Functionality of Collaterals : A Comparison Between Unsecured and Mutual Guaranteed Loans

advertisement

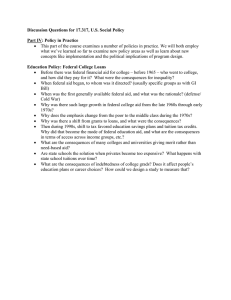

2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Functionality of Collaterals: A Comparison Between Unsecured and Mutual Guaranteed Loans Lorenzo Gai University of Florence Department of Business and Economics Mail: lorenzo.gai@unifi.it Phone: +39-328/9153073 Federica Ielasi University of Florence Department of Business and Economics Mail: federica.ielasi@unifi.it Phone: +39-339/8510987 July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 1 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Functionality of Collaterals: A Comparison Between Unsecured and Mutual Guaranteed Loans Abstract The mutual guarantee is playing an increasingly important role as an instrument of economic policy in Europe. The Mutual Loan-Guarantee Institutions (MGIs – in Italy Confidi) commit to granting a collective guarantee to credits issued to their members, who in turn take part directly or indirectly in the formation of the equity and the management of the scheme. The paper aims at understanding which characteristics of bank loans are widespread among the transactions guaranteed by MGIs, in order to verify whether the operation of this Consortia is functional to mitigate the risk of the loans. The study relates to the performing loan portfolio of 32 Italian banks. The total sample is composed of 124,267 loans, relating to the period 2008-2009. Loans guaranteed by MGIs are 14,832. They refer to guarantees granted by 28 MGIs. The empirical analysis has been conducted through the development of a stepwise logistic regression, which aims to investigate the profiles of loans related with the granting of an external guarantee. The hypothesis tested highlights the opportunities for an optimization of the guaranteed loan portfolio, through the elimination of overlapping between types of collaterals, in order to not incur in the main negative effects of an excessive level of guarantees. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 2 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The results of this study are based on an original and reserved dataset, not available in public financial statements or in public statistics, but collected directly from banks that joined the research. 1. Introduction The Mutual Loan-Guarantee Institutions (MGIs – in Italy Confidi) are “collective initiatives of a number of independent businesses or their representative organizations. They commit to granting a collective guarantee to credits issued to their members, who in turn take part directly or indirectly in the formation of the equity and the management of the scheme” (European Commission, 2005). The collective guarantees issued by these societies are now assuming an increasingly important role as an instrument of economic policy, aimed at mitigating the effects of credit rationing (Columba et al., 2010). The small business lending is the segment in which the intervention of MGIs is more effective (Beck et al., 2010). SMEs have relatively more difficulties in accessing credit, because the most significant information asymmetries that characterize the relationship with the bank, due to low reporting requirements and scarcity of public information (Tucker and Lean, 2003; Esperanca et al., 2003; Chen, 2006; Busetta and Zazzaro, 2012). Information asymmetries are typically mitigated by financial intermediaries by building relationships based on the so-called relationship lending or by asking adequate collaterals on issued loans. Both tools are more difficult to be activated towards SMEs, which, especially if they are young, have limited guarantees and a short credit history (Manove et al., 2001; Beck et al., 2005; Beck and Demirguc-Kunt, 2006). July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 3 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The intervention of MGIs should fill the inefficiencies generated by adverse selection, when debtors do not have sufficient assets to provide adequate financial guarantees or when their size does not allow the bank to carry out an in-depth screening and monitoring. In other words, MGIs “are a wealth-pooling mechanism that allows otherwise inefficiently rationed borrowers to obtain credit” (Busetta and Zazzaro, 2012). The presence of mutual guarantees is able to make a positive impact in terms of increase in functionality and liquidity of credit market, with a consequent reduction of the phenomena of credit rationing (Barro, 1976; Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981). However, the financial literature has also provided several evidences about the possible adverse effects caused by the presence of collateral for bank loans, which could negatively affect the operation of the parties involved, as well as the economic system as a whole (Jackson and Kronman, 1979, Stiglitz, 1985; Bester, 1987; Rajan and Winton , 1995; Manove and Padilla , 1999; Manove et al., 2001; Tagliavini and Lanzavecchia , 2005; Beck et al., 2005; Beck and Demirguc - Kunt, 2006; Chen, 2006). This contribution is part of the debate on the role of mutual guarantees, verifying which characteristics of the bank loans are popular among the operations guaranteed by MGIs and, consequently, the functionality of mutual guarantees in reducing potential credit rationing. The study relates to the performing loan portfolio of 32 Italian banks. The total sample is composed of 124,267 reports, relating to the period 2008-2009. The loans guaranteed by MGIs are 14,832. They refer to guarantees granted by 28 first-level mutual guarantee consorzia. The empirical analysis has been conducted through the development of a stepwise logistic regression, aimed at investigating the profiles of loans related to a significant extent to the granting of a mutual guarantee. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 4 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The conclusions highlight the opportunities for an optimization of the guaranteed loan portfolio, in particular through the elimination of the overlap between types of guarantees, in order to avoid the negative effects generated by excessive levels of collateral. The analyzes are based on an original and reserved dataset, not available in the banks’ balance sheets or in the statistics of the Supervisory Authorities, but collected directly from banks that have joined this research. The work continues with a review of the literature (Section 2) and the description of the sample and the methodology applied (paragraph 3). The fourth paragraph presents the main results obtained from the survey, while Section 5 presents the conclusions and some indications for the rationalization of banks’ guaranteed loan portfolio. 2. Literature review A large literature has discussed the role of collateral in bank loans and the relationship between the demand for guarantees and the credit risk of the company. The results are not in agreement and often not consistent with market practice. In general, it is recognized that the guarantees not only reduce the loss in the event of default, but they can promote the access to credit at the stage of granting the loan, reducing information asymmetries between funded and funder. The relationship between the level of guarantee provided and the risk of the borrower is, however, sensitive to the nature of these information asymmetries. When the risk of default of borrower is not readily observable by the bank, the guarantee is mainly used as a screening tool: granting the guarantee, the company communicates to the bank its trust and its commitment on the success of projects funded. Borrowers with less risky July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 5 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 projects are willing to grant guarantees, paying a lower interest rate, while debtors with projects characterized by a higher level of risk are willing to pay a higher interest rate, not providing collaterals (Bester, 1985; Kanatas and Chan, 1985; Bester, 1987; Besanko and Thakor, 1987; Bester, 1994). According to this literature, consequently, the guarantees are most frequently granted by safer debtors. On the other hand, when the type of borrower is more readily observable by the bank, the guarantee is primarily used to control the problem of moral hazard. Riskier is the counterpart, the most serious are these problems and, consequently, greater the demands for collateral by banks (Hempel et al., 1986; Morsman, 1986; Leeth and Scott, 1989; Berger and Udell, 1990; de Meza and Southey, 1996; Jemenez and Saurina, 2004; Chen, 2006). The secured loans are therefore those characterized by a higher probability of default. According to this literature, consistent with market practice, are the most risky borrowers to provide more guarantees. Berger and Udell (1990) also investigated the relationship between the presence of collateral and the degree of risk of the bank, concluding that the guarantee is most often associated with banks with a higher risk. The same positive correlation was found between the provided guarantees and the risk premium on loans’ pricing, as well as between collateral and the total interest rate on loans (Berger and Udell , 1990; Coco, 1999). This contribution is part of the debate on the role of collateral, verifying the correlation between the presence of a mutual guarantee and some characteristics of the firm-bank relationship (the amount of the loan, its maturity, the presence of additional collateral, the technical form of the loans…). The analysis of the potential overlap between the mutual guarantees and other forms of collateral, such as mortgages, is of primary importance in the evaluation of the lending process. In fact, the literature agrees on the existence of an equilibrium threshold in the level July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 6 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 of guarantees required to debtors (Bester, 1987; Manove and Padilla, 1999; Manove et al., 2001; Chen, 2006). An excessive amount of guarantees can produce significant negative effects: “There is an economic-efficiency case in favor of collateral limitations” (Manove et al., 2001). Regarding the positive effects, the practice of secured financing allows banks, other conditions being equal, to deal with riskier loans, facilitating access to credit for households and businesses (Barro, 1976; Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981). The presence of secured loans is not only a condition imposed by the banking system, but it is often a condition preferred from the same debtor, especially when this is a business. In fact, the instrument of external guarantee allows the entrepreneur to hold assets outside the company, pursuing the strategy summed up in the slogan “rich family-poor business”, widespread among Italian SMEs, especially in the past, for fiscal and governance reasons. However, when the guarantees required are redundant, such beneficial effects can produce disadvantages for both the lender and the borrower, as well as for the whole economic system, as discussed by extensive international literature. First, the presence of collateral may reduce the incentive for banks to achieve effective information about the counterpart (asset screening and selection) and to adequately monitor the trend of the relationship (loan monitoring) (Jackson and Kronman, 1979; Stiglitz, 1985; Rajan and Winton, 1995; Manove et al., 2001). The practice of guarantees can reduce the sensitivity of the banker to the real prospects of the financed projects, with possible negative consequences on the performance of its mediumterm loans portfolio, as witnessed by the numerous failures of the Italian special credit institutions, characterized by widely backed portfolios (Tagliavini and Lanzavecchia, 2005). The presence of substantial guarantees, moreover, does not encourage banks to forge solid, in-depth and long-term relationships with counterparts. The so-called relationship lending July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 7 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 represents an alternative to the application of guarantees to mitigate the problem of asymmetric information (Berger and Udell, 1995; Harhoff and Korting, 1998; Jemenez and Saurina, 2004; Cotugno et al., 2013). As a result, the practice of secured loans is not alien to the phenomenon of multiple bank relationships (Ongena and Smith, 2000; Tagliavini and Lanzavecchia, 2005). Chen (2006) highlights another possible adverse effects of excessive guarantees: when the amount of collateral exceeds a critical threshold, and the bank cannot request additional coverages during the renegotiation of the debt, there may be inefficiencies in the incentives of the debtor to solve its financial imbalances. In general, literature and political debate agree on the opportunity of an adequate protection of the creditor’s rights, by the posting of guarantees and/or in the context of court proceedings, but paying attention to the correct balance with the rights of the debtor, especially in terms of efficient access to credit. If the banking practice focuses on the guaranteed loans, a relative advantage is generated for the asset-based projects. A credit policy based on the guarantee with tangible goods creates a comparative disadvantage for intangible investments and innovative ones, which are not suitable to being incorporated into guaranteed schemes. Overall, the culture of secured financing may reduce opportunities for resource allocation to borrowers unable to provide adequate guarantees, including SMEs: “The difficulty of banks in assessing the creditworthiness of small borrowers often goes hand-in-hand with inadequate availability of collateralizable wealth from the latter. Lack of information and collateral therefore are universally seen as the main structural features explaining the reluctance of banks to lend to small enterprises, especially during economic downturns, with negative effects on industry dynamics, competitiveness and growth” (Busetta and Zazzaro, 2012). July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 8 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The discrimination towards small, young or innovative companies, may therefore result in the medium-term negative effects on the competitiveness of the economy (Beck et al., 2005; Beck and Demirguc - Kunt, 2006). The demand for collateral also reduces the incentive for the lender to demand proper capitalization of the company, generating potential adverse effects on the stability of the economic system, as emphasized by the literature on the relationship between the effectiveness of the instruments of credit protection and the financial structure of firms (La Porta et al., 1998; Rajan and Zingales, 1995). As noted above, the presence of collateral reduces the incentive for banks to carry out actions of screening and monitoring on the company and the family, with potential negative effects on the economic system: “collateral and screening are substitutes from the point of view of banks. Yet they are not equivalent from the social standpoint. Because of their superior expertise in project evaluation, the screening activity of banks is a value-enhancing activity for society, whereas the posting of collateral is not, since it merely allows a transfer of wealth from the borrower to the bank when things go badly” (Manove et al., 2001). The economic system as a whole, in the presence of excessive collateral, cannot rely on the fact that financial resources are invested in the best business projects, reducing the potential allocative efficiency of the loans. Finally, the presence of redundant guarantees is able to generate a negative impact on other stakeholders of the borrower, including creditors other than banks. In fact, the practice of secured loans undermines the basis of the principle of equal treatment of creditors. Outside collateral produces similar effects to an increase in share capital, but for the sole benefit of the guaranteed party. It creates a separate capitalization in favor of a particular creditor (Bolton and Scharfstein, 1996). The principle of equal treatment (par condicio creditorum) allows a wider splitting of the consequences of corporate insolvencies July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 9 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 and it is then effective for the development of the economy. However, the objective of protecting requires adequate coverage of the banks against losses resulting from business failures. The mutual guarantees is then able to mitigate some of the negative effects of excessive financial guarantees. MGIs demonstrated ability to carry out a thorough screening of the guaranteed companies, which would complement the loans selection process held by banks (Columba et al., 2010; Busetta and Zazzaro, 2012; Bartoli et al., 2012 , Gai et al., 2013) . This ability derives from an in-depth knowledge of the local business and peer pressures exerted between the different associated. However, it appears appropriate that the demand for such forms of guarantee is carefully assessed by banks and MGIs. In fact, the cost of mutual guarantee is typically only partially offset by a decrease in the rate of interest paid by the borrower (Arping, 2010). 3 . Sample and methodology The sample of this research is made up of a total of 124,267 performing loans, of which 14,832 backed by mutual guarantees. The analysed positions are included in the loans portfolio of 32 Italian cooperative banks; guarantees are issued by 28 MGIs. Since the objective of the analysis was to understand the profile of bank loans backed by mutual guarantees, in order to assess the effectiveness of the guarantee process, it was considered appropriate to analyse the loans portfolio of small banks, characterized by a similar bargaining power with respect to MGIs. The data refer to the period 2008-2009. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 10 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 We studied a series of independent variables aimed to distinguish the sub-sample of unsecured loans from the sub-sample of mutual guaranteed loans. First, the model includes variables related to the legal status of the borrower, distinguishing between households, legal entities, individual firms and co-holders. Empirical studies show a greater number of loans secured by MGIs among small and medium-sized enterprises. By consequence, it is expected that the sub-sample of guaranteed loans is particularly concentrated among legal entities and individual firms. Second, we included among independent variables the several technical forms of loans granted by banks, distinguishing between overdrafts on current accounts, advances, signature loans, instalment loans, active grants and portfolio. The different technical forms of loan enable the beneficiary to meet specific needs, such as those related to investments in fixed assets, investments in working capital or management of corporate liquidity. The presence of a significant correlation between the technical form of financing and the grant of a mutual guarantee allow to assess the effectiveness of the MGIs in supporting specific financial needs of enterprises. Finally, we included as independent variables some factors that may affect the degree of risk faced by the bank in granting the loan. The higher is the risk of collateralised transactions, the greater is the effectiveness of the MGI’s intervention. In fact, the operation of a mutual guarantee consortia should aim to increase the number of borrowers financed by the banking system, reducing the credit risk of companies otherwise excluded from access to credit, thanks to the guarantee. In particular, among the independent variables related to the credit risk of the bank we included the presence of additional forms of guarantee, with specific reference to mortgage collateral, the maturity of the loan and the amount of the granted loan. As shown in the literature on the analysis of bank credit risk, the greater is the amount of funding and the smaller the forms of guarantee obtained, the higher are the potential losses July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 11 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 given the insolvency of the borrower. The maturity of loans affects the degree of risk faced by the bank, as in the long-term the assumptions underlying the assessments of the loans are more uncertain. In the paper, we didn’t analyse variables related to the qualitative and quantitative characteristics of the borrowers, as not available. From the methodological point of view, the goal of the analysis is realized verifying the existence of significant differences between the profile of unsecured loans and the profile of mutual guaranteed ones. First of all, this analysis was done by carrying out the t-test for equality of means, in order to verify the following null hypothesis: the averages of the two sub-samples, unsecured and mutual guaranteed loans, are equal. The correlations between pairs of variables were then analysed, and finally a regression step forward model has been developed, in order to verify the variables related more significantly with the presence of a mutual guarantee. The regression model adopted, starting from a function with only the intercepts, adds the significant variables one after the other, according to the Wald statistic. In performing regression we used as the dependent variable “MG” (mutual guarantee), that takes the value 1 in the presence of a loan secured by a MGI or 0 otherwise. The objective of the analysis is to explain the different characteristics of mutual guaranteed loans, analysing three groups of independent variables, related to the legal characteristics of the borrower, the technical form of the loan granted by the bank and the degree of risk of the loan. MG = 1 / [1 + exp (- (β0 + β1 House + β2 Legal + β3 Indiv + β4 Co-holder + β5 Overdraft + β6 Advance + β7 Signat + β8 Instal + β9 Grants + β10 Portf + β11 Mortg + β12 Matur + β13 Amount))] July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 12 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 The coefficients 1, ... 13 and the intercept 0 are estimated by iterative procedure (stepwise) through the maximum likelihood method. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the variables considered. Table 1: Regression Variables Dependent Variable MG Features Dummy variable, with value 1 if the loan is guaranteed by a MGI, 0 otherwise. Independent Variable Features First category: legal status House Dummy variable , with value 1 if the loan counterpart is a household, 0 otherwise. Legal Dummy variable with value 1 if the borrower is a legal entity, 0 otherwise. Indiv Dummy variable, with value 1 if borrower is an individual firm, 0 otherwise. Co-holder Dummy variable with value 1 if the loan has co-holders, 0 otherwise . Second category: technical form Overdraft Dummy variable, with value 1 if the loan was paid in the form of current account, 0 otherwise. Advance Dummy variable, with value 1 if the loan was paid in the form of advance, 0 otherwise. Signat Dummy variable, with value 1 if the loan was paid in the form of signed credit, 0 otherwise. Instal July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK Dummy variable, with value 1 if the loan was paid in the form of 13 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 long term loan, 0 otherwise. Grants Dummy variable , with value 1if the loan was paid in the form of active grant and 0 otherwise. Portf Dummy variable , with value 1if the loan was paid in the form of portfolio, 0 otherwise. Third category: degree of risk Mortg Dummy variable, with value 1 if the loan is secured by a mortgage, 0 otherwise. Matur Variable expressed in years that states the maturity of the loan. The overdrafts are considered a with a maturity equal to 0. Amount Variable expressed in thousands of Euros that states the amount of funding approved. For further details on the characteristics of the variables, the main descriptive statistics are shown in the statistical appendix. 4 . Main results The t-test of the averages, included in the statistical appendix, shows a good divergence between the two sub-samples of mutual guaranteed and unsecured loans. As shown in the two charts below, there are significant differences the two sub-samples, especially with reference to type of borrowers. As expected, the portfolio of guaranteed positions consist almost exclusively of loans granted to legal entities and individual firms, while over a third of unsecured loans are granted to households. The principal form of loan is the instalment one in both the analysed sub-samples. The composition of secured and July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 14 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 unsecured portfolios is different with respect to other forms of loans: advances are most common among mutual guaranteed loans, while overdrafts on current accounts and signature loans have a relatively lower incidence. Graph 1 : Breakdown by type of legal status – mutual guaranteed and unsecured portfolio Graph 2: Breakdown by type of loan – mutual guaranteed and unsecured portfolio The two sub-samples have an heterogeneous composition with reference to the independent variables related to the degree of risk of the loans. Over 30% of the positions backed by mutual guarantees have a guarantee of mortgage type too. On the other hand, the sub-sample of non-guaranteed financing doesn’t have mortgage guarantees. With regard to the maturity of the loans, the unsecured portfolio is characterized by an average maturity of approximately 9 years, compared with an average maturity of less than 5 July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 15 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 years for secured loans. In order to further analyse this aspect, we eliminated from the sample all the overdrafts, for which we assumed a maturity equal to zero. Even eliminating these positions, the average maturity of unsecured loans is much higher than those backed by mutual guarantees (approximately 12 years, compared with less than 7 years). Finally, the analyses show an approved average amount much higher for non-guaranteed financing with respect to the guaranteed portfolio (approximately EUR 108,000 against EUR 68,000). These first tests show a very different profile in the two sub-samples. The results of the descriptive analysis are confirmed by the subsequent development of the regression model. The stepwise regression was interrupted at step 8, excluding from the model the legal entities and individual firms, signature loans, active grants and portfolios. Taking into account the overall percentage of correct classification and the degree of balance between the correct prediction of the two sub-samples, the step 8 of the model is considered as the most calibrated, as shown in the following table 2. The independent variables available at this step are “households”, “co-holders”, “overdrafts”, “advances”, “instalment loans”, “mortgages”, “maturity” and “amount”. Table 2: Classification table Observed Estimated Mutual guarantee 0 Step 1 Correct % 1 Mutual 0 109362 0 100,0 guarantee 1 10119 4713 31,8 Total % Step 2 91,9 Mutual 0 39509 69853 36,1 guarantee 1 352 14480 97,6 Total % Step 3 July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 43,5 Mutual 0 58645 50717 53,6 guarantee 1 404 14428 97,3 16 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Total % Step 4 58,8 Mutual 0 84411 24951 77,2 guarantee 1 3445 11387 76,8 Total % Step 5 77,1 Mutual 0 93278 16084 85,3 guarantee 1 3647 11185 75,4 Total % Step 6 84,1 Mutual 0 87542 21820 80,0 guarantee 1 2547 12285 82,8 Total % Step 7 80,4 Mutual 0 87542 21820 80,0 guarantee 1 2547 12285 82,8 Total % Step 8 80,4 Mutual 0 89281 20081 81,6 guarantee 1 2701 12131 81,8 Total % 81,7 Reference value: 0,119 On the basis of the empirical analysis, the final selected model is the following: MG = 1 / [ 1 + exp ( - ( β0 + + β1 House + β2 Co-holder + β3 Overdraft + β4 Advance + β5 Instalm + β6 Mortg + β7 Matur + β8 Amount))] The following Table 3 shows the main results of the regression model. Table 3: Stepwise logistic regression - step 8 B E.S. Wald df Sig. Exp(B) Households -3,185 ,056 3267,354 1 ,000 ,041 Co-holders -3,657 ,141 676,588 1 ,000 ,026 Overdrafts 1,287 ,150 73,861 1 ,000 3,622 Advances 1,853 ,152 149,362 1 ,000 6,377 Instalment loans 3,736 ,149 627,381 1 ,000 41,927 24,565 490,496 ,003 1 ,960 46606411717,364 Maturity -,207 ,005 2045,710 1 ,000 ,813 Amount -,002 ,000 188,979 1 ,000 ,998 Constant -3,332 ,148 507,902 1 ,000 ,036 Mortgages July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 17 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 It is interesting to see how the final model included all the variables associated with the degree of risk of the loans granted by the bank. Since the objective of the analysis is to verify the level of functionality of the intervention of MGIs, it is appropriate to carry out a study on the three independent variables related to the degree of credit risk: the presence of mortgage collaterals, the maturity and the amount of loans. An analysis of the coefficients of the regression, reported in Table 3, shows that, with reference to mortgages the sign is positive: the presence of a mortgage collateral is positively correlated with the issuing of a mutual guarantee. On the other hand, the maturity and the amount have negative signs: they are negatively correlated with the presence of a mutual guarantee. As a result, the longer is the maturity of the loans, and the greater the relative amount, much less widespread are the guarantees provided by MGIs. 5. Conclusions The analysis does lead to important conclusions, especially with regard to the degree of functionality of the mutual guarantees respect to expected loss given default for banks. Regarding the profile of counterparties backed by a mutual guarantee, the results of the empirical analysis allow us to confirm the expectations: secured loans are negatively related to loans granted to individuals and co-holders, while they are focused almost exclusively between legal entities and individual entrepreneurs. With regard to the technical forms of the loans, the analysis shows that the operation of MGIs does not affect significantly the access to credit through a particular form of financing. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 18 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Therefore, it is not supported the fulfilment of a specific financial need rather than others. The mutual guaranteed loans are mainly provided in the form of instalment loans, bank overdraft and advances, with a relative incidence not particularly dissimilar compared to unsecured loans. On the other hand, substantial differences are related to the degree of risk of the two subsamples of loans. Lacking detailed information on individual borrowers, able to express the attended probability of default, the analysis focused on the elements of the loan able to affect the level of credit risk faced by the bank, especially in terms of attended loss given default. The analysis showed a profile of the secured loans contrary to expectations. Compared to loans not secured by mutual guarantee, in fact, guaranteed loans are often covered by mortgages and they are loans of shorter maturity and lower amount. With reference to the analysed risk profiles, certainly partial, the survey shows a major operation of MGIs in the coverage of loans characterized, other conditions being equal, by a lower degree of risk for the bank. In contrast to the recommendations of the literature, then, it seems that MGIs do not go to guarantee those loans characterized by a higher risk profile, which would not have been access to finance in the absence of external guarantee. It should be emphasized that this results can be influenced by the degree of risk of the counterparties in terms of probability of default. In other words, the concentration of mutual guarantees among loans characterized by a lower loss in the event of default could be motivated by the widespread presence of mutual guarantees among counterparties characterized by a particularly high probability of default. Because the credit risk is the product of the borrower’s probability of default and the loss given default, it is possible that the MGIs wish to compensate for the higher risk of default of counterparties with a greater portfolio diversification and a specific attention to loss given default. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 19 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 However, this modus operandi is ineffective for the banking system and it penalizes businesses. Particular attention should be given to the combined presence of mortgages and mutual guarantees. In the development of stepwise regression, the independent variable “mortgage” is the one selected at the first step of the model construction. It is therefore an important factor that affect the profile of the mutual guaranteed loans. Out of a total of approximately 500 million Euros of exposure guaranteed by MGIs on 31.12.2009, about 198 million were secured by real estate mortgage too. This condition is inefficient for the banking system, as it weakens the effects of the presence of MGIs in terms of capital allocation. As shown in Table 4, starting in 2009, the banks included in the sample have chosen to focus on eligible collaterals, for the purposes of limiting capital absorption for the credit risk. In fact, first demand guarantees (Basel compliant) show a strong growth from 2008 and 2009. Table 4: Total stock broken down by type of guarantee Stock 2008 (€) Stock 2008 Stock 2009 (€) (%) Stock 2009 (%) First demand guarantee 42.097.909 17% 208.783.658 42% Subsidiary/ segregated 205.480.148 83% 291.701.264 58% 247.578.057 100% 500.484.922 100% guarantee Total However, since typically the mortgage guarantee covers all or a significant portion of the exposure, such form of “double coverage” is inefficient from the point of view of capital requirements. In this case, the mutual guarantee, even if released at first demand from a supervised MGI subject, it doesn’t act as an additional tool for reducing capital absorption for the beneficiary bank. As a result, the banks make a sub-optimal management of credit risk July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 20 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 mitigation instruments. On the contrary, they would take advantage of the mortgages only in the absence of an eligible mutual guarantee issued by a supervised Consortia. The optimization of the guaranteed portfolio would also allow customers to not pay costs, explicit and implicit, of the provision of a double guarantee, reducing the overall pricing of loans and facilitating access to credit for those individuals who do not have mortgage collaterals. A solution to the problem of “double coverage” would also improve the functionality of MGIs, whose operations would be directly channeled towards firms which are otherwise excluded from bank financing. References AECM, Guarantees and the recovery: the impact of anti-crisis guarantee measures. Tech. Rep., Association Européenne du Cautionnement Mutuel, available at http://www.aecm.be, 2010 Arping S., The pricing of bank debt guarantees, Journal of Financial Stability, No. 108, 2010. Beck T., Demirguç-Kunt A., Small and medium-size enterprises: access to finance as a growth constraint, Journal of Banking and Finance, no. 30 (11), 2006. Beck T., Demirguç-Kunt A., Maksimovic V., Financial and legal constraints to firm growth: does firm size matter?, Journal of Finance, no. 60 (1), 2005. Benavente, J.M, Galetovic A., Sanhueza R., Fogape: an economic analysis, University of Chile Economics Department Working Paper 222, 2006. Berger A.N., Udell G.F., Collateral, loan quality, and bank risk, Journal of Monetary Economics, no. 25, 1990. Berger A.N., Udell G.F., Relationship lending and lines of credit in small business finance, Journal of Business, Vol. 68, 1995. Besanko D., Thakor A.V., Collateral and rationing: sorting equilibria in monopolistic and competitive credit markets, International economic review, Vol. 28, No. 3, 1987. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 21 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Bester H., Screening vs. rationing in credit markets with imperfect information, American Economic Review, No. 75, 1985. Bester H., The role of collateral in credit market with imperfect information, European Economic Review, no. 31, 1987. Bolton P., Scharfstein D.S., Optimal debt structure and the number of creditors, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 104, 1996. Busetta G., Zazzaro A., Mutual loan-guarantee societies in monopolistic credit markets with adverse selection, Journal of Financial Stability, no. 8, 2012. Chan Y., Kanatas G., Asymmetric valuation and the role of collateral in loan agreements, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, No. 17, 1985. Chen Y., Collateral, loan guarantees, and the lenders’incentives to resolve financial distress, The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, no. 46, 2006. Coco G., Collateral, heterogeneity in risk attitude and the credit market equilibrium, European Economic Review, no. 43, 1999. Columba F., Gambacorta L., Mistrulli P.E., Mutual guarantee institutions and small business finance, Journal of Financial Stability, no. 6, 2010. Cotugno M., Monferrà S., Sampagnaro G., Relationship lending, hierarchical distance and credit tightening: Evidence from the financial crisis, Journal of Banking and Finance, No. 37, 2013. de Meza D., Southey C., The borrower’s curse: optimism, finance and entrepreneurship, The Economic Journal, No. 106, 1996. Esperanca J.P., Gama A.P.M., Gulamhussen M.A., Corporate policy of small firms: an empirical (re)examination, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, No. 10, 2003. European Commission, Guarantees and mutual guarantees. Best report: report to the Commission by an independent expert group. Tech Rep., available at http://ec.europa.eu, 2006. Gai L., Ielasi F., Rossi F., Mutual Guaranteed Loans in Italy: the determinants of defaults, Cambridge Business and Economics Conference, 2013. Harhoff D., Korting T., Lending relationships in Germany – Empirical evidence from survey data, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 22, 1998. Hempel G., Coleman A., Simonson D., Bank management, Wiley, 1986. Jackson T.H., Kronman A.T., Secured financing and priorities among creditors, Yale Law Journal, No. 88, 1979. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 22 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Jemenéz G., Saurina J., Collateral, type of lender and relationship banking as determinants of credit risk, Journal of Banking & Finance, no. 28, 2004. La Porta R., Lopez-De-Silanes F., Shleifer A., Vishny R.W., Law and finance, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 106, n.6, 1998. Manove M., Padilla A.J., Banking (conservatively) with optimists, The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 30, No. 2, 1999. Manove M., Padilla A.J., Pagano M., Collateral versus project screening: a model of lazy banks, The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2001. Morsman E. Jr., Commercial loan structuring, Journal of Commercial Bank Lending, No. 6810, 1986. Ongena S., Smith D.C., What Determines the Number of Bank Relationships? Cross-Country Evidence, Journal of Financial Intermediation, No.9, 2000. Rajan R., Winton A., Covenants and Collateral as Incentives to Monitor, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 50, No. 4, 1995. Rajan R., Zingales L., What do we know about capital structure: some evidence from international data, in Journal of Finance, Vol. 50, No. 5, 1995. Stein J., Prices and trading volume in the housing market: A model with downpayment effects, in Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol.110, No.2, 1995. Stiglitz J., Money, credit and banking lecture, in Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol.17, n.2, 1985. Stiglitz J., Weiss A., Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information, in American Economic Review, vol. 71, n.3, 1981. Tagliavini G., Lanzavecchia A., Garanzie opportune, garanzie controproducenti, Banca, Impresa e Società, No. 3, 2005. Tucker J., Lean J., Small firm finance and public policy, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, No. 10, 2003. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 23 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Statistical Appendix Descriptive Statistics N July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK Minimum Maximum Average Std. deviation Mutual guarantee 124267 0 1 ,12 ,324 Household 124267 0 1 ,32 ,468 Legal entities 124267 0 1 ,32 ,467 Individual firms 124267 0 1 ,20 ,401 Co-holders 124267 0 1 ,15 ,362 Overdrafts 124267 0 1 ,21 ,405 Advances 124267 0 1 ,06 ,236 Signature loans 124267 0 1 ,02 ,144 Instalment loans 124267 0 1 ,71 ,456 Active grants 124267 0 1 ,00 ,024 Portfolio 124267 0 1 ,01 ,079 Mortgages 124194 0 1 ,04 ,191 Maturity 124267 0 40 8,55 7,691 Amount 124267 ,2419 66750,0000 103,411637 296,5764993 24 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Levene's test for equality of variances F Sig. T-test of means for independent samples t-test for equality of means t df Sig. (2- Difference Standard error Confidence interval for the tailed) between difference difference at 95% averages Equal Households variances 98418,304 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Legal entities variances 2838,962 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Individual firms variances 8917,017 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Co-holders variances 18054,308 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Overdrafts variances 368,767 ,000 Not equal variances Advances July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK Equal variances 2050,109 ,000 Lower Upper 80,424 124265 ,000 ,321 ,004 ,313 ,329 147,578 44445,354 ,000 ,321 ,002 ,317 ,325 -64,616 124265 ,000 -,259 ,004 -,267 -,252 -60,210 18325,994 ,000 -,259 ,004 -,268 -,251 -66,426 124265 ,000 -,229 ,003 -,236 -,222 -54,717 17317,035 ,000 -,229 ,004 -,237 -,221 53,623 124265 ,000 ,168 ,003 ,162 ,174 125,194 103127,248 ,000 ,168 ,001 ,165 ,170 9,204 124265 ,000 ,033 ,004 ,026 ,040 9,662 19686,492 ,000 ,033 ,003 ,026 ,039 -23,446 124265 ,000 -,048 ,002 -,052 -,044 25 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Not equal variances Equal Signature loans variances 1132,820 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Instalment loans variances 31,970 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Active grants variances 22,501 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Portfolio variances 254,058 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Mortgages variances 713842,489 ,000 Not equal variances Equal Maturity variances 12020,184 ,000 Not equal variances Amount July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK Equal variances 243,758 ,000 -18,768 17125,474 ,000 -,048 ,003 -,053 -,043 16,483 124265 ,000 ,021 ,001 ,018 ,023 32,546 55472,189 ,000 ,021 ,001 ,019 ,022 -2,771 124265 ,006 -,011 ,004 -,019 -,003 -2,794 19177,676 ,005 -,011 ,004 -,019 -,003 2,371 124265 ,018 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,001 4,068 37527,808 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,001 7,928 124265 ,000 ,005 ,001 ,004 ,007 13,609 37566,713 ,000 ,005 ,000 ,005 ,006 -225,689 124192 ,000 -,318 ,001 -,321 -,315 -83,112 14831,000 ,000 -,318 ,004 -,325 -,310 64,837 124265 ,000 4,291 ,066 4,162 4,421 102,564 31710,639 ,000 4,291 ,042 4,209 4,373 15,547 124265 ,000 40,3044733 2,5924863 35,2232457 45,3857009 26 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Not equal 29,209 variances 47519,876 ,000 40,3044733 1,3798689 37,5999118 43,0090347 Correlations between pairs of variables Mutual Households guarantee Households Legal entities Legal Individual Co- Overdrafts Advances Signature Instalment Active Portfolio Mortgages Maturity Amount entities firms holders loans grants -,222 1,000 -,474 -,347 -,296 -,126 -,167 -,063 ,224 -,011 -,025 -,115 ,190 -,073 ,180 -,474 1,000 -,345 -,294 ,204 ,235 ,106 -,339 ,029 ,006 ,085 -,341 ,130 Individual Pearson’s Correlation firms Co-holders ,185 -,347 -,345 1,000 -,215 ,075 ,018 -,001 -,084 -,012 ,048 ,105 -,157 -,069 -,150 -,296 -,294 -,215 1,000 -,183 -,107 -,054 ,241 -,009 -,029 -,079 ,368 ,004 Overdrafts -,026 -,126 ,204 ,075 -,183 1,000 -,128 -,075 -,791 -,012 -,041 -,026 -,534 -,052 Advances ,066 -,167 ,235 ,018 -,107 -,128 1,000 -,037 -,389 -,006 -,020 ,022 -,278 ,007 Signature -,047 -,063 ,106 -,001 -,054 -,075 -,037 1,000 -,228 -,004 -,012 -,025 -,067 ,018 ,008 ,224 -,339 -,084 ,241 -,791 -,389 -,228 1,000 -,037 -,123 ,023 ,653 ,034 -,007 -,011 ,029 -,012 -,009 -,012 -,006 -,004 -,037 1,000 -,002 -,003 -,020 ,122 -,022 -,025 ,006 ,048 -,029 -,041 -,020 -,012 -,123 -,002 1,000 -,013 -,068 -,019 ,539 -,115 ,085 ,105 -,079 -,026 ,022 -,025 ,023 -,003 -,013 1,000 -,059 -,008 Maturity -,181 ,190 -,341 -,157 ,368 -,534 -,278 -,067 ,653 -,020 -,068 -,059 1,000 ,144 Amount -,044 -,073 ,130 -,069 ,004 -,052 ,007 ,018 ,034 ,122 -,019 -,008 ,144 1,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,013 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,000 ,354 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,001 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,092 Instalment loans Active grants Portfolio Mortgages Households Sig. (1 tail) Legal entities Individual firms Co-holders July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 27 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Overdrafts ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 Advances ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,017 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,011 Signature ,000 ,000 ,000 ,354 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,108 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,003 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,009 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,001 ,000 ,017 ,108 ,000 . ,251 ,146 ,000 ,000 Portfolio ,000 ,000 ,013 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,251 . ,000 ,000 ,000 Mortgages ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,146 ,000 . ,000 ,004 Maturity ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 . ,000 Amount ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,092 ,000 ,011 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,000 ,004 ,000 . Instalment loans Active grants Variables in the equation Step 1a Step 2b B E.S. Wald df Sig. Mortgages 23,583 585,466 ,002 1 ,968 Constant -2,380 ,010 52474,685 1 ,000 ,093 Households -2,753 ,055 2541,297 1 ,000 ,064 Mortgages 23,641 556,476 ,002 1 ,966 Constant -1,967 ,011 33166,696 1 ,000 ,140 Households -3,068 ,055 3149,353 1 ,000 ,047 Co-holders -4,255 ,139 933,192 1 ,000 ,014 Mortgages 23,728 534,203 ,002 1 ,965 Constant -1,653 ,011 22266,896 1 ,000 ,192 Households -3,315 ,055 3623,445 1 ,000 ,036 Co-holders -4,566 ,140 1071,216 1 ,000 ,010 Step 3c Step 4d July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 28 Exp(B) 17459389244,3 83 18508483846,8 27 20185947240,0 18 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics Instalment loans ,814 ,023 1204,784 1 ,000 Mortgages 23,708 527,777 ,002 1 ,964 Constant -2,134 ,019 12523,377 1 ,000 ,118 Households -3,131 ,056 3177,026 1 ,000 ,044 Co-holders -3,554 ,140 641,098 1 ,000 ,029 2,507 ,035 5098,450 1 ,000 12,271 24,729 488,926 ,003 1 ,960 Maturity -,240 ,004 3122,116 1 ,000 ,787 Constant -2,030 ,019 11219,755 1 ,000 ,131 Households -3,117 ,056 3141,892 1 ,000 ,044 Co-holders -3,552 ,140 640,245 1 ,000 ,029 ,553 ,040 186,268 1 ,000 1,738 2,661 ,038 5015,195 1 ,000 14,313 24,706 489,216 ,003 1 ,960 Maturity -,238 ,004 3083,415 1 ,000 ,788 Constant -2,196 ,024 8550,986 1 ,000 ,111 Households -3,117 ,056 3145,102 1 ,000 ,044 Co-holders -3,562 ,140 643,693 1 ,000 ,028 Overdrafts 1,264 ,150 71,309 1 ,000 3,540 Advances 1,757 ,151 134,762 1 ,000 5,796 Instalment loans 3,842 ,149 662,950 1 ,000 46,616 24,690 489,708 ,003 1 ,960 Maturity -,234 ,004 2992,352 1 ,000 ,791 Constant -3,401 ,148 529,527 1 ,000 ,033 Households -3,185 ,056 3267,354 1 ,000 ,041 Instalment loans Step 5e Mortgages Advances Step 6f Instalment loans Mortgages Step 7g Mortgages Step 8h July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK ISBN : 9780974211428 29 2,256 19779694765,5 89 54889291025,0 43 53685892858,5 93 52813576837,7 92 2014 Cambridge Conference Business & Economics ISBN : 9780974211428 Co-holders -3,657 ,141 676,588 1 ,000 ,026 Overdrafts 1,287 ,150 73,861 1 ,000 3,622 Advances 1,853 ,152 149,362 1 ,000 6,377 Instalment loans 3,736 ,149 627,381 1 ,000 41,927 24,565 490,496 ,003 1 ,960 Maturity -,207 ,005 2045,710 1 ,000 ,813 Amount -,002 ,000 188,979 1 ,000 ,998 Constant -3,332 ,148 507,902 1 ,000 ,036 Mortgages a. Variable included in the step 1: Mortgages. b. Variable included in the step 2: Households. c. Variable included in the step 3: Co-holders. d. Variable included in the step 4: Instalment loans. e. Variable included in the step 5: Maturity. f. Variable included in the step 6: Advances. g. Variable included in the step 7: Overdrafts. h. Variable included in the step 8: Amount. July 1-2, 2014 Cambridge, UK 30 46606411717,3 64