordinate them well, they can realize teams and projects that have the eight practices and get things to be adopted. So all of that is spelled out in detail in the book but I'm just telling you that even though we formulate this as something that you can learn personally, you can also generalize it to your teams, your networks and your organization. >> Robert Dunham: I want to do a timing check here. We advertise the presentation. And then there's a workshop. We're going to go until 3:00. We're actually going to go through and detail each one of the practice of the process, assessment of yourself and your organization begin to see what's present and what's missing. We invite you to stay for that. If any of you have to leave this would be the transition point and I want to open up for some questions. What did we provoke for you, what questions do you have, how can we help you integrate what we're talking about here? >>: I'm wondering if you're familiar with the work in knowing doing gap, have you come across that? >> Robert Dunham: I've heard the phrase. >>: It's a group of professor down in [inaudible] it's very similar observation to your generative approach. >> Robert Dunham: Yeah. So I'm not sure I have a precise understanding of what they're talking about, but I can go back to an ancient distinction in our culture knowing is used in two different meanings. One is knowing about, which means you can describe it. And the other is know how, which means you can do it. So we're basically saying that our culture has been dominated by the culture of knowing about, of being scholars, of being able to describe and analyze and talk about, but we're saying, no, for innovation we have to get to what we're calling the generative, the know how, and bring that back and having the knowing about is not enough to produce the result. Jeffrey. >>: The eight practices embodying, it seems to imply that this is community needs to make change, has to transform. That seems to be the focus. But it would be correct in also saying that it's the innovator as well that needs to be willing to also be transformed by it? >> Robert Dunham: Absolutely, yeah. I'll give my comment here. The process that we've laid out here is not one where you're imposing or I know the answer. It's we have a fundamental principle of human interaction. It's called blending. And blending means you know how to connect with that human being in their world, in their concerns, in their situation, where they're at, which means you have to be very flexible and be able to bring the value of the innovation to that situation. It's not about imposing. >>: So there's an element of courage? >> Robert Dunham: Absolutely. Risk -- one of the things that we talk about as the innovator is the aspect of the sense of destiny, that the breakdowns are not the end of the process. >>: The one I wrote down. >> Robert Dunham: Peter? Keith? >>: I have not read the book yet, and I've noticed you did have a couple of references to Blain Christensen in the new book. And one of the things that leaps out at me as I just get this initial cursory understanding of the work that's been done is, do you make a distinction between technology innovation and business model innovation? The reason I bring Christensen in that discussion is because much of what he talks about in his description of the innovator's dilemma is that in order for disruptive innovation to happen, the invention, the innovation has to happen, one. Two, in most cases there's a new, what he calls a new value network that emerges that supplants the old value network that enables that disruptive to be truly innovated. And the question -- and also cited Google earlier and Amazon in the book, in which case every case there's new value networks emerging in addition to the technology innovation that occurs. And so what I'm trying to get at is the question is, do you see those as intrinsically different types of innovation or do you see them as essentially difference in, not a difference in kind, but just a difference in [inaudible]. >> Peter Denning: I just say they have different target domains, technology innovation is trying to build some sort of technology tool and people presumably would try and use that tool and do something better with it by having the tool. Business innovation tends to be either an improved business process, different way the business goes about doing something, or maybe a completely different business model, which is a different conceptual framework, to carry out the business in. So there may or may not be technologies as part of that. Okay? But the eight practices are still there. If you want to produce a new technology tool to help people do something, you've got to do those eight things. If you're going to get them to adopt it. If you want to change your business or your business model, you've got to do those things among yourselves to make that new business model happen. >> Robert Dunham: So let me add to that. So at the level of the eight practices, right, it's about seeing the possibility that people care about that produces the assessment of value that they're willing to commit themselves to and give up old practices. That applies to anything. The content can be totally different in different domains. Healthcare. Technology. Right? Finance. The content -- but those aspects of the conversation are part of the conversation itself and they apply to every domain. >>: So you guys were saying that failure happens when innovators see blocks and stop. Are you going to talk at all about what the triggers are? Because sometimes you have a bad idea, right and sometimes there's a block for a reason like you shouldn't move forward. Like sometimes you need to end that process. Do you talk about that at all? >> Peter Denning: Let me just comment on that. A bad idea is not intrinsically about the idea it's about the assessments that other people are making. So if you come up with an idea and they say that's a bad idea, what they're doing is making an assessment and telling you that I'm not going to adopt it because it's of no value to me. There's numerous examples where the same idea came up in a different context and they considered it valuable and they adopted it. So you can't focus on the idea itself. You have to focus on the community and what kind of assessments they're making in reaction to you presenting them with an idea. So I think we try and do that. >> Robert Dunham: And when they make that assessment, the key assessment they're making is one we call of value. If you begin to see there's no community that values your innovation, they neither give it up nor begin to modify the innovation. So that's where the innovator is learning through the process. Not just being stopped because I'm only going to sell what I got. No, it's about maturing the innovation through that feedback. >>: So one of the things we talked about is how a truly innovative idea tends to change the power structures within a community. So what suggestions do you have or maybe you could cover it in the workshop, that might allow you to get through that block? >> Peter Denning: Well, let me just back up. When we analyze these two, one of the big phenomena that the innovator has to deal with is what we call resistance. Resistance means that there's some members of the target community who don't want the innovation. And the most common reason, not the only reason, but the most common reason that they'll never talk about is that they're the ones that lose power if this new thing comes into practice. And, of course, the people who gain power, they're going to be in favor of it, but the people who lose power may be resisters, and if they are powerful enough they can stop the whole process. So if you're going to be successful at innovation, you have to stop and think about where the resistance is going to come from and what you're going to do to deal with it. How you're going to seduce the resisters into coming along with you or can you isolate them so that they can't do any more damage. But if you just leave it alone they will resist and you'll fail. And that happened -- oftentimes not all the resistance comes up in your first adoption because people say well it's just an experiment or something. But if they see you're serious about sustaining it, there may be more resistance. So in both these cases you encounter resistance. It may be a different flavor, but it's a very integral part of the process. >> Robert Dunham: That's part of how do you portray the innovations being valuable to as many players as possible. And the ultimate outcome is often beyond the point of resistance. So there was a book written in the '90s by Praglett and Hammel [phonetic] called Competing for the Future. Page 24, they say here are the list of companies that were number one in the world in their industries that no longer exist, because they were not willing to innovate. They resisted the innovations or didn't create an environment for it. So if you can go to the end result for the entire gain, that's where you get your power from as an innovator. >> Peter Denning: One of the things we found is that I hate to call it a technique, but a practice that's been valuable to deal with some resistance is a blending practice. And what I mean there is that the offer you make, the idea you're asking them to adopt blends in with what they already do. They see it as blending in and improving upon it and valuing and adding value. So they won't resist. Even though in the back of your mind you know that if they adopt it, that eventually it's going to be disruptive for them. But that's not the story you're telling. The story, the offer you're making is not on the eventual disruption. It's on the value they get by adopting it now. An example of that that we cited in the book is Apple iTunes. It was originally presented as a way of sharing music without violating copyrights. Violation of copyrights was big on people's minds because of the Napster case. And in the back of their mind they knew that eventually it could be disruptive because they didn't, a guy writing music could publish directly through iTunes and not go through a music publisher. Now the publishers are complaining about iTunes because it's disrupting them but Apple doesn't mind that. That's an example where they blended with what the concern was at the time and did not push on the idea that it might be disruptive. If they had pushed on that idea from the start, it probably would have died. So there's an art to blending with the concerns that are already there and having that blend overcome some of the resistance that might exist. >> Robert Dunham: Let's take one more then we need to move to the workshop because we've only got half an hour left. Go ahead. >>: How sequential is this iterative process in the sense that let's say you're starting a project and you can hire a bunch of people and can you start people already working on the adoption and sustain the potential blocks while you're still working on kind of maybe offering step or you really have to iterate it so much that generally [inaudible] essentially reach them? >> Peter Denning: I would say that an aware innovator who understands all this is going to be looking ahead to future steps. Maybe he's not doing much about them now but as he's thinking about the offer and telling the story, he's going to be thinking what kind of resistance might get stirred up to what I'm proposing? Can I diffuse that resistance? Can I modify my story so it doesn't stir up resistance? Or maybe I'm going to make my offer and people are going to start asking about the eventual infrastructure that supports it, and if I don't have anything that sounds like an answer there, they're going to turn me down. So part of my offer might be enough of a story about how I'm going to sustain this thing that they're going to be interested in the offer. So you have to take the big picture view that as the innovator you know, you see the whole picture and you're trying to refine that whole picture but you don't know all the answers at the beginning. >>: Is that actually necessary to envisioning this entire pipeline is essential aspect of part of this envisioning step? >> Robert Dunham: So the example that comes up for me is writing code. You can be working on your test technologies and your acceptance technologies before we even know the products even specify. So there are pieces of the downstream that you can go to work on productively early. And once you do the design and if you're going iteratively and getting feedback, of course you're modifying all the time and everything's flexible. Is that ->>: My follow-up question is this actually essential? Like Peter's answer made it sound like it was essential, that you have to address the statement for your potential customers before they even think about adoption? >> Robert Dunham: Yeah, what we're saying is sustaining is an event that will happen whether you think about it or not. People are either going to commit to integrate it into their practices or they won't. And if you see that's for that particular innovation you're pushing, that that's going to be a big issue for your clientele or your adopting community, you probably want to be ready for that. Does that make sense? >>: This is a question about being a necessary step, but do you have like when -- do you have to envision -- you could and your answer was it could help the adoption strategy, but I'm asking ->> Robert Dunham: I'm saying it's unavoidable. It's nondiscretionary. It will happen. >>: What I'm asking about the earlier phase, when you're envisioning the innovation, should you or do you need to also think about the later steps, the answer was sometimes you should. But my question is, is it necessary? I guess the follow-up, is it necessary? >> Robert Dunham: I think it's variable. I think if you're going from an envisioning to an offer let's get started and everything's emerging, that I could see that happening. But I would say that doing some advanced thinking about who is the clientele is and what the issues are going to have at the steps will probably be productive. Okay. Let's move to the...