CHAPTER 18 THE INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY A MACHINE CULTURE

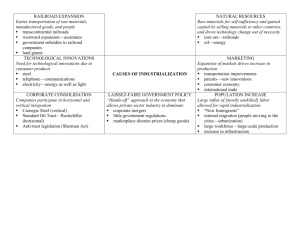

advertisement

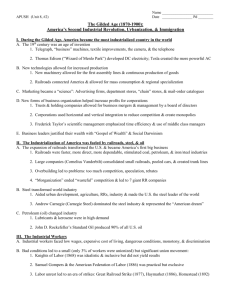

CHAPTER 18 THE INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY A MACHINE CULTURE The author uses the Grand Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 to make the point that while the American people could look back on a century of national history of which they were proud, they were more interested in looking toward a future in which they would be a powerful industrial giant. . INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT The United States offered ideal conditions for rapid industrial growth at the end of the nineteenth century. There was an abundance of cheap natural resources, large pools of labor, the largest domestic market in the world, and capital and government support without government regulation. Industrial development was not always smooth and the North and East tended to reap most of the rewards, but between 1865 and 1914 the rate of growth continued to be very rapid. AN EMPIRE ON RAILS The industrial economy of nineteenth-century America was based on the expansion of the railroads, which consumed great quantities of raw materials, employed thousands of people, and necessitated new forms of business organization. A. Building the Empire Between 1865 and 1916, the United States laid down over two hundred thousand miles of track at a cost in the billions of dollars. A great deal of the expense was met by local and state governments and, especially in the West, by the federal government. Even with all the fraud and waste connected with government grants, the railroads saved the federal government about one billion dollars between 1850 and 1945. B. “Emblem of Motion and Power” The railroads did more than supplement other forms of transportation. They ended rural isolation, allowed regional economic specialization, made possible mass production and consumption, led to the organization of the modern business corporation, and stimulated other industries. The railroads also captured the imagination of the American people. C. Linking the Nation Via Trunk Lines At first, railroads were built by and for local interests. At the time of the Civil War, the nation did not have an integrated rail system. During and after the war, construction and consolidation of trunk lines proceeded rapidly under the direction of men such as Cornelius Vanderbilt. The eastern seaboard was directly linked with the Great Lakes and the West. The southern railroad system grew at an exceptional rate in the 1880s and was integrated into the national network. At the same time, rail transportation was becoming safer, speedier, and more reliable. D. Rails Across the Continent Congress voted to build a transcontinental railroad in 1862 and allowed two companies to compete in its construction. The Union Pacific worked westward from Nebraska, using Irish laborers. The Central Pacific worked eastward, using Chinese immigrants. It became a race, each company vying for land, loans, and potential markets. On May 10, 1869, in Utah, the tracks met. By 1900, four more lines reached the Pacific. E. Problems of Growth If anything, too much track was put down in the United States. Competition between railroads became intense, and all efforts by railroadmen to share freight in an orderly way failed. After the Panic of 1893, bankers like J. P. Morgan gained control of the railroad corporations. Opposing “wasteful” competition while favoring efficiency and combination, the bankers imposed order. In 1900, nearly all freight was carried by seven giant railroad systems. AN INDUSTRIAL EMPIRE The Bessemer process of refining steel made mass production possible and the use of steel caused great changes in manufacturing, agriculture, transportation, and architecture. A. Carnegie and Steel Large-scale steel production required access to iron ore deposits in Minnesota and extensive transportation networks. Because of the massive amounts of capital required to enter steel production, there were never very many major steel companies. Nevertheless, competition was keen for awhile and led to vertical integration of the industry. In 1872, Andrew Carnegie entered the steel business and became its master. His company produced the steel for the Brooklyn Bridge and the Washington Monument, and for the growing cities. By 1901, Carnegie employed more than twenty thousand people and produced more steel than Great Britain. In that year he sold out to J. P. Morgan, who headed a group that incorporated the United States Steel Company, the nation’s first billion-dollar corporation. B. Rockefeller and Oil Long before Americans drove cars, oil became a big business; the most profitable use of petroleum was in the form of kerosene for lighting. The first oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania in 1859, and its success led to intense competition. In 1863, John D. Rockefeller began to consolidate the oil business when he organized the Standard Oil Company of Ohio. By meticulous attention to the smallest detail, Rockefeller lowered costs and improved quality. Standard Oil was also remarkably successful in establishing an efficient marketing operation. As his business spread beyond Ohio, Rockefeller maintained centralized control by creating a holding company, called the Standard Oil Trust, that owned and managed member companies. This managerial innovation was copied by other large companies, and the word “trust” became synonymous with “monopoly.” C. The Business of Invention American technology is the child of the latter part of the nineteenth century. Gifted individuals Thomas Edison for example, or teams working in research laboratories turned out a succession of inventions, the telegraph, the camera, processed foods, the telephone, the phonograph, the incandescent lamp, that made life easier. Electricity lit homes and factories and powered urban transportation systems. THE SELLERS Marketing became a science in the late nineteenth century. Advertising became common, and new ways of selling products, such as the department store, chain store, use of a brand name, and mail-order catalogs, became popular. Americans became a community of consumers, a community that to some degree overcame ethnic and economic differences. THE WAGE EARNERS The American labor force, in general, benefitted from a rise in real wages in the last quarter of the century. A. Working Men, Working Women, Working Children The labor force was composed of many different people: skilled and unskilled, men and women, adults and children, native-born and immigrants, Protestants and Catholics, whites and blacks. Nearly always it was the skilled, white males who received a greater share of America’s increasing prosperity. Still, for all workers, the work week was a long one. B. Culture of Work It was difficult for immigrants and rural folk to adjust to the new work habits imposed by the factory, but most adjusted to the new conditions and many even advanced themselves or saw their children go on to better jobs. C. Labor Unions Early labor unions, such as the Knights of Labor, were more like fraternal orders than unions as we know them. The Knights, for example, opposed strikes and refused to accept the fact that many workers would never become their own bosses. The first modern union was founded in 1881 by Samuel Gompers. The American Federation of Labor recognized that the industrial system was permanent and concentrated on practical steps to improve wages and working conditions. The American Federation of Labor, however, organized only skilled workers while ignoring women and African Americans. D. Labor Unrest Employers and employees responded to different imperatives, and often came into violent conflict. Employees tried to humanize the factory by working according to habitual, natural rhythms, while employers tried to apply the strict laws of the market. The result was an era of strikes. In 1877 the rail system was practically shut down, and from 1880 to 1900 there were 23,000 strikes. Many of them turned violent. The worst incident took place in Chicago in 1886. In this Haymarket “incident” some policemen were killed, and fears of an anarchist uprising spread. CONCLUSION: INDUSTRIALIZATION’S BENEFITS AND COSTS Despite the unquestionable benefits of rapid industrialization, in terms of national power and wealth and even in terms of an improving standard of living, many Americans questioned whether these benefits were worth the exploitation, the social unrest, the growing disparity between rich and poor, and the increasing power of the giant corporations.