Alexander Ruch English 1010 Tulane University, Spring 2013

advertisement

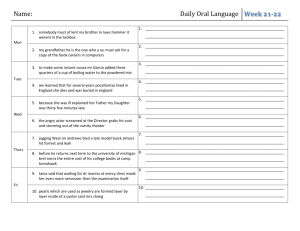

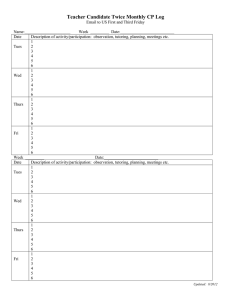

Alexander Ruch aruch1@tulane.edu Office: 202 Norman Mayer Office Hours: Mon 2-4, T 4:45-5:45, Th 3:304:30, and by appointment English 1010 Tulane University, Spring 2013 Sec 31: T Th 12:30-1:45, Gibson 400D Sec 34: T Th 2:00-3:15, Gibson 400D Sec 38: T Th 6:00-7:15, Gibson 308 English 1010: Writing Course Description English 1010 is designed to help you write clearly and organize complex arguments that engage in a scholarly way with expert knowledge. Toward that end, you will learn to conduct independent bibliographic research and to incorporate that material appropriately into the sort of clear, complex, coherent arguments that characterize academic discourse. Specifically, you’ll learn that: To write clearly means that you must take a piece of writing through multiple drafts in order to eliminate any grammatical errors or stylistic flaws that might undermine the author/audience relationship; To write with meaningful complexity, you must learn to practice a variety of invention strategies (e.g., the five classical appeals, freewriting, reading and analysis, and library research) and to revise continuously the materials generated by these methods; To make coherent arguments without sacrificing complexity, your practice of revision must be guided by certain principles of style and arrangement, and you must grow adept in the genre of argument itself through work with models and templates established by standard persuasive rhetorics; To create effective arguments, you must cultivate strategies for positioning texts against each other to familiarize yourself with the arguments of others before developing your own claims, and grow adept at using warrants, evidence, counter-claims, and other rhetorical tropes to craft your own arguments. You will learn strategies for active, critical reading, strategies for deciphering why a text might be arranged a certain way and what that arrangement might mean; To conduct effective research means utilizing the library, evaluating sources, and incorporating the work of others into your texts using the proper conventions of citation endorsed by the Modern Language Association (MLA). You will also learn strategies and conventions for summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting others’ work to support and develop original claims. To develop the skills mentioned above, English 1010 balances seminar-style discussions with heavy student participation; brief lectures; hands-on productive work in writing workshops and guided “lab” exercises; and regular one-on-one conferencing with your professor. 2 Section Description: Telling Stories Telling, hearing, reading, writing, and responding to stories are fundamental human activities, as basic to our existence as eating or sleeping. We hear stories whenever we turn on the news, tell stories whenever we have job interviews, go on dates, or compose academic papers. In this course, we will explore different ways of understanding this need to tell stories, focused through attention to one of the oldest oral and literary genres: the fairy tale. To do this, we will examine a variety of fairy tales, from the Grimms’ collections of oral peasant stories to animated Disney films and recent fairy tale films for adults. Along the way, we will engage with different approaches to fairy tales, from cultural history to literary analysis, developmental psychology, and feminist criticism, to examine how these different lenses elucidate different aspects of and problems pertaining to these tales. In this course, we won’t just passively read what others have written about fairy tales, but engage with that writing to develop our own thoughts about what it means to read and tell stories. By writing generously about, with, and sometimes against others to enter into a larger conversation (what Joseph Harris calls “rewriting”), we will hone our skills at making academic arguments that speak to others. We will become more experienced at identifying different kinds of arguments, and in different ways of drawing those arguments into our own to create more engaging and persuasive writing. We will conduct academic research, and learn about the reasons behind the conventions we use to make our claims both compelling and responsible to a larger academic community. We will examine the traits that make prose clear, concise, cohesive, and coherent, and learn practical ways to revise prose with those traits in mind. We will also think about the ways that academics tell stories as ways to advance their own ideas, and try some of these narrative strategies out in our own writing. Outcomes and Policies Outcomes: Students will learn how to write clearly and how to develop complex, coherent arguments that engage with expert knowledge through independent scholarly research and correct citation of sources. Attendance: Students in English 1010 develop skills that will serve them for their rest of their academic and professional lives. What’s more, no matter how well a student writes, he or she can and should always cultivate these skills yet further. To do this, students must come to class, participate in class activities, and sustain positive, productive membership in the classroom community of student-writers. Thus, attendance, as well as punctual arrival and participation are absolutely essential; moreover, cell phones must be silenced, and text-messaging and emailing are strictly forbidden, for these disruptions, as with tardiness, can be counted as absences. When a student absence results from serious illness, injury or a critical personal problem, that student must notify the instructor and arrange to complete any missed work in a timely fashion. Students are allowed, over the course of the semester, to miss the equivalent of one week of class without penalty. Thereafter, students will lose one-third of their final grade for every unexcused absence from class. Once a student has accumulated the equivalent of three weeks of unexcused absences, he or she has automatically failed the class. In order to enforce the attendance policy, the instructor will document the dates of every student’s unexcused absences and file an “Absence Report Form” for any of their students who accumulate four unexcused absences. These forms are sent to the student and the student’s dean (the instructor retains the third copy). If the student’s attendance problem results in his or her failing the course, 3 the instructor should file a second “Absence Report Form” recommending that the student be withdrawn from the course with an F. Along with full bsence, tardiness is a serious issue in a seminar-style course. It disrupts the class, and is rude to me and to your fellow students. I ask that you arrive on time as a courtesy to all involved, but also enforce punctuality with a formal policy. You will be marked absent if you are more than 5 minutes late to a class meeting. These kinds of absence are included in the count described above, and can very quickly drag your grade down. Assignment Protocol and Late Policy: Unless otherwise noted on the class schedule, all assignments are due electronically on Blackboard prior to the first course meeting of that week (so, for example, an assignment for a Tu/Th class must be uploaded to Blackboard prior to the Tuesday class meeting). Late papers will be docked one letter grade per calendar day (not class meeting); late short assignments will not be accepted without medical documentation. Academic Dishonesty: This link will take you to the Newcomb-Tulane Code of Academic Conduct: http://college.tulane.edu/code.htm. All students must take responsibility for studying this code and adhering to it. We will devote some time in class to it. Our purpose, in these discussions, will be not only to teach you how to avoid plagiarism and how to cite sources, but to initiate you into the contemporary discussion of intellectual property and the nuanced dynamics between individuality, authorship, and what’s sometimes called intertextuality, so that you can make informed and thoughtful choices about your writing for the rest of your university career and later in life. The Grade of “Incomplete”: If a student has a legitimate excuse for being unable to complete all of the work for a course, the instructor can give that student an “I” (Incomplete) on the final grade sheet. If the student does not complete the work and the instructor does not change the grade, however, that grade will revert to an F. The deadline for addressing incompletes varies each semester but is usually about one month after the final exam period. Before a student is given an “I,” the instructor will confirm with the student – in writing – exactly what the student needs to finish and retain a dated copy of this correspondence in the event that the student misses the deadline and then expresses confusion about the new grade of “F.” Students with Special Needs: Students who need special help with the course, such as note-taking, free tutoring, additional time and/or a distraction-reduced environment for tests and final exams, may contact the Goldman Office of Disability Services (ODS), located in the Center for Educational Resources & Counseling (ERC). It is the responsibility of the student to register a disability with ODS, to make a specific request for accommodations, and to submit all required documentation. On a case-by-case basis, ODS staff determines disability status, accommodation needs supported by the documentation, and accommodations reasonable for the University to provide. University faculty and staff, in collaboration with ODS, are then responsible for providing the approved accommodations. ODS is located in the ERC on the 1st floor of the Science and Engineering Lab Complex, Building (#14). Please visit the ODS website for more detailed information, including registration forms and disability documentation guidelines: http://tulane.edu/studentaffairs/erc/services/disabilityserviceshome.cfm. Grade Breakdown Short Weekly Writing Assignments: 20% (5 x 4% each) 4 Paper 1: Analysis 20% Paper 2: Argument 20% Paper 3: Research 20% Paper 4: Major Revision 20% Grading Standards and Expectations The course writing assignments fall into two broad categories: short, low-stakes assignments that are designed to give you practice performing different “moves” involved in academic writing, and longer papers that ask you to synthesize the moves (and often the actual substance of the shorter assignments) into more complex yet coherent wholes. The short writing assignments are either acceptable or not, and thus receive either full or no credit. The longer papers will receive letter grades according to the following grading standards: The A Paper ... is characterized by the freshness, ambition, maturity, coherence, and complexity of its content. Its claims are stated clearly and effectively, supported well, with relevant nuances interpreted and delineated in ways that go beyond the obvious. It manifests a distinctive voice that explicitly engages a meaningful rhetorical context and, in turn, an actual audience. It situates itself thoroughly among assigned readings, perhaps even key, related texts in public discourse. It effectively balances the specific and the general, the compelling detail and the larger point, personal experiences and direct observations of the outer world. It grows out of large-scale revisions (both in terms of content and structure). It not only fulfills the assignment, but inventively uses the assignment as an occasion to excel. Its only errors, if any, are purely typographical and quite rare. Finally, it manifests a certain stylistic flair – the bon mot, the well-turned phrase, the significant metaphor – that helps to make it, for the reader, memorable. The B Paper ... is characterized by content that is a relatively familiar, less daring, less integrated or a little simpler than one might hope. Its claims could use more support or more exploration, or could perhaps be stated more directly. Its voice could be more distinct and it could situate itself more engagingly in the rhetorical context and go farther to reach its audience. It could do more with the assigned readings, create a better balance between specific and general, detail and idea, personal anecdote and larger point. It fulfills the assignment, but in a way slightly perfunctory. It makes very few errors and shows no systematic misunderstanding of the fundamentals of grammar, but its overall structure might appear somewhat uneven. Finally, it could benefit from more large-scale revision and from more careful attention to its style at the sentence-by-sentence level. The C Paper ... is characterized by overmuch dependence on the self-evident, is dotted with cliché, and is inadequately informative. Its essential point is uninteresting or only hazily set forth or developed aimlessly. It has no particular voice, nor any significant sense of context or audience, nor any real engagement with other texts. In terms of the dynamics between detail and idea, it seems to lose the forest-for-the-trees or vice versa. It fulfills the assignment but does so in a way wholly perfunctory. It has grammatical errors that significantly disrupt the reading experience. It has not been sufficiently revised. The D Paper ... is characterized by minimal thought and effort, which shows through the absence of a meaningful, central idea or the lack of any controlled development of that idea. 5 It fails to fulfill some key aspect of the assignment. It makes no meaningful use of other texts nor ever situates itself in any sort of context. It needlessly offends its audience. Its sentences and paragraphs are both built around rigidly repeated formula and soon become predictable. It is riddled with error. It has apparently never been revised. The F Paper ... is characterized by plagiarism or lateness or a total misunderstanding of the assignment or is simply incomprehensible owing to a plethora of error or desperately poor organization. It has not only not been revised – it really hasn’t been begun. For a more detalied breakdown of how these grades are computed, please see the sample generalized rubric at the end of this syllabus. Course Texts Readings are available in PDF on Blackboard. 6 Class Schedule Date Day Read In-class Turn in Intro / SA1 SA1: Writing about Story 15-Jan Tues 17-Jan Thurs Strabo, "The Egyptian Cinderella" (1), Grimms, "Cinderella" (5); Miller, "A Tone Licked Clean" (6) Discuss "Cinderella" / Summary 22-Jan Tues Bettelheim, "The Struggle for Meaning" (17), Rowe, "Feminism and Fairy Tales" (21) Discuss Bettelheim & Rowe 24-Jan Thurs Yeats, "The Stolen Child" (1) 29-Jan Tues P1 Tales (Perrault, "Donkey Skin" [7]; Straparola, "The Pig Prince" [6]) Close Reading Exercise Discuss P1: Analysis Paper 31-Jan Thurs Grimms, "Hansel and Gretel" (6); Bettelheim, "Hansel and Gretel" (8) 5-Feb Tues 7-Feb Thurs 12-Feb Tues MARDI GRAS NO CLASS 14-Feb Thurs Zipes, "Breaking the Disney Spell" (22) 19-Feb Tues Craven, "Beauty and the Belles" (18) Begin Argument Unit / Logos, Ethos, Pathos Discuss Readings 21-Feb Thurs Play through ir/rational Redux at http://www.newgrounds.com/portal/view/598731 26-Feb Tues 28-Feb Thurs 5-Mar Tues Fallacies 7-Mar Thurs 12-Mar Tues 14-Mar Thurs Style: Flow and Emphasis Screening (Pan's Labyrinth--time and location TBA) Research Question 19-Mar Tues Analysis and Critical Lens: Ways of Appraoching Analysis Style: Clarity and Conciseness Class Cancelled for Individual Meetings View Pan's Labyrinth SA3: Close Reading of a Paragraph from P1 tale P1 Draft SA4: Short Analysis of Reading Toulmin Model Main Claims Richardson, "High Heels: Are They Worth It?" (10) SA2: Summary of Bettelheim or Rowe P1 Argument Structure / Revisit Toulmin CLUE Library Session P2 Draft 7 Date Day Read In Class Turn In MLA: Citation details / Recursive research balance sheet SA5: Research Question and 3 Secondary Sources 21-Mar Thurs 26-Mar Tues SPRING BREAK NO CLASS 28-Mar Thurs SPRING BREAK NO CLASS 2-Apr Tues 4-Apr Thurs 9-Apr Tues 11-Apr Thurs 16-Apr Tues 18-Apr Thurs 23-Apr Tues 25-Apr Thurs 30-Apr Tues From Research to Argument Class Cancelled for Individual Meetings Style: Balance Peers' Drafts Peers' Drafts P4 due on designated final date/time Peer Review P3 Drafts Discuss Revision/P4 Workshop Proposals Style: Figurative Language and Voice P2 Draft of P3 Proposal for P4 Class Cancelled for Individual Meetings P4 Draft Peer Review/Wrapping Up P3 8 Sample Generalized Grading Rubric Each paper will have it’s own rubric and points will be determined accordingly. Here is an example of what a typical rubric might look like: Points 20 10 Category Assignment 20 Main Claim 10 10 10 10 10 20 20 10 10 Argument 5 5 Significant Comprehensive Complex 5 Compelling Within paragraphs 10 Paragraph to paragraph 2 Clarity and conciseness 2 Flow 2 2 Emphasis Balance 2 Figurative language and voice Style Formatting 2 4 Grammar 10 100 Contestable Interpretive Specific Based in fact Coherent Organization 10 Total Description Assignment-specific grade is sum of breakdown Assignment-specific objectives 5 4 10 Breakdown Document Citations Work Cited All correct Main claim grade is the lowest of breakdown grades could reasonably be argued against goes beyond recognized facts to present original insight defines key terms and criteria in sufficient detail interpretations arise from factual basis from which evidence is drawn relevance of claim to reader is either obvious or explained Argument grade is sum of breakdown provides sufficient evidence and analysis of that evidence goes beyond commonplaces and entertains objections and complications maintains focus on main claim, and explains how subclaims relate to the whole demands interest and effectively links evidence and reasoning Organization grade is sum of breakdown individual paragraphs develop logically to present coherent points movement among topics develops logically and clearly Style grade is sum of breakdown, and is weighted toward current style objectives says what needs to be said economically, avoiding empty verbiage sentences and paragraphs connect ideas by moving from familiar to new material sentences effecitvely direct attention to important points sentences direct readers' attention to important comparisons or contrasts sentences engage readers’ imagination Formatting grade is sum of breakdown margins, headers, footers, etc. are appropriate for the style used in-text citations and work cited are both clear and accurate list of references is properly formatted and complete Grammar grade is 10 for full correctness, and reductions for specific issues will be noted in breakdown