AFRICA THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 31 NO. 1, 2008

advertisement

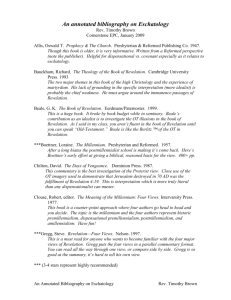

AFRICA THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 31 NO. 1, 2008 Published by the Theological Faculty Makumira University College Tumaini University A REVIEW OF CATHOLIC ESCHATOLOGY Pius Oyeniran Ahioje Introduction Christianity is said to be a religion that revolves in eschatology. Many scholars have even ventured to say that eschatology is central to every authentic religion. As Peter C. Phan notes: As a rule, religions claim to offer answers to questions regarding the beyond and to help their followers attain ultimate happiness variously referred to as heaven, paradise, eternal life, or nirvana. Christianity is no exception. One of the central tenets of its creeds proclaims that its founder, Jesus Christ, who died and was raised to life will come again to judge the living and the dead and that there will be the resurrection of the dead and life everlasting.1 Despite the fact that Christianity is regarded as eschatological in essence, a religion of hope, based on the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, it would seem that with the likely exception of Lent, Easter and funerary liturgical services, eschatological talk rarely features in Christian preaching and discourse in contemporary times. In 1985, Vittorio Messori noted that: Christian eschatology (insofar as it is mentioned at all) has been reduced to 'heaven' alone, and even the word itself causes problems; it is written in quotation marks, and here loo there are people who would reduce it to the level of an oriental myth.2 One's finding is that the situation has not changed, and so one feels the need to present t h i s review. The aim is to discover what may have gone wrong, and to re-present the original Christian _____________________ 1Peter C. Phan, Responses to 101 Questions on Death and Eternal Life (New York Mahwah, N.J., Paulist Press, 1997), p.16. 2 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger will, Vittorio MEssori, The Ratzinger Report- An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985), p.145. eschatological vision, to the extent of one's possibility, toward a better life here on earth, anil full realization of Christian eschatological hope. Materials were gathered mainly through library consultation. Theoretically, the study is expository and somewhat critical. Eschatology in Definitive Terms Messori already indicates a crisis of definition in the quotation cited above, when he notes that some Christians have reduced or restricted the meaning of eschatology to going to heaven alone. He (Messori) rightly remarked that although "any one who reads the Gospels does find first and foremost the Good News, the consoling proclamation of the Father's infinite and immeasurable love, side by side with it we also find in the Gospels the clear affirmation that disaster is possible and that it is not impossible to refuse God's love."3 But he did not present a full definition of the term, "eschatology". Traditionally speaking, the word eschatology connotes elements which include: death, judgment, heaven, and hell. In the words of Richard P. McBrien: Eschatology, in the traditional sense of the word, is the area of theology which is directly concerned, w :ilh the 'study of the last thing(s)' ....... The 'last things' (eschata) are various moments or stages in the final manifestation process: death, particular judgment, heaven, hell, purgatory. Second Coming of Christ, resurrection of the body, general judgment, consummation of all things in the perfection of the Kingdom of God.4 Most of these articles of faith are commonly believed by most Christians. With particular reference to purgatory, A.T. Hanson notes that while belief in it is a common heritage of Christendom dating back to St. Augustine, ensuing abuses "were violently denounced by the Reformers; and the Council of Trent ___________________ 3 Ibid. Richard P. McBrien, Catholicism (Harper San Francisco, 1974), p.1123. 4 was very moderate in its formulation of the doctrine.” 5 MiCatholic Cardinal Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for t h e Doctrine of the Faith, Joseph Rat/.inger, the current Pope, once commented that belief in purgatory had waned because "all of us today think we are so good that we deserve nothing less than heaven!" He concluded by saying, "If purgatory did not exist, we should have to invent it." He held, and one would agree with h i m that most human beings appear to have one thing or another to In purged of. The issue of the "Second Coming of Christ" that is listed in the indented material above also needs some clarification While a number of "religious groups (Anabaptists, Seventh-Day Adventists, Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, etc)", 7 see it in terms of Millenarianism, some others, such as the Roman Catholic Anglican and Methodist Churches, conceive it as "the general judgment."8 The principal point here, however, is that no Christian denomination, properly so called, is known to deny the reality of the last judgment, the pamusia, eschatologically speaking. In Roman Catholic eschatology, there used to be what was known as Limbo. It was popular at a time when it was thought that an unbaptised baby or infant who was guilty of the Original Sin could not go directly to heaven upon death. Such an individual, it was believed, would have to be purified first in Limbo, while purgatory constituted the purification centre for adults. In the course of time, it was theologically thought that the fate of such babies and infants should be left to God to decide. Messori quotes Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger as saying, for instance, that: ______________ T. Hanson, "Hope, the Christian”, in Alan Richardson (ed), A Dictionary of Christian Theology (London: SCM Press Ltd., 1979), p. 160. 6 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger with Vittorio Messori, ibid., p. 145f 7 William C. McKulden, "Millenarianism", in Michael Glazier and Monika K. Hellwig (eds), The Modern Catholic Encyclopedia (Collegeville, Minnestoa: A Michael Glazier Book, 1994), p. .572. 8 Robert C. Broderick, The Catholic Encyclopedia (Nashville: Thomas Nelso Inc. Publishers, 1975), p. 387. 5A. 'Limbo was never a defined truth of faith. Personally and here I am speaking more as a theologian and not as Prefect of the Congregation I would abandon it since it was only a theological hypothesis. It formed part of a secondary thesis in support of a truth which is absolutely of first significance for faith, namely, the importance of baptism.'9 Indeed it is not only Ratzinger who "would abandon it". In the words of Andrew Greeley, "Limbo has pretty much gone down the drain".10 So may it be. It would seem that controversy is surrounding another eschatological concept, namely, "hell". Michael Schmaus notes that although "Scripture frequently uses the word fire when speaking of hell", and that is associated "with such expressions as wailing and gnashing of teeth and the worm that does not die.... It would be a mythical concept of hell to imagine the damned pressing upon God and God hurling them back with the words Too late'."" In a similar vein, David L'. Edwards maintains that he himself is among those Christians. who would say that "the traditional imagery of hell which is derived from the fires and the worms which consumed, the rubbish dumps in the valley of Gehenna outside Jerusalem", should give way to "tin- God who is love", and so "may be expected to act like the lather in the parable of the prodigal son". He holds further that "It seems wrong to teach that no repentance is possible alter death", because "like the soldiers who crucified Jesus, many people who do wrong 'do not know what they are doing before they die."12 It is remarkable that while Schmaus is a Catholic, Edwards is an Anglican theologian, they have no doubt that God, who is pure love and kindness, may not be linked to a merciless _____________________ 9 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger with Vittono Messori, ibid., p. 147. Andrew Greeley, Everything You Wanted to Know About the Catholic Church but Were Too Pious to Ask (Chicago, Illinois: The Thomas More Press, 1978), p. 99. 11 Michael Schmaus, Dogma 6::Justification and the Last Things (London: Sheed and Ward, 1977), pp. 256 & 258. 12 David L. Edwards, What is Catholicism'.' An Anglican Responds to the Official Teaching of the Roman Catholic Church. (London: Mowbray, 1994), p. 28f. 10 conception of hell. At the same time, many other theologians, such as Andrew Greeley. though they acknowledge the difficulties involved, argue nevertheless, that: To deny the existence of Hell means to deny the importance of human freedom and to reduce the choices we make during our life times to irrelevance. One can forget about the hellfire, the sulphur, the Dantesque imagery: one still must acknowledge, it seems, the possibility of loss, of sell-chosen isolation, alienation, separation. Whether such folk get another chance or not is something best left to the mercy of God. Obviously, after all the reasonable digression, the mercy of God is s t i l l put into consideration in the final sentence of the submission. Yet, human beings face one form of hell or another, as applicable to persons who face excruciating pain, police torment or martial torture; marital, family or work difficulties, rightly or wrongly. And so, the concept of hell may not be dismissed with a wave of the hand, as Greeley, and those in the same school of thought with him try to explain. In other words, the fear of hell may sti ll be the beginning of wisdom, temporarily and eschatologically speaking. The direct antonym of hell is, of course, heaven. It does not seem that any theologian of note has defined it (heaven) in any way that is radically different from the traditional conception of it. In an academic work by Michael Schmaus, one reads that "heaven" does not necessarily imply "that God's existence is confined to a specific place", but that it is "a word symbolizing God." 14 Another scholar, David L. Edwards, quotes The Catechism of the Catholic Church (published in 1994) approvingly, in respect of the meaning of heaven, saying: We are wisely told that 'this mystery of blessed communion with God and all who are in Christ is beyond all understanding and description' although "Scriptu re speaks of it in images: life, light, peace, wedding feast, wine of the kingdom, the Father's house, the heavenly Jerusalem, paradise'(1027). 15 ______________________ 13 Andrew Greeley, ibid., p. 99. Michael Schmaus. ibid., p. 261. 15 David L. Edwards, ibid., p. 29. 14 This position appears unassailable. And beyond that, this section on clarification of the concept of eschatology cannot proceed. Eschatology in Old Testament Context It is generally held among many biblical theologians that the Old Testament (henceforth OT) does not contain a systematically discussed eschatology. and that it does not have much to say about afterlife. As Peter C. Phan notes, for instance: Of course, the Old Testament (which is seven books larger than the Hebrew Scriptures) does speak about death, but it is rather reticent about the afterlife. No hope of individual survival after death is expressed in the Old Testament except in some late texts written probably in the second century B.C.C."' (The term, "seven books larger" refers to the Catholic volume of the OT). With regard to the subject under discussion, it is obvious that in the last pail of the quotation, the OT is not without its own teaching on life after death. Essentially, two forms of eschatology are identified in the OT. In the first instance is the prophetic eschatology, which is said to derive from the futuristic proclamations by many prophets. This form of eschatology is perceived to be mostly earthbound. As Dermot A. Lane notes: The future promised by the prophets is a future about life in this world; an end to poverty and injustice among the chosen people, the creation of peace on earth among nations, and the introduction of new harmony between people and nature.17 The content of this quotation explains why Lane notes further that "many of the concerns of OT eschatology overlap with the concerns of twentieth century eschatology." 18 One can note. ___________________ 16 Peter C. Phan, ibid., p. 32. Dermot A. Lane, "Eschatology", in Joseph A. Komonchak, Mary Collins, and Dermot A. Lane (eds), The New Dictionary of Theology (Bangalore: Theological Publications in India, 1996), p. 330. I8 lbid. 17 without any tear of reasonable contradiction, that the issues of poverty, injustice, strife and lack of peace are still very much relevant for eschatological discourse today, twenty-first century. Primarily, the prophets were concerned with discerning and interpreting God's will for the people of God. As McBrien explains: Prophecy is not primarily a matter of predicting the future (that is the function of an oracle or clairvoyant). But insofar as the prophet offers an interpretation of events and discusses the consequences of one form of action or another, or of a failure lo act. the prophet is indeed concerned with the future.19 Many biblical scholars have tried to explain what is eschatological about the future that features in the message of the prophets. Lane, for instance, notes that the theme of a new creation that developed after the Babylonian exile is a statement of dissatisfaction about the world as it is, and an expression of hope that this world will be transformed by Yahweh. He quotes the book of Prophet Isaiah (65:19) where God is cited as saying that He would create "new heavens and a new earth" and that He would rejoice in Jerusalem and be glad in His people, for there would be "no more weeping and the cry of distress". Lane concludes by adding that although the eschatology of the prophets is "this worldly, with l i t t l e or no reference to what we today would call the next life", it should not be forgotten that "Yahweh is at the centre of 'this worldly' eschatology." "Yahweh is the one who will in the future change our world into a better place to live." 20 Another scholar, Phan, observes that even though "from the literary standpoint it is inappropriate to refer to the prophetic writings as "eschatological literature", nevertheless, it should be noted that "there is a stark contrast between the present age and the age to come" as presented in the message of the prophets. As Phan further notes, "Increasingly, the new age was seen less as a recovery of the ideal past than as a destruction of the present order, ___________________ 19 20 Richard P. McBrien. ibid., p. 261. Derniot A. Lane, ibid., p. 330. an annihilation of God's enemies, and a creation "of a totally new world beyond history and this cosmos." 21 Of course, "annihilation of God's enemies" implies the end of oppression, exploitation, and all inhumanities of human beings to human beings, which are unimaginable in the present order of reality, and can only be conceived as an eschatological possibility. On the whole, it would seem that the prophetic eschatology centres around what is termed "the day of the Lord" (Yahweh). As Lane notes: From the eighth century onwards the prophets begin to point towards a time in the future when Yahweh will judge Israel and the rest of the world. This time is known as the 'day of the Lord,' a time of upheaval and destruction as well as a time of renewal and return to the ways of Yahweh." That seems to be a very good summary of prophetic eschatology. The other type of eschatology that is identified in the OT is apocalyptic eschatology, which is "primarily other-worldly in its concerns", even though within it "there is an emphasis on the transformation of this world into a new reality."23 Etymologically speaking, Phan notes that as a literary genre, the term apocalypse derives "from the Greek apocalypsis, meaning revelation, disclosure." Besides, he quotes John J. Collins, who is said to have studied all the apocalyptical texts from 250 B.C.E. to 250 C. E. as defining apocalypsis as: A genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial, insofar as it involves another, supernatural world.24 With specific reference to connection, Lane notes that: ______________________ 21 Peter C. Phan, ibid., p. 34. Dermot A. Lane, ibid., p. 330. 23 Ibid. 24 Peter C. Phan, ibid., p. 35 22 apocalyptic eschatological The word apocalypse means a special kind of revelation, usually given in symbolic and dramatic language which requires the interpretation of an angel. The main example of apocalypse in the OT is given in the Book of Daniel which was writing the Maccabean crisis. During that time, the Jews were persecuted under the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Jewish laws and practices were suppressed; many were put to death as martyrs for practicing their religion. Within this context the author of the Book of Daniel raises the question of a reward for the righteous. For the first time in Judaism the possibility of life beyond death is explicitly affirmed.25 To buttress the point, Lane quotes from the Book of Daniel, where it is written: And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall wake, some shall live forever, others shall be an everlasting horror and disgrace. And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the firmament; and those who lead the many to justice shall be like the stars (Dan. 12:2-3). The essential message of apocalyptic eschatology seems to be that human hope goes beyond death, and that implies life after death. Thus, the faithful and the just will not die in vain, as reward or punishment (as the case may be) await individuals after death. Although one will presently discuss eschatology in New Testament perspective, it seems necessary to note at this stage, that both the prophetic and apocalyptic eschatologies are illustrated across the Bible, and so, not limited to the OT. With specific reference to ap o calyp tic eschatology, Phan notes that: In the Bible there are two books that belong to this genre, Daniel in the Old Testament and Revelation in the New Testament. Some extracanonical writings also belong t o it, notabl y First Enoch, Second Enoch, Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch, Apocalypse of Ezra, Apocalypse of Apocalypse of Abraham, and Ascension oflsaiah.26 Thai lends in illustrate biblical inter-connectivity in eschatological terms and the diversity of views or opinions that may be found ___________________ 25 Dermot A. Lane, Ibid., p.331. 26 Peter C. Phan, ibid., p.35. here or there. Eschatologically speaking, the Bible seems to be harmonious, to a great extent, as what follows will reveal. The New Testament Eschatology Jesus is, of course, the principal of tin- New Testament (henceforth NT). Since He is said to have come not to abolish the Law and the Prophets, but to fulfill (hem. He can be identified with every authentic message of the Prophets, including the eschatological ones. It is generally believed among Christian that He "is the fulfillment of the prophecies and promises given to the world through the Jewish people." With specific reference to eschatology, S. H. Travis notes that: Jesus look over prophetic and apocalyptic thought-forms, but with a crucial difference: in his ministry the longed-for time of salvation had dawned, the kingdom of God has drawn near (Mk. 1:15). His possession of the Spirit, his miracles and his exorcisms were evidence of this (Mt. 11:2-6; 12:28). Yet the kingdom had not fully come, for, despite the real blessings of God experienced with a new immediacy, evil, death and the ambiguities of life remained. The complete realization of the kingdom lay in the future, at the coming of the Son of Man (Mk. 13:26). The distinctive feature of NT eschatology, found especially in Paul, is thus a tension between what is already known and experienced (because Christ has come), and what is not yet experienced (because Christ is still to come).28 That somehow contradicts C. H. Dodd's concept of realized eschatology. As Travis further notes, "a more balanced synthesis is achieved by scholars such as (). Cullman and R. H. Fuller who have argued that present and future references in Jesus' message of the kingdom must be held in tension".29 That position forms part of the background to the indented quotation above. _____________________ 27 Ronald Lawler, Donald W. Wueri and Thomas Comerford Lawler (eds), The Teaching of Christ: A Catholic Catechism for Mulls (Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor, 1983), p. 178. 28 S. H. Travis, "Eschatology", in Sinclair H. Ferguson and David F. Wright (eds.), New Dictionary of Theology (Leicester: Inter-Versify Press, 1998), p. 228. 29 Ibid., p. 229. Beyond die foregoing, there is a sense in which one must state that the Resurrection of Jesus is pivotal to Christian eschatology. As St Paul notes, "If Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain”, and your faith is also vain" (ICor. 15:14). Yet, historically and academically, as Phan observes: Then- arc some scholars (e.g. T. F. Glasson, Marcus J. Borg, and B. Mack) who would dispute that Jesus' outlook was shaped by Jewish apocalypticism and would argue that Jesus was a Cynic sage rather than a messianic preacher. The great majority of biblical scholars, however, would hold that Jesus stood squarely within the apocalyptic tradition. They point out that the movement with which he associated himself, that of John the Baptizer, was apocalyptic. Furthermore, the movement that issued from him immediately after his death, the earliest Christian community in Jerusalem, interpreted him both as the expected Messiah and the Son of Man and was itself also apocalyptic.30 In consonance with the point made by Phan, Lane notes that the eschatological hopes and expectations of the OT "make up the atmosphere in which the mission and ministry of Jesus is played out", and that "the over-riding horizon of the life of Jesus is the announcement of the Reign of God."31 The German Catholic Bishops' Conference also notes that: At the center of Jesus' ministry there stands his message about the coming of the Kingdom of God. The evangelist Mark summarises this good news in this way: 'Alter John's arrest, Jesus appeared in Galilee proclaiming the good news of God: 'This is the time of fulfillment. The reign of God is at hand! Reform your lives and believe in the gospel!' (Mk. 1:14-15)'32 In point of fact, the Reign or Kingdom of God, as preached by Jesus, has both its apocalyptic and prophetic aspects, eschatologically speaking. In apocalyptic terms, the German Bishops' Conference notes that "The New Testament deliberately uses the 'Kingdom of heaven' as synonymous with the 'Kingdom _______________________ 30 31 Peter C. Phan. ibid..p. 39. Dermot A Lane, ibid., p. 331. German Bishops’ Conference, A Catholic Catechism for Adults: The Church's Confession of Faith (San Francisco: Communio books, 1987), p. 124. 32 of God'," and that "God alone is the heaven of man, the fulfillment of his deepest wishes and longings." 33 In prophetic eschatological perspective, Albert Nolan notes that: The good news of the kingdom of God was news about a future state of affairs on earth when the poor would no longer be poor, the hungry would be satisfied and the oppressed would no longer be miserable. To say ‘th y kingdom come' is the same as saying 'Thy will be done on earth as ii is in heaven' (Ml. 6:10 par.) 34 At the same time, as John Onaiyekan notes, "the two meanings of kingdom, heavenly and this worldly, future and present, already and not yet, are not totally separate." As he emphasizes, "Both are under God's own control", and "the kingdom here is a preparation for the kingdom in the world lo come."35 Understandably, the preparation hinges on doing God's will on earth as in heaven. The question should be asked: In what does the will of God consist? According to Thomas Aquinas, "God's will is made manifest to free creatures by their reason and by revelation." He notes, "for instance, the Ten Commandments are an expression of God's will which is manifested by revelation; the same Commandments are manifested by reason, for a studious man could think them out."36 In an obvious reference to the words of Jesus, Seef Konijn likewise notes that: One thing in life, and only one, is paramount and that is love. This is really the only commandment there is. The other person's well-being and my own. In so far as I bring happiness to another, I find it myself. That is the basic norm: love. All other commandments and laws must lead back to that.37 ____________________ 33 Ibid., p.92. 34 Albert Nolan, Jesus Before Christianity (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1991), p. 46. 35 John O. Onaiyekan, Thy Kingdom Come: Democracy and Politics in Nigeria Today: A Catholic Perspective (Abuja: Gaudium et Spes Institute, 2003), p. 14. 36 Thomas Aquinas, la, q19, all (Cf.) also Paul J. Glenn, A Tour of the Summa (Rockford, Illinois: TAN Books and Publishers Inc., 1978), p. 23. 37 Seef Konijn, The Bridge From Old to New in Christian Belief (London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1973), p. 105. These words correspond to, and indeed interpret the teaching of Jesus, when l i e said: "I give you a new commandment: love one another" (John 13:34). And to indicate that this love is not to be sectional or for fellow Christians alone, Jesus is quoted as saying in another context: Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven, for he causes his sun to rise on the bad as well as on the good, and sends down rain to fall on the upright and the wicked alike. For if you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Do not even the lax collectors do as much? (Ml. 5:44 - 46, Luke 6:27). The practical eschatological implication of love of God and neighbour is spelt out by Jesus when He is quoted as saying that what one does to one's neighbour will decide who gains access to heaven hereafter (Mt. 25:31-46). Thus, Jesus is very explicit on what constitutes the will of God, or what God requires from human beings who desire to earn His blessings here and hereafter. Teofilo Cabestrero quotes Edward Schillebeeckx as noting "love that has only the vertical dimension, toward God, without the dimension toward humanity, would be a pseudo-charity, a pseudo-religion."^ That seems to be an obvious interpretation of the Scripture which enjoins that human beings should "Love one another; for love is of God, and he who loves is born of God and knows God", while "he who does not love does not know God; for God is love" (1John 4:7-X). It would does appear clear that anyone who does not love or do good, or anyone who is uncharitable, stingy, merciless or wicked cannot find joy and peace with God, eschatologically speaking, whether one were talking of prophetic or apocalyptic eschalology as documented in the Bible. ____________________ 38 Edward Schillcheeckx, in an Interview with Teofilo Cabestrero, Faith: Conversations with Contemporary Theologians: Ladislaus Boros, Georges Casalis, Jose Comblin, Enrique D. Dussel, Segundo Galilea, Giulio Girardi, Jose Maria Gonzalez, Hans Kung, Jurgen Moltmann, Karl Rahner, Joseph Ratzinger, Edward Schillebeeckx, Juan Luis Segundo, Jean Marie Tillard (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1981), p.166 Eschatology in Critical Theological Discourse This sub-title is not to suggest that what has been done so far has not been critical. In this section, the locus is on what some liberal theologians have said about Christian eschatology. Richard P. McBrien notes that: The liberals hold that Jesus himself did not intend a Church because he expected the Kingdom of God as imminent: at first within his own lifetime, and then as something that would come about immediately after his death. The disciples, therefore, expected the Second Coming in the very near future. They perceived themselves as the ultimate Messianic Community of the Saints, the elect of the final generation who would soon enter a new form of being in the new aeon. With the further delay of the parousia, the post apostolic Church abandoned this Pauline view and assumed organizational form of a type that suggested some historical permanence. 39 The originators and holders of this view include, as McBrien notes, Johannes Weiss, Albert Schweitzer, Adolf HArnack, and Martin Werner.40 In consonance with that, Dermot A. Lane notes that the important work of Johanness Weiss, Jesus's Proclamation of the Kingdom of God, has triggered off the twentieth century interest in eschatology. As he notes, "Weiss argued that eschatology was at the very centre of first-century Christianity and that if we are to understand the gospel of Jesus we must come to grips with eschatology". Lane explains further that the "emphasis was taken up and continued by Albert Schweitzer". According to Lane: This biblical focus in turn was complemented by the many questions about the future of humanity arising out of the horrors of (wo world wars and the Jewish holocaust. Further, the sixties saw the development of different theologies of hope (J. Moltman, W. Pannenberg), and the seventies the emergence of political theology in Europe and liberation theology in Latin America. In addition, eschatology has been given a new urgency through the result of the real possibility of a nuclear destruction of the human race and the world.41 ___________________________ 39 Richard P. McBrien, ibid., p. 575. Ibid. 41 Dermot A. Lane, ibid., p. 337f 40 Of course, circumstances can encourage human beings to reflect on certain subjects at certain historical periods. McBrien presents a long l i s t of theologians and their viewpoints on eschatology. The list includes both Roman Catholic and Protestant theologians.42 In essence, they all uphold the centrality of eschatology to Christianity as encapsulated in the concept of the kingdom of God, as proclaimed and pursued by Jesus. Eschatology Today It has been stated from the very beginning, in the introductory section of this article that eschatology seems to be in eclipse in this age. The preoccupation here is to elaborate a little bit on that point, and to look into the causes, and their evaluation, toward a balanced state of being a Christian, eschatologically speaking. The talk about the eclipse of Christian eschatology may not appear to be as grave as it is to some theologians, but as far back as 1973, Seef Konijin, from Holland, noted that "most young people take a pretty skeptical line abut the whole thing."4 Vittorio Messori, an Italian, who wrote in 1985, was earlier quoted as making a similar observation about the apparent eclipse of Christian eschatological doctrine. Peter C. Phan, from the Catholic University of America, in his own work which dates 1997, explains that "the misuse and abuse of eschatology, combined with I he overly individualistic and otherworldly casting of this doctrine, were among the factors that eventually brought about the silence of many preachers about the afterlife." In oilier words, because Christian eschatology became extremely otherworldly, many contemporary Christians could not see the relevance of it to then daily lives. As Phan further notes, ______________________________ 42 Richard P. McBnen. Ibid., pp.1138-1154. Seel Konijn, ibid., p. 115. 44 Peter C. Phan, ibid., p. 17. 43 they were no longer moved by the stereotyped "fire-and-brimstone sermons." Along that line, there was also the ancient abuse of the Indulgence, in relation to the purgatory doctrine. Although, as Ratzinger notes, the concept of Indulgence "has lost a lot of meaning since it is not plausible in terms of today's thinking,"46 it must have contributed one way or the other to the decline of Christian eschatology. Moreover, one would think that the emergence of many Pentecostal churches that emphasise breakthrough miracles and prosperity gospel which stresses t h i s worldly success tends to obliterate seeking the heavenly kingdom of God, to an alarming extent. The general impression m one's perception is that many Pentecostals preach the faith in the light of realised eschatology. John F. Mat-Arthur. Jr., notes that: Virtually every false religion ever spawned by man worships a god whose function is to deliver some sort of cargo. That is, human religions invent gods for utilitarian reasons: the deities exist to serve men. rather than the other way around. World Faith theology has turned Christianity into a system no different from the lowest human religions - a form of voodoo where God can be coerced, cajoled, manipulated, controlled, and exploited for the Christian's own ends.' 47 The import of this quotation is that dubious Pentecostals, like every charlatan, can be misleading, and dangerous to Christian faith, including the eschatological aspect of the faith. It should be noted that hardly can one find a church that has not been affected by Pentecostalism, both in terms of seeking for miracles and in materialistic distraction. With particular reference to materialism, William E. McManus. the American retired Catholic Bishop of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Indiana, noted that: __________________________ 45 Ibid. 46 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, with Vittorio Messori, ibid., p. 147. 47 John F. MacArthur, Jr.. Charismatic Chaos: Signs and Wonders, Speaking in Tongues, Health, Wealth and Prosperity, Charismatic Televangelism, Does God Still Speak Today? (Michigan: OASIS International Ltd., 1992), p. 265 During most of this century, bishops and pastors were caught up in a building craze, and the laity readily joined in the fun. In selling budgets for new buildings, particularly for elaborate churches, the sky was the limit: but diocesan and Church employees, particularly the unskilled, were as poor as church mice and trapped into low-paying jobs with no possibility for advancement and no promise of an adequate pension.48 Although this observation was made as far back as 1986, the situation has not changed in the perception of this research. Sylvanus Okechukwu notes in 2004, for instance, how the Catholic Seat of Wisdom Seminary, Nigeria, has 93 employees, and most of them were paid salaries that could not meet their basic personal needs, not to talk of dependants. He said the same situation applied to diocesan and parish employees in Nigeria, generally speaking.49 In respect of West Africa as a whole, Moses Audi notes that: The communities of West Africa are becoming more and more corrupt. The religious people have no moral influence in the society because nothing makes them different. Religion has lost its ability to modify relationships, interests, manners and actions 50 In the same vein, Bernard Joinet notes generally that "modern society" is seen to be "godless, corrupt and promiscuous". ___________________ 48 William E. McManus, "Getting Our House in Order", in Dennis M. Corrado and James F. Hinchey (eds), Shepherds Speak: American Bishops Confront the Social and Moral Issues that Challenge Christians Today (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1978). p. 69. 49 Sylvanus Okechukwu, "Relevance of the Church to Human Rights and the Challenges of the Pastoral Ministry in A Pluralistic Society", in Maurice Jiwike, The Challenges of Pastoral Ministry in Pluralistic Society (Owerri: Assumpta Press, 2004), p. 28f. 50 Muses Audi, "An Overview of Contemporary Godliness in the Morality of West African Society", in Joshua N. Kudadjie, Rebecca Y. Ganusah, and Adekunle Alalade (eds). Religion, Morality and West African Society (Accra: West African Association of Theological Institutions, 2002), p. 109. 51 Bernard Joinet The Challenge of Modernity in Africa (Nairobi: Paulines Publication Africa, 2000), p.5 All of that seems to be too far afield from Christian eschatology, which can be summarized as seeking the kingdom of God here and hereafter. While the miracles of Jesus indicate that God is not opposed to earthly well-being. He is quoted as asserting that nothing can be more treasured than entrance into the heavenly kingdom of God (Mat. 13:44-45; Mark S:36 37). Lucien Richard quotes Jurgen Moltmann as aptly stating that "each of us has waiting for us in our lives a measure of suffering which we are called upon to assume in solidarity with all who suffer."" Within the context of this study, the implication is that faith in miracle cannot remove all the burden of the cross from I he life of a Christian, just as indicated by Jesus (Mat. 10.38). And that constitutes a challenge for faithful Christians, to embrace their crosses, and follow His footsteps. At the same time, as Richard further notes in an eschatological reference to J. B. Metz's Faith in History and Society. it should be emphasized that "all social institution and transformation are provisional and cannot be identified with the kingdom of God." It would seem, of course, that "the kingdom of God" in that quotation refers to heaven, rather than the aspiration to build the kingdom of God on earth. Because the latter is transitory, though desirable. Jesus plausibly enjoins that Christians should not forget to keep treasure in heaven, where there is absolute security (Mat. 6:19 - 20). In practical terms, there seems to be no other way of storing treasure in heaven, as Jesus enjoins, than through generosity, merciful and compassionate acts. That is clearly stated in the three synoptic Gospel accounts (Mat. 19:21; Mark 10:21, and Luke 18:22). Conclusion This eschatological review has featured a fairly elaborate definition of the term, "eschatology", due to the diversity that characterizes ___________________________ 52 Lucien Richard, What Are They Saying About the Theology of Suffering (New York: Paulist Press. 1992), D. 52. 53 Ibid. p. 70. its conception. Basically, it is discovered that the two forms of eschatology, prophetic and apocalyptic, that are found in the O.T. a r e the same w i t h the eschatological ideas that are contained in the teaching of Jesus. While prophetic eschatology emphasizes earthly well-being, based on justice, mercy and generosity, as indispensable conditions for earning God's favour, apocalyptic eschatology stresses the notion of reward hereafter for positive heroic faith and action fulfilled while on earth. The study establishes the concern that eschatology has hugely diminished in contemporary Christianity, despite its being acknowledged by many eminent theologians as the key to comprehending the life and mission of Jesus. Many prominent theological scholars hold that no one can claim to know Jesus, without viewing Him with an appropriate eschatological lens. The decline of Christian eschatology is said to anchor on the general decline of religion, with particular reference to its ability to influence good behaviour and action. The religious set-back in turn is said to feed on widespread materialism and financial fraud, globally speaking. It is a common observation, among many Christian scholars, that there is a predominant over-preoccupation with miracles and earthly desires, which leave little or no room for generosity, mercy, compassionate acts, and humanitarian sacrifice, as enjoined by Jesus, with special reference to the idea of the cross, inward eschatological benefits.