BRIDGING THE PREVENTION GAP: PREVENTION PROGRAMS AND SHARED

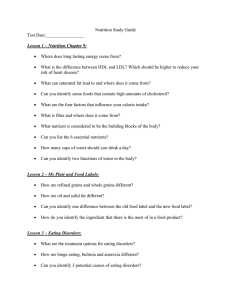

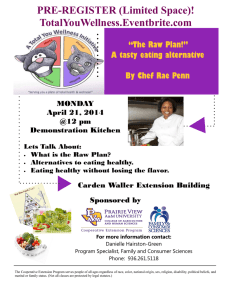

advertisement