Motivational Interviewing Jen Carlson & Katie Miller March 14, 2016

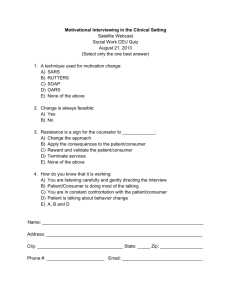

advertisement

It’s fun, freeing, and fruitful! Motivational Interviewing Jen Carlson & Katie Miller March 14, 2016 Overview: • Example of non-motivational interviewing • Assess current comfort level and areas of interest • MI basics • Assumptions about motivation • What, when and how • Rolling with Resistance pointers • Practice skills with a partner First, let’s visit a patient room near you: • Hint: This is not motivational interviewing Thoughts? • Have you been here? • From a doctor perspective, how did this go? • From the patient perspective, how did this go? Motivational Interviewing to the Rescue! • What does it mean? • What’s your comfort level? • Where do you need help? MI Basics • What • When • How Assumptions About Motivation • Motivation is malleable • Subject to change in context of patient-provider relationship • The ways in which one talks with patients can influence personal motivation for behavior change What is MI? • A collaborative method of communication • Designed to strengthen motivation for and movement toward a specific behavior change • Key is to elicit and explore the person’s own arguments for change Where did it come from? • Grew out of the “Stages of Change” model of behavior change • Rollnick and Miller developed initially for work in substance abuse treatment (1980s) Stages of Change/Provider tasks Patient Stage Provider tasks Contemplation (getting ready) Explore ambivalence about change Identify reasons for change/risks of not changing Increase confidence in ability to change Preparation (ready) Goal setting: help patient develop a realistic plan for making change Maintenance (sticking to it) Help identify and use strategies to prevent relapse Relapse (learning) Help patient renew the processes of contemplation and action without becoming stuck/demoralized Precontemplation (not ready) Increase patient’s perception of the risks and problems with current behavior. Assist with harm reduction strategies. When to use MI • When you are working with a patient on behavior change • What kind of behaviors? • medication adherence, smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity, diabetes control, sexual risk taking, substance abuse problems, problem internet use, completion of recommended screening or diagnostic tests or specialist/psychologist referrals, stress management You find yourself banging your head on your desk You want to have an enjoyable patient interaction You don’t want to be the cause of a patient’s resistance You will not use MI style of communication all the time: Styles of Communication: Directing Following Guiding All are valid and useful to mix and match: guiding is most effective for building motivation and eliciting behavior change Attitude is Everything Style/Spirit of MI: • Collaboration (partnership between patient and doctor with doctor acknowledging the patient’s expertise about themselves) • Evocation (doctor evokes the patient’s own motivation and reasons for change) • Honoring patient autonomy (though doctor can provide information/advice, acknowledges that change “is up to you”) • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=80XyNE89eCs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URiKA7CKtfc 6 Guiding Principles: • Resist the righting reflex—tendency to tell people the right way to do things • Understand the patient’s own motivations • Listen with empathy and express empathy 6 Guiding Principles: • Empower the patient and support self-efficacy • Develop discrepancy: help point-out differences between a patient’s current behavior and future goals or values • Roll with resistance: avoid argument, simple acknowledgement of a patient’s disagreement/emotion/perspective, verify your understanding matches the patient’s perspective, shift the patient’s attention away from the stumbling block, assure the patient that they are in charge of the decision to change How: Some practical tips • You may use 1 or 2 of these techniques during a visit • In a typical clinic visit you will likely not have time to use all of these techniques How: • Ask permission to discuss the topic further. • Ex: “Would it be okay if we spend a few minutes talking more about ______?” • Help the patient hone in on a specific behavior • Ex: If the patient wants to lose weight, do they want to focus today’s discussion on eating or physical activity? How: • Ask open-ended questions to explore patient perspective • Ex. Tell me about your exercise habits? What concerns you about your eating habits? What are the pros and cons to changing and staying the same? What is a typical day like for you and where does exercise fit in? Good things/Not-sogood things about target behavior? How: • Use reflective listening—listen carefully and then rephrase or replay the key points of a patient’s statements. • Ex. -You are getting frustrated by your mom telling you to exercise. • -So on the plus side TV helps you unwind and spend time with your friends, the downside is you are sedentary for hours and are getting to bed too late. How • Use summarizing—ensures mutual understanding, can point out discrepancies between the person’s current situation and future goals, can move conversation toward discussion about change • Ex. You enjoy watching TV after work since it helps you unwind and you can spend time with your partner, but you are beginning to worry that you are not getting enough exercise, and you are getting sucked in so you are getting to bed too late. How • Make affirmations: can take the form of pointing out personal strengths/efforts or statements of appreciation and understanding of struggles/skills/goals/values • Ex. -I know that you worked very hard and were able to quit smoking in the past, which makes me think you will be able to tackle this challenge. • Ex. -I appreciate that this is an emotional topic for you to discuss, thanks for helping me understand the issue more fully. How • Listen for “change talk”: ex “I’m not ready to change” “I want to change” “I should change” “I will make changes” How • Assess commitment to change/Set goals if appropriate • Try using an “importance ruler”: • Ex. On a scale from 1-10, with 1 being “not important at all” and 10 being “extremely important” where would you put getting more sleep? Why are you a __ instead of a _____(lower number)? How • Try using a “confidence ruler”: • Ex. On a scale from 1-10 with 1 being “no confidence” and 10 being “extremely confident,” how confident are you that you can increase your exercise? Why are you a ___ instead of a ____ (lower number)? • Assess stage of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, etc.) and stick to appropriate provider tasks How • If patient is ready to make steps toward change, decide on a “change plan” together. • Ex. Where do you want to go from here? What changes are you thinking of making? • Explore challenges • Write down action plan and summarize Skills for Rolling with Resistance Shifting focus • Temporarily shift attention away from contentious area to one of common ground Emphasizing personal choice and control • Assure that any decision about whether or not to change is the patient’s choice; only he/she can take action towards change Reframing • Restates what was said and invites patient to consider this viewpoint. Agreement with a twist • Combines a reflection and a reframe • Requires a light touch and sensitivity so that it does not sound like sarcasm or criticism Coming alongside • A last resort: agreeing with expressions of negativity. • Extreme exaggeration intended to bring patient back to a more open posture. Pick a partner Case 1: • Philip is an 18-year-old high school senior who comes to your office for a regular health supervision visit. His dad stopped you in the hall prior to the visit to say that he wants you to “make Philip stop smoking.” The psychosocial history reveals that Philip smokes about a pack of cigarettes a day and has no interest in cutting back or quitting. In fact, he volunteers, “I love to smoke.” Philip is planning to work as a car mechanic after graduation from high school. He plays no sports. His physical examination is completely normal. • How do you start using MI? Case 2: • Janie is a 16-year-old junior in high school who comes in for follow-up of a new prescription for contraception. She is sexually active with one male partner and had started an oral contraceptive 4 months before. Janie states that she stopped taking the pill a month ago because she was having a lot of vaginal spotting. When you ask how taking the pill at the same time each day worked for her, she sighs, “I just couldn’t seem to remember to take it, no matter what I tried. Maybe I’ll just stick with condoms for now. Maybe I will be able to remember to take the pill more regularly when I get back to school in the fall.” You thank Janie for being honest about her difficulties in taking the pill. • What do you do next?