midterm will be returned at end of lecture

Econ 522 – Lecture 14 (March 10 2009)

midterm will be returned at end of lecture

section at lecture time Thursday this week; no section meetings Friday

HW2 (contract law) due March 31

(written on board before we start)

Expectation damages include anticipated benefit from reliance

efficient breach and investment in performance

overreliance

Expectation damages exclude anticipated benefit from reliance

inefficient breach and investment in performance

efficient reliance

Last Thursday, we worked through examples of breach, reliance, and investment in performance. We found that

When expectation damages include the anticipated benefit from reliance, we get o efficient breach, and efficient investment in performance

why? seller internalizes the full cost of breach, and makes efficient decision o inefficiently high reliance

why? buyer reliance imposes a negative externality on seller – since he has to pay more if he breaches – so buyer does not bear full “cost” of reliance

On the other hand, when expectation damages exclude the anticipated benefit from reliance, o inefficient breach/investment in performance

breach imposes a negative externality on buyer, so seller does not bear full cost o efficient reliance

buyer bears full cost, full benefit of reliance, makes efficient decision

This is what Cooter and Ulen call the paradox of compensation o neither rule gets both parties to act efficiently

- 1 -

We already saw one proposed solution to this problem

Modify expectation damages to include the benefit of reliance, but only up to the efficient level of reliance, not beyond

This way, buyer has no incentive to over-rely, since he won’t get that benefit in the event of breach

And seller still bears full cost of breach, so he makes efficient decisions as well

The textbook discusses another clever, if unrealistic solution: anti-insurance

What’s causing the problem?

Well, you only make efficient reliance investment if the damages you receive don’t reward you for reliance

And I only make efficient investment in performance if the damages I pay do include the benefit of reliance

One way to fix this: make the damages you receive different from the damages I pay!

How do we do this?

You and I have this friend, Bob

Bob likes money

So we go to Bob and say, hey Bob, here’s a deal for you

I’m planning to build a plane

He’s planning to buy the plane

He’s probably going to want to build a hangar

I might end up not building the plane

Here’s what we need you to do

In the event that he builds a hangar and I don’t build the plane,

I’m going to give you the value of the plane with the hangar;

And you’re going to give him the value of the plane without the hangar

And you keep the rest for yourself. OK?

And Bob says, “cool!”

- 2 -

This is called “anti-insurance”

Rather than buying insurance from a third party, you and I are basically entering into this additional contract where if things go bad, I owe Bob some additional money, beyond what I pay you

By doing this, we set both our incentives correctly o You only get the benefit of reliance if I perform, so you invest the efficient amount in reliance o I face the full cost of breach, so I invest the efficient amount in performance.

Now obviously, Bob is happy to do this for free

But now we go to our other friend Carol, and say, Hey, Carol

Here’s a deal we’re offering

Give us $5 now, and if he builds a hangar and I don’t deliver a plane, you’ll get the difference between the value of the plane with the hangar and without the hangar

And Carol realizes this is worth more than $5, so she says, “sure.”

But now we go back to Bob, and we offer him the deal at $10 instead.

And if we make Bob and Carol compete for this deal, we should be able to get them to pay a fair amount for it up front

If they’re risk averse, of course, they’ll need to be compensated for taking on some risk

But if we have a risk-neutral friend who’s smart enough to understand the probabilities and figure out what each of us will do given our incentives, we can get them to give us the full value of the anti-insurance deal ahead of time, and divide it up among ourselves

So this way, we can give ourselves incentives for efficient reliance and efficient investment in performance at the same time.

So that’s one way to solve the paradox of compensation – even if it’s pretty unrealistic

We already mentioned the idea of limiting damages to include the benefits of efficient reliance but not overreliance

What courts actually do, rather than basing damages on actual or on efficient reliance, is to base damages on foreseeable reliance

- 3 -

That is, they base damages on what the promisor could have reasonably expected the promisee to do, not what he actually did

This was the decision in Hadley

Since the shipper could not reasonably expect the miller to rely so heavily, he was not liable for the lost profits o Most millers at the time had more than one crankshaft o So a broken shaft would not typically lead to shutdown

Under the doctrine of foreseeable reliance, if Hadley had told Baxendale that his mill was closed until repairs were made, then Baxendale would be liable for lost profits due to delay o By informing Baxendale of the reliance, Hadley would have made it foreseeable, and therefore compensable

Next topic: timing

Everything we’ve done so far has assumed that the timing of the contract is fairly rigid

first, we sign a contract

next, you decide how much to rely, and I decide how much to invest in performance

Then, things happen, I decide whether to perform or breach, and if I breach, I pay damages.

But often, the different stages may overlap a bit more

If I’m building a house for you, I’m unlikely to build it in a day

You may be able to see how some of the progress is going before making all of your reliance investments

Similarly, the question of when someone decides to breach a contract may affect the damage done by breach, which may therefore affect damages.

Suppose you’re a farmer, and I’m a grain wholesaler

You agree to deliver me 10 tons of corn on a given date at a given price

This is a futures transaction – a promise to transact a good on a future date

In some cases, there may be a going market rate for corn delivered on that date

And this price can rise or fall as the date approaches.

- 4 -

So we agree that you’ll sell me 10 tons of corn next June, at a price of (I don’t know the price of corn), say, $500 per ton

Over the course of the winter, circumstances may change o maybe it’s a dry winter, so irrigation will be more expensive in the spring o maybe other crop prices go up and you decide to plant wheat in more of your field.

If you decide to breach, you could wait until the last minute to tell me o in which case, damages might reflect the cost to me of buying corn on the spot market, that is, the day I was expecting delivery.

Alternatively, you could tell me in January that you plan to breach our contract o This would allow me to contract in advance with someone else to sell me corn in June o which might be cheaper than if I waited till the last minute

Breaching a contract in advance on is sometimes called renouncing or repudiating a contract o you announce early your intention to breach o When this happens, if there is a market for a substitute good – in this case,

June corn – then damages would reflect the price of June corn futures at the time you renounced the contract, say, in January.

I could actually buy the futures in January

or I could wait and take my chances

but what happens after that tends not to affect the damages you owe me.

To use another example from two weeks ago…

Suppose one of you agreed a week in advance to sell me a ticket to the Michigan basketball game for $50

At the time we agreed to the deal, there were lots of tickets available for $75

If you breached early in the week, I could have bought a replacement ticket for

$75; so expectation damages would be limited to $25, the damage breaching early did to me relative to performing o If I chose not to buy another ticket in advance, and waited and overpaid on the day of the game, that was a risk I chose to take, but not your responsibility.

But if you waited till the end of the week to breach, a replacement ticket might be more expensive, so damages would be higher

- 5 -

In cases where there is a liquid market for substitutes, there’s little difference between you renouncing our agreement and paying damages, or you going out and buying another ticket on Craigslist to sell to me at our agreed price

If transaction costs are low, the two are equivalent

So when there is a market for a substitute good and transaction costs are low, you are indifferent between breaching and paying damages, and buying and delivering a substitute product.

( SKIP THIS : In well-behaved markets, futures prices are generally assumed to reflect the market’s expectation about what the future spot price of the good will be. That is, if everyone knows there will be a liquid market for tickets at $150 at the end of the week, there’s no reason for them to be selling for $75 early in the week; under certain conditions, futures prices should just be the expected value of the future spot price. So in terms of the expected payoffs, and the incentives to breach, there shouldn’t be a difference whether courts impose damages equal to the futures price at the time a contract is renounced, or equal to the spot price realized at the date of promised delivery.)

When goods are traded that do not have close substitutes, however, the value is sometimes hard to calculate

So courts sometimes impose only reliance damages simply because it’s easier

Renouncing a contract earlier obviously stops the promisee from making further investments in reliance

However, when damages are set lower then the benefits of performing, we’ve seen before that this will lead to inefficient breach

(There are some further complications.

The law on anticipatory breach, and breach following partial performance, are a little bit murky

In some of these cases, renegotiation of the contract may be preferable to outright breach

Again we come to the suggestion that efficiency demands enforcing renegotiated contracts as long as both parties wanted it enforceable at the time of renegotiation.)

- 6 -

Last new topic for contract law: Repeated Games

Nearly everything we’ve done so far has assumed a one-shot interaction

that is, we’ve been assuming that the parties to a contract are only interested in maximizing their gain from that one particular contract,

and are not concerned with any future interactions with the same partner.

Of course, in many cases, this is not true

Example. There’s a coffee shop near my house, and I go there several times a week.

One day, I forget my wallet, and ask if I can still buy a cup of coffee and a muffin, and pay them back the next day

They say yes, and I show up the next day with the money. Why?

(Seems pretty obvious to any reasonable people, less so to an economist.)

An economist would say:

The reason I pay them back is that I want to keep transacting with them in the future

And the value I expect to get from those future transactions is worth more to me than the $3 I could save by breaking my promise now

And the reason they trusted me is that they expected this would be the case.

From a theoretical point of view, repeated games can be very hard to analyze, because a lot of different things can happen

But one of the things that can happen is that we can cooperate in a repeated game, even if we could not cooperate in the same one-shot game.

Let’s go back to the original agency game we did a couple weeks ago.

You choose whether to trust me with $100, which I can double by investing it; and then I decide whether to keep the $200 or return $150 to you and keep $50 for myself

But now, suppose there is the possibility of playing the game more than once.

In particular, suppose that each time we play the game, there is a 10% chance it’s the last time we play, and a 90% chance that we get to play again.

- 7 -

Think about my incentives to repay your money or keep it for myself

If I keep it for myself, I get a payoff of $200; but then you’ll never trust me again, so that’s all I’ll ever get

On the other hand, if I give you back your $150, you’ll probably trust me again the next time, and the time after that, and the time after that (provided I keep returning it)

So the value I expect to get out of the relationship is

50 + .9 X 50 + .9^2 X 50 + .9^3 X 50 + … = 50 / (1 - .9) = 500 > 200

So I’m much better off returning your money, since I’ll make more money in the long-run if you keep trusting me

And because of this, it makes sense for you to trust me

The same thing can also happen with a repeated version of the prisoner’s dilemma.

Recall that in the one-shot prisoner’s dilemma, the only equilibrium was for both of us to rat on each other and go to jail for several years

However, if we expect to play the prisoner’s dilemma over and over, it turns out to be an equilibrium to both keep quiet

Actually, what turns out to be an equilibrium is for both of us to do the following: o Keep quiet the first time we play o As long as neither of us has ever ratted on the other, keep quiet o Once either of us has ever ratted, I rat every time we play forever

This is called a “grim trigger” strategy – we play a good (cooperative) strategy, but if either of us every rats, this triggers a “punishment phase” where we are unable to cooperate

The threat of moving to this punishment phase keeps us both quiet, even though either of us would gain in the short-term by ratting each other out.

So in the prisoner’s dilemma, or the agency game, if the game will be played over and over, it’s possible to get cooperation.

Similarly, in situations where contracts cannot be enforced, repeated interactions with the same parties can lead to voluntary cooperation.

Even when you won’t always be transacting with the same person, transacting within a small community, where people are aware of your reputation, leads to a similar incentive.

- 8 -

The Friedman book mentions an article by Lisa Bernstein on diamond dealers in New

York. To quote:

Buying and selling diamonds is a business in which people routinely exchange large sums of money for envelopes containing lots of little stones without first inspecting, weighing, and testing each one.

The New York diamond industry was at one time dominated by orthodox Jews, forbidden by their religious beliefs from suing each other – making it a trust-intensive industry conducted almost entirely by people who could not use the legal system to enforce their agreements. While the industry had become more diverse by the time

Bernstein studied it, dealers continue to rely almost entirely on private mechanisms to enforce contracts – in part for religious reasons, in part to maintain privacy, in part, perhaps, because those mechanisms functioned better than the courts.

At the center of the system is the New York Diamond Dealers’ Club, which arranges private arbitration of disputes among diamond merchants. Parties to a contract agree in advance to arbitration; if, when a dispute arises, one of them refuses to accept the arbitrator’s verdict, he is no longer a diamond merchant – because everyone in the industry now knows he cannot be trusted. Similar arrangements exist elsewhere in the world and exchange information with each other. Presumably the amount diamond merchants are willing to risk on a single deal depends in part on how long the other party has been involved in the industry and thus how much he would lose if he had to leave it.

Recall that in the first couple lectures on contract law, we introduced a number of pronouncements from Cooter and Ulen, including:

The first purpose of contract law is to enable cooperation , by converting games with noncooperative solutions into games with cooperative solution

Considering the effect of repeated games, Cooter and Ulen add a sixth one to the list:

The sixth purpose of contract law is to foster enduring relationships, which solve the problem of cooperation with less reliance on the courts to enforce contracts.

We saw with the agency game that one way to allow for cooperation was to introduce enforceable contracts

Repeated interactions, or enduring relationships, give another way to get cooperation in what seems like a game with a noncooperative solution

- 9 -

The textbook gives a couple of examples of how courts sometimes try to foster enduring relationships:

By assigning legal duties to relationships that arise out of contracts o example: a bank has a fiduciary duty to its depositors which goes well beyond the terms they agree to on the account o a franchisee who runs a local McDonalds has certain duties to the franchisor o These duties are meant to encourage an enduring business relationship.

Similarly, courts sometimes treat long-term business relationships differently o encouraging the parties to “repair the relationship” rather than simply ruling on the merits of the dispute. endgames

So we’ve seen that repeated interactions and reputation can solve the agency problem and lead to cooperation

But there’s also a potential problem with this

In the examples so far, we’ve assumed that we don’t know how long we’ll keep interacting, but that it might go on indefinitely

However, if there is a particular date when we know our relationship will be over for sure, this can lead to a problem.

Suppose we are going to play the agency game once a month for five years – that is, we’re going to play 60 times

Clearly, getting $50 60 times is much better than getting $200 once, so it seems there should be no problem with getting me to return your money early on in the interaction.

However, think about the problem from the other end.

The last time we play, there’s no longer any future gain if I return your money, since we already know it’s our last time playing.

Given that, you expect me to steal the money you give me in game #60, so you don’t lend me the money.

- 10 -

But now think about game #59

We both know that we won’t cooperate in game #60 – that’s true regardless of what happens in game #59.

So what happens in game #59 doesn’t affect future play

So once again I have no reason to return your money, so I keep it; and you expect this, so you don’t trust me.

But now if we don’t expect to cooperate in game #59 or #60, there’s no reason for you to trust me in game #58.

And so on.

So in a finitely repeated game, cooperation can unravel from the back, and we can fail to cooperate form the very beginning!

This is referred to in Cooter and Ulen as the “ endgame problem ”

Once we know there is a finite end date to our interaction, cooperation can unravel

They discuss an example where this happened: the collapse of communism across much of eastern Europe in 1989.

Communism was believed to be much less efficient than capitalism

But when central planning was replaced by markets, this actually led to a decrease in growth rather than the anticipated increase. Why?

Under communism, a lot of production relied on the black market, or the semilegal gray market.

Since these transactions weren’t protected by law, they relied on long-term relationships to accomplish cooperation.

However, the fall of communism, and the uncertainty that came with it, upset these relationships, causing lots of important cooperation to break down.

So while repeated interaction gives us a way to cooperate without relying on courts to enforce contracts, having a definite end date to the interaction can spoil it.

Keep in mind, though, that to sustain cooperation, the game doesn’t have to actually go on forever; it just has to be possible at each stage that it might continue.

The probability the game will be played again is like a discount factor – you discount the future gains by the probability they will occur

As long as this probability is not too low, the possibility of future gains may still be enough to sustain cooperation.

- 11 -

So that’s contract law.

I’ll save recap till after spring break:

We motivated contract law by looking at the agency game – if you can’t trust me to return your money, we miss out on a valuable investment opportunity

Contracts give a way for a promise to be legally binding , allowing us to cooperate in instances where we could not have otherwise

The first purpose of contract law: to enable cooperation

We introduced the Bargain Theory of contracts , under which a promise is binding if it was given as part of a bargain, which requires three elements, offer, acceptance, and consideration

We introduced the principle that unlike the Bargain Theory, efficiency requires enforcing a promise if both the promisor and the promisee wanted it to be enforceable when it was made

We gave an example of how private or asymmetric information can disrupt trade and cause inefficiency; second purpose of contract law is to encourage efficient disclosure of information

We introduced the idea of efficient breach o Breach is efficient when the promisor’s cost of performing

is higher than the promisee’s benefit from performance o Third purpose of contract law is to secure optimal commitment to performing o Expectation damages leads to efficient breach

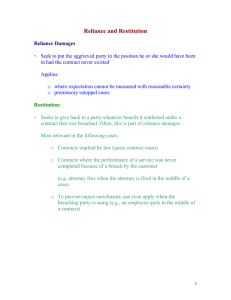

We introduced idea of reliance investment o Investment by the promisee which makes performance more valuable o Fourth purpose of contract law is to secure optimal reliance o When expected gains from reliance are included in expectation damages, we get efficient breach but overreliance o When expected gains from reliance are excluded from expectation damages, we’ll get efficient reliance but excessive breach o Cooter and Ulen propose modifying expectation damages to cover gains from only efficient reliance – nice theoretically, hard practically o Courts tend to reward only foreseeable reliance

- 12 -

We introduced the notion of default rules – rules that cover gaps in contracts o Two approaches: Cooter and Ulen: set default rule to rule that is efficient in most cases , so most parties can save transaction costs o Ayres and Gertner: in some cases, use penalty defaults , to encourage information disclosure by better-informed party o Famous case of Hadley v Baxendale as an example

Baxendale (shipper) is likely the efficient bearer of the risk of delay, since he can take steps to avoid it

But the ruling penalized Hadley (the miller) for not disclosing how urgent the shipment was – to give an incentive to provide that information

Also discussed a few immutable rules , or regulations

Next, we looked at a number of situations where a contract would be invalidated/not enforced, and economic reasons for why o Contracts which derogate public policy o Incompetence (but not drunkenness) o Dire constraints – duress and necessity

Contracts extracted under threat of refusing to create value are enforceable; contracts extracted under threat of destroying value are not

Contracts renegotiated under duress are not enforceable; contracts renegotiated under changed circumstances are o Impossibility

Efficiency requires assigning the liability for impossibility to the party that can bear the risk at the least cost (either by mitigating it, or by spreading it out over many transactions) o Misinformation: fraud , failure to disclose , frustration of purpose , mutual mistake (but not unilateral mistake)

Efficiency often requires enforcing contracts which unite knowledge and control , not those which separate knowledge and control

To give an incentive for discovery, efficiency generally requires enforcing contracts based on one party’s knowledge of productive information , especially if that knowledge was the result of active investment ; but efficiency need not reward purely redistributive information o Vagueness

In general, this can be seen as a penalty default – by refusing to enforce vague contracts, the courts force parties to be more clear o Adhesion and unconscionability (lesion)

- 13 -

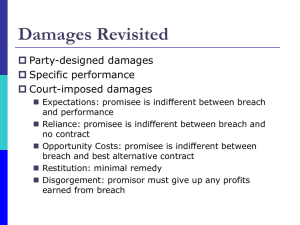

Next, we looked at remedies, among them: o Expectation damages o Opportunity cost damages o Reliance damages o Restitution, disgorgement, specific performance o General unenforceability of penalty clauses in contracts

We looked at the effects of different remedies on decisions to breach, to invest in reliance, and to invest in performance o Like with injunctions and nuisance damages, with low transaction costs , any remedy can lead to efficient breach through renegotiation o But with high transaction costs, only expectation damages lead to efficient breach o When damages < benefit from performance, inefficient breach, or underinvestment in performance o When damages include any expected gains from reliance, overreliance o (“ Paradox of compensation ” – no damage rule that achieves efficient levels of everything. Anti-insurance – one cute attempt to solve the problem.)

And finally, today, we covered repeated games, and the sixth purpose of contract law, to foster enduring relationships, which solve the problem of cooperation with less reliance on courts for enforcement

Return Midterms

Median, mode = 71, mean = 72, std dev = 13

Very roughly (with disclaimers): o 90+ is an A o 80-89 is an AB o 65-79 is a B o 58-64 is a BC o 50-57 is a C

Homework on contract law due third lecture after spring break

Chao will teach section Thursday, 1 p.m., here

No section meetings on Friday

Enjoy spring break!

- 14 -