Contracts – Haley, Fall 2005

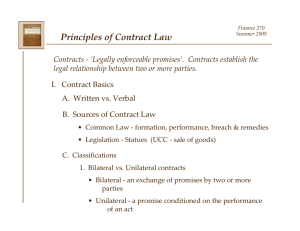

advertisement