Care of the Down Syndrome Patient for the Primary Care Physician

advertisement

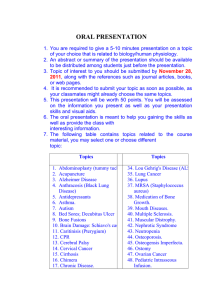

Care of the Down Syndrome Patient for the Primary Care Physician Jennifer Gibson, M.D. Assistant Professor, ETSU Pediatrics SW VA Pediatrics Conference, August 3, 2013 Disclosure Statement I DO NOT have a financial interest/arrangement or affiliation with one or more organizations that could be perceived as a real or apparent conflict of interest in the context of the subject of this presentation. I DO NOT anticipate discussing the unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device during this activity or presentation. Overview Down Syndrome: History, Epidemiology, & Genetics Down Syndrome Physical Features Diagnosis—How to Diagnose Prenatally and How to Break the News Effect of Down Syndrome on the Family Review of Systems—What Can Go Wrong AAP Health Maintenance Recommendations References and Image Sources Down Syndrome: History, Epidemiology, & Genetics History of Down Syndrome Initially described in 1856 by John Langdon Down, an English physician Described people with distinctive physical features & decreased intellectual ability as grouped into one syndrome Used the term “mongoloid” because the facial features of these patients were similar to those of the Mongolian people Syndrome linked to a chromosomal abnormality in 1959 by Dr. Jerome Lejeune, a French physician Discovered that “mongoloids” had 47 chromosomes whereas people without the syndrome had 46 chromosomes Shortly thereafter, he performed a karyotype showing Trisomy 21 Image of Dr. Down from DownSyndrome.com, image of Dr. Lejeune from Wikipedia.org Down Syndrome Demographics Most common chromosomal malformation in newborns Incidence is usually described as ~1 in 700 livebirths Average life expectancy is 49 years (as of 1997) Increased from 25 years in 1983 Most common causes of death are congenital heart disease and respiratory infections Classically has been associated with advanced maternal age Improved life expectancy due to early surgical repair of heart defects and anomalies of GI tract Total population of individuals with Down Syndrome is growing and will continue to grow! Down Syndrome Demographics There is no national registry for prenatal diagnoses of Down Syndrome or number of livebirths per year. Review of the National Center for Health Statistics data on Down Syndrome from 1989-2006: Overall, there has been an 11% decrease in Down Syndrome births from 1989-2006; however, there was a major decline from 1989-1997 with increasing numbers from 1997-2006 Most Down Syndrome deliveries occur to mothers ages 15-34 years (also population with greatest number of deliveries) Highest number of Down Syndrome births occur in the South; fewest births occur in the Northeast Non-Hispanic whites deliver the most infants with Down Syndome; African-Americans deliver the fewest Number of births is fairly equal regardless of educational level Down Syndrome Genetics Sporadic Trisomy 21 95% of diagnoses Non-familial 47 chromosomes (one extra chromosome 21) Image from Zitelli Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis Down Syndrome Genetics Unbalanced Translocation 3-4% of diagnoses Excess chromosome 21 material attached to another acrocentric chromosome, usually chromosome 14 ¾ are new mutations but must rule out a balanced translocation in the parents Mosaicism 1-2% of diagnoses Mix of 2 cells lines—one with Trisomy 21, one normal Image from Zitelli Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis Down Syndrome Phenotype Physical Findings in Down Syndrome Facial Small ears Upward slant of eyes Epicanthal folds Brushfield spots Flattened nasal bridge Small mouth Protruding tongue Brachycephaly Neck and Chest Nuchal skin fold Small internipple distance Images from Zitelli Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis Physical Findings in Down Syndrome Extremities Single transverse palmar crease Clinodactyly of fifth digit Wide space between 1st and 2nd toes Neurologic Hypotonia Extremity Images from Zitelli Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis; Hypotonia Image from Living With Cerebral Palsy Website Prenatal Diagnosis Prenatal Diagnosis Earliest screening methods—maternal age and/or history of previous infant with Down Syndrome Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling both provide a means to screen but present a small chance of pregnancy loss—not ideal! Multiple screening methods in use today as well as various combinations of screens American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends offering all pregnant women in the US prenatal screening and diagnosis of Down Syndrome Prenatal Diagnosis Techniques Fetal nuchal translucency Done via ultrasound at 11-14 weeks’ gestation Review of 34 studies revealed 76.8% sensitivity in detecting Down syndrome with false positive rate 4.7% Results dependent on sonographer experience Rosen T, D’Alton M. Down syndrome screening in the first and second trimesters: What do the data show? Seminars in Perinatology. 2005:29:367-375. Prenatal Diagnosis Techniques Second Trimester Screen Triple Screen—serum test for decreased maternal alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), decreased human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and decreased estriol (E3) Quadruple Screen—Triple Screen plus serum test for elevated maternal inhibin-A Detection rate of 60% with false-positive rate of 4% Detection rate of 67-76% with false-positive rate of 5% First Trimester Screen Serum test for decreased pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) and elevated free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) Detection rate of 60-74% with false-positive rate of 5% How to Tell the Family How to Break the News 2009 Pediatrics review of 19 articles addressing the best way to deliver a post-natal diagnosis Total of 3359 parental responses evaluated Parents prefer to hear the news from the obstetrician and the pediatrician together and to be informed as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Parents prefer to have the discussion in a private place, to be together, and to have the infant present. Parents prefer that the conversation begin with positive words and that language conveying pity, personal tragedy, or extreme sorrow be avoided. How to Break the News In the initial conversation, parents want 3 questions answered: What is Down Syndrome? What causes Down Syndrome? What does it mean to live with Down Syndrome? In the initial conversation, parents prefer to discuss only those complicating medical conditions which the infant is suspected of having or developing in the first year. Parents want contact information for local support groups and community resources as well as a list of information resources (National Down Syndrome Society). How Does Down Syndrome Affect the Patient’s Family? Down Syndrome Disease Burden and Family Impact 2011 study examined the results of the 2005-2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs to profile the families of children with Down Syndrome Telephone survey conducted by the CDC Survey of parents who reported a child with “Special Health Care Needs” (SHCN)—Down syndrome, asthma, ADHD, autism, cardiovascular, epilepsy, CP, cystic fibrosis, etc. Questions included use of a medical home, presence of unmet needs for care, lack of family support services Found that 70% of parents of Down syndrome children reported having no medical home; parents were 2x as likely to report unmet needs and lack of support than parents of children with other SHCN Review Of Systems Cognitive Effects All patients have some degree of cognitive impairment. Mental development decelerates between 6 months and 2 years of life with a persistent plateau during adolescence Most patients will have mild or moderate cognitive impairment; severe impairment is rare Language production is often very impaired Mild—IQ 50-70 Moderate—IQ 35-50 Severe—IQ 20-35 Also with delayed verbal short-term memory Early intervention education systems can be initiated within the first months of life and help to stimulate development—goal is adult social independence Cardiovascular Most common structural defects in Down Syndrome Prevalence of congenital heart defects in Down Syndrome neonates is 44-58% worldwide Atrioventricular septal defects (aka endocardial cushion defects) & VSDs are the most common Other defects: ASD, PDA, & Tetralogy of Fallot Higher incidence of persistent pulmonary hypertension If Down Syndrome was diagnosed prenatally, fetal echocardiogram may detect some defects Atrioventricular Septal Defect Diagram from MyKentuckyHeart.com Website Cardiovascular Physical examination poorly predicts the presence of congenital heart defects in Down Syndrome infants Echocardiography is recommended for ALL patients with Down Syndrome within the first month of life Goal of early detection is to prevent complications where possible (i.e. congestive heart failure with left-to-right shunting, cyanosis in ToF) Surgical repair of significant defects is usually done at 2-4 months if possible Gastrointestinal 2nd most common structural defect after cardiac Duodenal Atresia and/or Stenosis Most common GI structural defect in Down Syndrome Incidence rates 1-5% Presents as bilious vomiting on DOL#1 Appears as “double-bubble” on abdominal x-ray Requires nasogastric decompression and surgical correction Image from Zitelli Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis Gastrointestinal Hirschsprung Disease Found in 1-3% of Down Syndrome infants More frequent in males Symptoms include delayed passage of meconium, chronic constipation, failure to thrive May see transition zone on barium enema; diagnosed with suction rectal biopsy Requires surgical correction (may include temporary colostomy) X-ray image from VCU’s Pedsradiology.com Website; Surgical image from Zitelli Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis Gastrointestinal Other structural defects: Celiac Disease Seen in 5-7% of children with Down Syndrome (10x higher than the prevalence rate in the general population) Can monitor with IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies beginning at age 3 years Gastroesophageal reflux anal atresia/stenosis esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula Rule out aspiration in recurrent lung infections Constipation Serious problem resulting from hypotonia Ophthalmologic More than half of patients with Down Syndrome will have an occular abnormality Brushfield spots Congenital cataracts White-brown spots in the periphery of the iris Produced by collections of connective tissue Seen in 38-85% of children with Down Syndrome Seen in 4-7% of Down Syndrome infants (10-fold higher prevalence than the general population) Refractive Errors Seen in 43-70% of children with Down Syndrome Examination is usually difficult Does not improve as the child ages Ophthalmologic Strabismus Misalignment of the eyes If uncorrected, can result in loss of vision Treat with occlusion, correction of refractive error, surgery Seen in 20-45% of children with Down Syndrome Nystagmus Fine, rapid horizontal nystagmus Occurs in 15-30% of children with Down Syndrome Does not require intervention Image from Reecesrainbow Website Otolaryngology Stenotic external ear canals Seen in 40-50% of infants with Down Syndrome Often result in cerumen impaction and limited visibility Likely will require visualization by ENT specialist Canals should grow as the child ages; by age 3-4 years, no special equipment is required for cerumen removal or for tympanic membrane visualization Chronic otitis media Increased risk for many reasons (increased frequency of URI, midface hypoplasia with abnormal eustachian tube insertion, hypotonia of palatal muscles create negative pressure) Will take longer to resolve than in unaffected children May require multiple sets of PE tubes Otolaryngology Hearing loss Historically, ~75% of patients with Down Syndrome developed some hearing loss Most hearing loss is conductive, but sensorineural and mixed type hearing losses are also seen ABR hearing screens should be done in Down Syndrome patients, as OAE is inaccurate if middle ear fluid is present Puretone audiometry can detect differences between ears; however, only 40% of 4-year-olds with Down Syndrome can cooperate to accurate perform the testing Even mild hearing loss should be corrected to maximize the patient’s potential for language and education Otolaryngology Chronic rhinorrhea/sinusitis Due to midface hypoplasia and small respiratory passages Abnormal development of the frontal, maxillary, and sphenoid sinuses Usually will resolve with growth Consider testing immunoglobulin levels, referral for allergy testing, avoidance of environmental smoke Utilize nasal saline rinses, nasal steroids, oral antihistamines May need adenoidectomy; if already performed, consider imaging with CT to look for re-growth of adenoid tissue Otolaryngology Obstructive Sleep Apnea Predisposing factors—midface hypoplasia, large adenoids and tongue, small respiratory passages, obesity Contributes to failure to thrive and pulmonary hypertension; poor sleep also worsens neurodevelopment and behavior Seen in over 60% of patients with Down Syndrome Evaluate with thorough history and physical exam, formal sleep study in a sleep lab Consider treatment with nasal saline washes, CPAP (may not be well-tolerated), T&A (effective in only 50%) Dental Abnormalities Down Syndrome patients may demonstrate delayed dental eruption or eruption out of sequence Dental anomalies are 5x more common in Down Syndrome patients Teeth are often malformed (sharp, pegshaped), small, and malaligned Congenital absence of teeth (particularly the lateral incisors) is also seen Roots are conical which leads to an increased risk for periodontal disease Increased risk for dental caries—poor oral hygiene, decreased immune response to oral pathogens Image from IntellectualDisability.info Respiratory Respiratory infections are responsible for the majority of the morbidity and hospital admissions in patients with Down Syndrome Down Syndrome is an independent risk factor for developing bronchiolitis with RSV infection Pneumonia commonly precedes admission to the PICU Increased risk for hospitalization and for prolonged stay Higher incidence of acute lung injury than the general population Increased risk of progression to ARDS Higher risk for difficult intubation and subglottic stenosis Recurrent wheeze is very common (up to 36%) Other anomalies—tracheolaryngomalacia, pulmonary hypoplasia Immunology Increased susceptibility to infections is linked to abnormal immune system parameters Down Syndrome is the most common recognizable genetic syndrome associated with immune effects Adaptive Immunity: Innate Immunity Decreased T cell and B cell counts Lack of normal early T cell expansion of infancy Smaller thymus Decreased IgA in saliva Decreased antibody response to immunizations Decreased chemotaxis of neutrophils Allergies are not highly-prevalent in Down Syndrome children (despite chronic rhinorrhea) Endocrinology Thyroid Abnormalities Reported in 28-40% of children with Down Syndrome with increasing frequency as children age Congenital hypothyroidism—2-3% Autoimmune (Hashimoto) thyroiditis—1% Compensated hypothyroidism—25-33% (isolated elevated TSH) Graves’ Disease—0-2% Diabetes Mellitus—1% of children with Down Syndrome Musculoskeletal Most problems are due to ligamentous laxity Occipitoatlantal Hypermobility Seen in up to 60% of patients with Down Syndrome Lower risk of neurologic compromise Atlantoaxial Instability Seen in 15-40% of patients with Down Syndrome (most frequently-occurring orthopedic problem) Occurs due to laxity of the transverse ligaments and can develop during periods of growth Defined as a distance of >4.5 mm from the odontoid process of the axis to the anterior arch of the atlas Usually 12-15% of patients with instability will go on to develop neurologic sequelae from spinal cord compression Consider fusion of vertebrae if distance is >10 mm and neurologic compromise if felt to be imminent Atlantoaxial Instability/Subluxation Diagram of vertebrae from Atlas of Chiropractic, Rehabilitation, and Massage Therapy Website, Diagram of instability from Judo and Down Syndrome Website; X-ray from Learning Radiology.com Atlantoaxial Instability Basic guidance: Obtain lateral neck x-rays in neutral, flexion, & extension positions at 3-5 years & later if symptoms present If instability is present, avoid tumbling/diving/football Obtain films prior to any operations or therapies which involve neck positioning Review symptoms of cord compression with the family Musculoskeletal Aquired Hip Instability Seen in 5% of patients with Down Syndrome Usually presents at 2-3 years of age Progresses from acute to chronic to fixed dislocations May be painful Likely will require surgical correction Patellofemoral Dislocation Occurs in 4-8% of Down Syndrome patients Often presents around 2-3 years of age Usually well-tolerated but may produce some pain Conservative management with patellar sleeves, medication, and activity restriction Surgery may become necessary to preserve ambulation Musculoskeletal Foot Abnormalities Include pes plano-valgus, metatarsus primus varus, and bunions Usually well-tolerated and treated with supportive shoes Diagram of dislocation from UMMC website, image of pes plano-valgus from Medical Observer website Hematology/Oncology Transient neonatal neutropenia and thrombocytopenia with increased nucleated red cells (no increased blasts!) Transient Abnormal Myelopoiesis (TAM) aka Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder,Transient Leukemia Seen in 10% of babies with Down Syndrome Potential to transform into Myeloid Leukemia of Down Syndrome (ML-DS) Presents in fetal or neonatal period Fetal period—hydrops or anemia; worse prognosis Neonatal—circulating blasts with/without leukocytosis, bruising, exudative effusions, respiratory distress, hepatomegaly Labs: normal hemoglobin and neutrophil count with thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis, nucleated RBCs, immature blasts Usually resolves within 3 months spontaneously; symptomatic patients may be treated with low-dose cytosine arabinoside Hematology/Oncology Myeloid Leukemia of Down Syndrome Usually presents between 1 and 4 years of age 20-30% of cases developed either as a progression from TAM or after an apparent remission 70% of cases have preceding myelodysplastic phase— progressive anemia and thrombocytopenia with dysplastic changes to the erythroid cells and megakaryocytes as well as hypercellularity of the marrow Labs: reduced number of normal cells with dysplastic changes in all myeloid lines and circulating blasts Treatment with cytarabine 5-year survival rate of 80% Hematology/Oncology Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia of Down Syndrome 1.7x more frequent than ML-DS Clinical features are similar to ALL patients without Down Syndrome >90% have pre-cursor B-cell immunophenotype More likely to have a less favorable prognostic karyotype 60-70% of children are cured (less than cure rates for ALL without Down Syndrome) because of increased treatmentrelated toxicity events (infection and mucositis) Do not want to alter treatment because of high relapse rates Genitourinary Abnormalities Urinary Tract Abnormalities Seen in ~3% of children with Down Syndrome Hydronephrosis, hydroureter, renal agenesis, hypospadius No recommendations for routine screening with renal ultrasound, but clinical threshold to perform test is low Sexual Development Similar to other adolescents for both females and males Males have decreased ability to reproduce Education to prevent pregnancy Be aware of increased risk for sexual abuse in females Neurology Epilepsy—more common in Down Syndrome patients (0-13%) than in the general population Two age peaks—one in the infant period (40%), one in the 3rd decade (40%) Infant type—most likely infantile spasms or tonic-clonic seizures with myoclonus Onset at 6-8 months of age Male predominance; prematurity, congenital heart disease, and family history of epilepsy increase the risk Three EEG features: symmetrical hypsarrhythmia, no focus revealed with IV diazepam administration, single rather than clustered spasms on ictal EEG Difficult to treat—no true drug of choice (ACTH, vigabatrin, sodium valproate, phenytoin, diazepam) Probable worsening of neurodevelopmental outcome Early-onset adulthood—usually GTC or complex partial Behavior Very pronounced neurobehavioral and psychiatric problems—18-38% of Down Syndrome patients Most frequent in childhood are the “disruptive behavioral disorders” ADHD—6% Conduct Disorder/Oppositional Defiant Disorder—5% Aggressive Behavior—6.5% Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Autism Spectrum Disorder—6% More difficult to diagnose and to treat Difficult diagnosis—overlap in behaviors Psychiatric Disorders (more common in adults) Major Depressive Disorder—6% Growth and Nutrition Children with Down Syndrome tend to grow more slowly than children without the syndrome Special Down Syndrome growth curves were created to help account for this decreased growth rate (congenital heart disease, thyroid disorders, hypothalamic dysfunction, nutritional deficiencies, etc) Growth curves are more than 25 years old Current recommendation from AAP is to plot Down Syndrome children on the regular WHO/CDC growth curves Currently, CHOP is working on the production of new growth curves for Down Syndrome patients Growth and Nutrition Obesity Up to 50% of children with Down Syndrome can be classified as obese (higher than general population) Also at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes Multiple factors: Physiology—slowed metabolic rate (burn fewer calories), increased rates of hypothyroidism (slows metabolic rate), increased leptin (stimulates satiety, too much = decreased sensitivity), poor mastication (choice of softer foods) Behavior—less vigorous physical activity, ADHD, oppositional Management—encourage (safe) physical activity—family events, Special Olympics involvement Growth and Nutrition Nutrition Balanced diet with vitamin and mineral supplementation Caloric restriction to prevent obesity or promote weight loss Limits on portion sizes, reducing foods with hidden sugar (cereals, beverages) Encourage consumption of healthy softer foods (yogurts, steamed vegetables, purees) if chewing difficulties Discourage use of food as rewards or punishments Referral to nutritionist if necessary AAP Health Supervision Recommendations (2011) At All Health Supervision Visits (regardless of age) Monitor growth (height, weight, BMI) on standard WHO growth curves Evaluate for signs of neurologic compromise secondary to atlantoaxial instability Screen hearing every 6 months until normal hearing levels are established with ear-specific testing, then screen yearly Evaluate for symptoms of celiac disease Evaluate for evidence of seizures Evaluate for symptoms of sleep apnea Evaluate for behavioral issues Immunize appropriately, including 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine or Synagis as applicable Screening Labs and Referrals Echocardiogram at birth TSH at birth, 6 months, 12 months, and then annually CBC at birth; hemoglobin at 12 months and then annually with reticulocyte count and ferritin levels added if iron deficiency is a concern Ophthalmology referral prior to 6 months; follow-up yearly from 1-5 years, every 2 years from 5-13 years, and every 3 years from 13-21 years Sleep study referral prior to 4 years Neutral-position neck x-rays if neurologic signs present with flexion/extension x-rays only if neutral x-rays show no significant findings Anticipatory Guidance Discuss avoidance of excessive extension or flexion of the neck, contact sports and trampolines, and the need for asymptomatic patients to have x-rays prior to sports or Special Olympic participation Encourage optimal nutrition and exercise for the family Discuss available resources such as Early Intervention programs, in-school therapy services or education programs for vocational training, and local support groups; provide literature or websites for more information Prior to adolescence, discuss pubertal changes and need for female gynecological care Help with transition to adult medical care when appropriate References Arya R, Kabra M, Gulati S. Epilepsy in children with Down Syndrome. Epileptic Disorders 2011;13:1-7. Barksdale E. 2007. Surgery. In B Zitelli, H Davis (Eds) Atlas of Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia:Mosby, p 637-639. Bay C, Steele M, Davis H. 2007. Genetic Disorders and Dysmorphic Conditions. In B Zitelli, H Davis (Eds) Atlas of Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia:Mosby, p 9-10. Bull, M and Committee on Genetics. Clinical Report—Health supervision for children with Down Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2011;128:393-406. De Moraes M, de Moraes L, Dotto G, Dotto P, dos Santos L. Dental anomalies in patients with Down Syndrome. Brazilian Dental Journal 2007;18. Accessed online. Egan J, Smith K, Timms D, Bolnick J, Campbell W, Benn P. Demographic difference in Down syndrome livebirths in the US from 1989 to 2006. Prenatal Diagosis. 2011;31:389-394. Freeman S, Torfs C, Romitti P, Royle M, Druschel C, Hobbs C, Sherman S. Congenital gastrointestinal defects in Down Syndrome: A report from the Atlanta and National Down Syndrome Projects. Clinical Genetics. 2009;75:180-184. Haslam R. 2007. Spinal Cord Disorders. In R Kleigman, H Jenson, R Behrman, B Stanton (Eds) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed. Philadelphia:Sauders, p 2529. Jilg J. History of Down Syndrome. 2011. Published at DownSyndrome.com References McElhinney D, Straka M, Goldmuntz E, Zackai E. Correlation between abnormal cardiac physical examination and echocardiographic findings in neonates with Down Syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002;113:238-241. McGrath R, Stransky M, Cooley W, Moeschler J. National profile of children with Down Syndrome: Disease burden, access to care, and family impact. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;159:535-540. Murray J, Ryan-Krause P. Obesity in children with Down Syndrome: Background and recommendations for management. Pediatric Nursing. 2010;36:314-320. Murray J, Ryan-Krause P. Obesity in children with Down Syndrome: Background and recommendations for management. Pediatric Nursing. 2010;36:314-320. Ram G, Chinen J. Infections and immunodeficiency in Down Syndrome. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2011;164:9-16. Rosen T, D’Alton M. Down syndrome screening in the first and second trimesters: What do the data show? Seminars in Perinatology. 2005;29:367-375. Shott SR. Down syndrome: Common otolaryngologic manifestations. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 2006;142C:131–140. Skotko B, Capone G, Kishnani P. Postnatal diagnosis of Down Syndrome: Synthesis of the evidence on how best to deliver the news. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e751-758. Spiegel D, Hosalkar H, Dormans J, Drommond D. Cervical Anomalies and Instabilities. In In R Kleigman, H Jenson, R Behrman, B Stanton (Eds) Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed. Philadelphia:Sauders, p 2823-2826. References Stephen E, Dickson J, Kindley A, Scott C, Charleton P. Surveillance of vision and ocular disorders in children with Down syndrome. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2007;49:513-515. Webb D, Roberts I, Vyas P. Haematology of Down syndrome. Archives of Diseases of Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:503-507. Weijerman M, de Winter P. Clinical practice: The care of children with Down Syndrome. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;169:1445-1452. Winell J, Burke S. Sports participation of children with Down Syndrome. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2003;34:439-443. Image References Title Slide Image—MyChildWithoutLimits.org Website, http://www.mychildwithoutlimits.org/?page=laptop-computers Dr. John Down Image—DownSyndrome.com Website, http://downsyndrome.com/history-of-down-syndrome/ Dr. Jerome Lejeune Image—Wikipedia.org Website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_Lejeune Karyotypes and Physical Feature Images-- In B Zitelli, H Davis (Eds) Atlas of Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia:Mosby, p 9-10. Fetal Nuchal Translucency Image, Rosen T, D’Alton M. Down syndrome screening in the first and second trimesters: What do the data show? Seminars in Perinatology. 2005;29:367-375. Atrioventricular Septal Defect Diagram—MyKentuckyHeart.com Website, http://mykentuckyheart.com/information/AVCanal.htm Strabismus Image—Reece’s Rainbow Down Syndrome Adoption Ministry Website, http://reecesrainbow.org/category/waitingbycountry/russia/3region Dental Image—IntellectualDisability.info, http://www.intellectualdisability.info/physical-health/dental-problems-in-peoplewith-downs-syndrome Atlas and Axis Diagram—Atlas of Chiropractic, Rehabilitation, and Massage Therapy Website, http://www.atlascnr.com/faqs.htm Atlanto-Axial Instability Diagram—Judo and Down Syndrome Website, http://www.specialneedsjudo.eu/dis/5073/ Atlanto-Axial Instability X-ray—LearningRadiology.com Website, http://www.learningradiology.com/archives06/COW%20214-Atlantoaxial%20subluxation/atlantoaxialcorrect.htm Patellofemoral Dislocation Diagram—University of Maryland Medical Center Website, http://www.umm.edu/imagepages/9721.htm Pes Plano-Valgus Image—Medical Observer Medical Education Website, http://cmp.mcqi.com.au/ensignia/home/lms/html/Courses/HTML%20Updates/Orthopaedic%20postural%20variations%20in %20children%20-%205%20Oct%202007/Flat%20feet/Flat%20feet.html CDC Regular Growth Curve, http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/data/set1clinical/cj41l018.pdf Down Syndrome Growth Curve—Magic Foundation Website, http://www.magicfoundation.org/downloads/downsyndromegirls136monthsmedcopy422.jpg