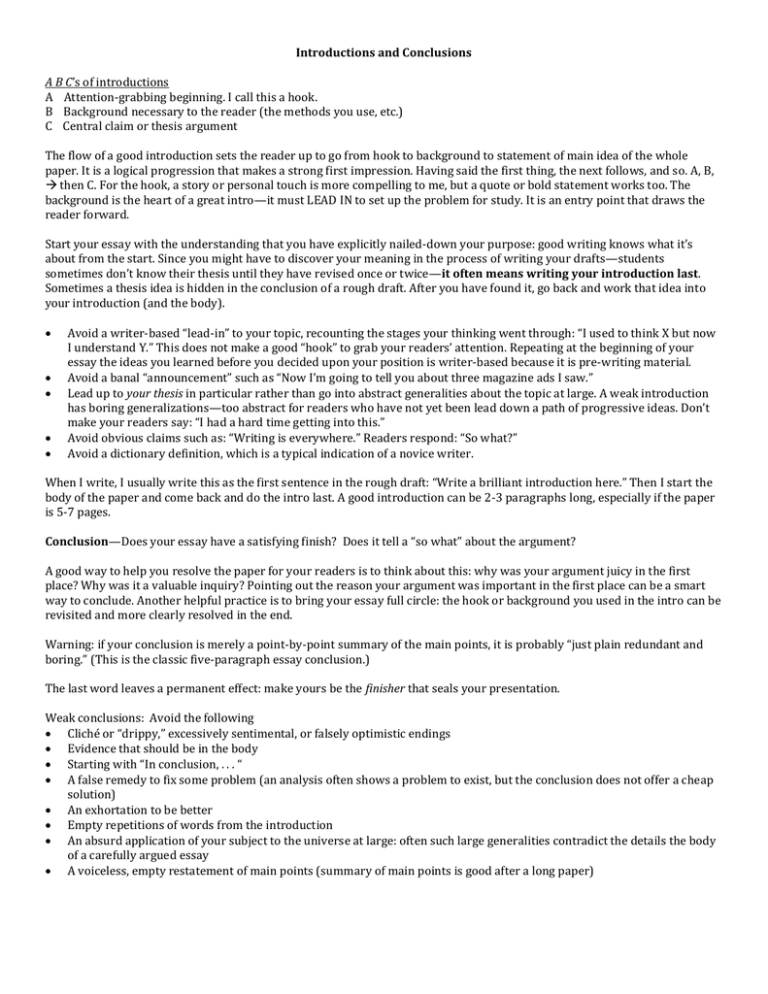

Introductions and Conclusions

advertisement

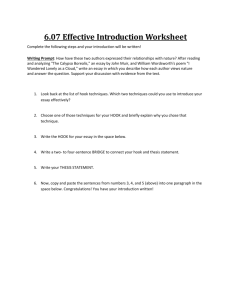

Introductions and Conclusions A B C’s of introductions A Attention-grabbing beginning. I call this a hook. B Background necessary to the reader (the methods you use, etc.) C Central claim or thesis argument The flow of a good introduction sets the reader up to go from hook to background to statement of main idea of the whole paper. It is a logical progression that makes a strong first impression. Having said the first thing, the next follows, and so. A, B, then C. For the hook, a story or personal touch is more compelling to me, but a quote or bold statement works too. The background is the heart of a great intro—it must LEAD IN to set up the problem for study. It is an entry point that draws the reader forward. Start your essay with the understanding that you have explicitly nailed-down your purpose: good writing knows what it’s about from the start. Since you might have to discover your meaning in the process of writing your drafts—students sometimes don’t know their thesis until they have revised once or twice—it often means writing your introduction last. Sometimes a thesis idea is hidden in the conclusion of a rough draft. After you have found it, go back and work that idea into your introduction (and the body). Avoid a writer-based “lead-in” to your topic, recounting the stages your thinking went through: “I used to think X but now I understand Y.” This does not make a good “hook” to grab your readers’ attention. Repeating at the beginning of your essay the ideas you learned before you decided upon your position is writer-based because it is pre-writing material. Avoid a banal “announcement” such as “Now I’m going to tell you about three magazine ads I saw.” Lead up to your thesis in particular rather than go into abstract generalities about the topic at large. A weak introduction has boring generalizations—too abstract for readers who have not yet been lead down a path of progressive ideas. Don’t make your readers say: “I had a hard time getting into this.” Avoid obvious claims such as: “Writing is everywhere.” Readers respond: “So what?” Avoid a dictionary definition, which is a typical indication of a novice writer. When I write, I usually write this as the first sentence in the rough draft: “Write a brilliant introduction here.” Then I start the body of the paper and come back and do the intro last. A good introduction can be 2-3 paragraphs long, especially if the paper is 5-7 pages. Conclusion—Does your essay have a satisfying finish? Does it tell a “so what” about the argument? A good way to help you resolve the paper for your readers is to think about this: why was your argument juicy in the first place? Why was it a valuable inquiry? Pointing out the reason your argument was important in the first place can be a smart way to conclude. Another helpful practice is to bring your essay full circle: the hook or background you used in the intro can be revisited and more clearly resolved in the end. Warning: if your conclusion is merely a point-by-point summary of the main points, it is probably “just plain redundant and boring.” (This is the classic five-paragraph essay conclusion.) The last word leaves a permanent effect: make yours be the finisher that seals your presentation. Weak conclusions: Avoid the following Cliché or “drippy,” excessively sentimental, or falsely optimistic endings Evidence that should be in the body Starting with “In conclusion, . . . “ A false remedy to fix some problem (an analysis often shows a problem to exist, but the conclusion does not offer a cheap solution) An exhortation to be better Empty repetitions of words from the introduction An absurd application of your subject to the universe at large: often such large generalities contradict the details the body of a carefully argued essay A voiceless, empty restatement of main points (summary of main points is good after a long paper)