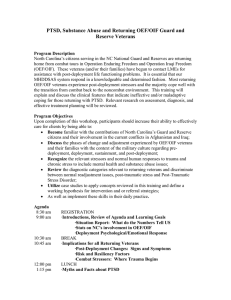

RETURNING FROM THE SUCK DIAGNOSED WITH PTSD AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

advertisement