Promoting and assessing value creation in communities and

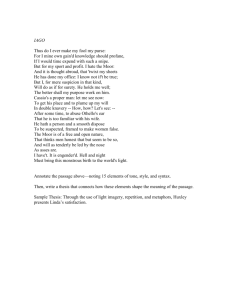

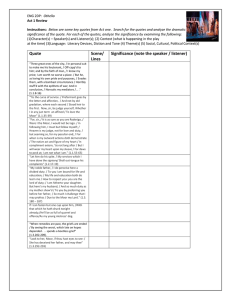

advertisement