Quebec_Bridge_collapse.doc

advertisement

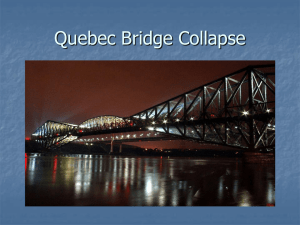

Quebec Bridge collapse Introduction: Quebec Bridge collapsed on the 29th of August 1907 at 5.30pm, just after the first end of day work whistle had blown. Out of the 86 men working on the Bridge at the time of the collapse 75 were killed. Just as the men were waiting for the second work whistle to blow they heard a loud bang, two compression cables had failed. Prelude to the collapse of the bridge: The bridge was proposed in 1897. Theodore Cooper went to inspect the proposed site of the new Bridge. He was a well respected Bridge engineer. He had completed many projects successfully but wanted a monumental project to end his career. He was known throughout America as one of the best Bridge engineers. He put himself forward to engineer the Quebec Bridge; his tender went basically unchallenged due to his reputation. The Quebec Bridge company was happy with this as their own project engineer, Edward Hoare, had never built a bridge with a span larger than 300 feet. Cooper was put in charge of selecting a design and tender for the bridge but he had little choice. The Quebec Bridge company worked closely with the Phoenix Bridge Company of Phoenixville on all projects and QBC were biased toward other them. QBC picked their design without giving other tenders fair consideration. The Phoenix Bridge design was described as “the best and the cheapest” which suited QBC as they had little funds. On May 6, 1900, Cooper was appointed the company's consulting engineer for the duration of the work. John Sterling Deans, the chief engineer of the Phoenix Bridge Company, and Edward Hoare worked close together on the Quebec Bridge design and they both answered to Cooper. Cooper decided to span the Bridge a further 200 feet than the original design had intended. In Cooper’s opinion there would be less ice flow damage to the bridge during winter, plus the bridge would be cheaper and reduce the construction time by a year. Cooper decided the extra weight of the200 feet was covered in the safety factor in the design, so no calculations were done considering the extra span and weight of the bridge. Cooper only visited the site 3 times; May 1903 was his last visit. He then oversaw the project from his office in New York. During a visit to Ottawa, Collingwoods Schreiber, the chief engineer of Railways and canals, had the final specifications for Quebec bridge reviewed. He expressed his concern about the high stresses. Unfortunately, because of everybody’s belief in Coopers Experience they did not question the design. Cooper then appointed a recently graduated engineer, Norman McLure, with no experience, to be his eyes and ears on site for the rest of the construction of the Bridge. McLure came well recommended and had the technical knowhow to report to Cooper accurately. On Feb the 1st, 1906, Cooper received a report from the Phoenix Bridge Company’s inspector of materials, Edwards, indicating that the projected weight of the steel was 11 million pounds heavier than previously estimated. Cooper concluded that Edwards was wrong by 7 to 10%. At the time Cooper received this report the south anchor arm, tower, and two panels of the south cantilever arm had been fabricated, and six panels of the anchor arm were already in place. The only way to remedy these findings would have been to start again; Cooper decided the increase of stress was acceptable. The collapse: The Quebec Bridge was to have a span of 1800 feet, the longest in the world at the time. The first opportunity to perform critical computations of the bridge’s weight was during the long waiting period between 1900 and 1903. It was also an opportunity to carry out preliminary tests and research studies, none of which were carried out because it was not in the interests of the Phoenix Bridge Company to spend money on research costs it might never recoup, and it was impossible for the Quebec Bridge Company to provide the funds. An unspoken assumption became necessary instead: Theodore Cooper's experience and authority were sufficient to confer success upon the untested work. Then in 1903 the Canadian government guaranteed a bond issue of $6.7 million to pay for the work and by 1905 the shop drawings of the south anchor arm were completed and it would have been possible to recalculate the weight of the arm, neither the Phoenix Bridge Company nor Theodore Cooper bothered to do it--now for the second time. Three years of opportunity for deliberate preparation had been lost. In the rush to provide drawings so that the steel for the bridge could be fabricated with little loss of time, there was no re-computation of assumed weights for the bridge under the revised specifications. It was an oversight of critical importance, and Theodore Cooper did not intervene. He decided to accept the theoretical estimates of weight that the Phoenix Bridge Company had provided. By the summer of 1907 the consequences of allowing the bridge's actual dead load to go uncalculated for so long began to show up on the structure itself, in the lower chord compression members--the lower outside horizontal pieces running the length of the bridge. In riveting the bottom chord splices of the south arm, they were having some trouble on account of the faced ends of the two middle ribs not matching...This had occurred in four instances so far, but by using two 75-ton jacks they were partly able to straighten out these splices, but not altogether. In July 1907 work on the central suspended span began. As the span crept out over the river the stresses on the compression members farther back became intolerable. latticed compression members in a major work under construction was poorly understood then, so key portions at the ends of the Quebec Bridge's weight-bearing lower chords were still unriveted, even as the stresses upon them grew insupportable with the steady outward advance of the span. By early august two of the lower compression chords were showing signs of buckling. Two of the chords from the south cantilever arm were bent. By 12th august the splice between two adjacent compression chords was now bent as well. The chief engineer in Phoenixville however insisted that those chords were bent when they left the shop but that they were still serviceable. McClure, Cooper’s representative on the site insisted that they only began to show signs of deflection after being installed on the bridge. On august 20th one of the compression chords was out of line by only three quarters of an inch, and a week later it was two and a quarter inches out of line. The Phoenixville bridge company continued to insist that the compression chords were bent during fabrication but they made no attempt to explain how the deflection had grown by an inch and a half in just a week. When cooper learned of the deflection he immediately sent a telegraph to Phoenixville instructing them not to add any more load to the bridge until after “due consideration of facts”. Word was never sent to Quebec however to call off work on the bridge.When the telegraph reached Phoenixville the chief engineer (john deans) read it and disregarded it and so work on the bridge continued. Then on august 29th at 5:30pm the bridge finally collapsed. With a loud bang, two compression chords in the south anchor arm of the bridge failed, either by the rupture of their latticing or by the shearing of their lattice rivets, and the 19,000 tons of the south anchor arm, cantilever arms, and the partially completed centre span crashed into the river. The error was made in assuming the dead load for the calculations at too low a value (11000 pounds too low)...This error was of sufficient magnitude to have required the condemnation of the bridge, even if the details of the lower chords had been of sufficient strength. And to have started again from scratch. A second collapse of the Quebec bridge occurred in 1916, during the construction of the second Quebec bridge (now two and a half times heavier than its predecessor). The central span which was pre-fabricated dropped into the river while being lifted into place, killing eleven men. Conclusion: Although the Quebec Bridge collapsed due to an excess of dead load and strain on key chord members this could have been avoided if correct processes were put in place at the offset of the project. The fact that Theodore Cooper’s reputation in the field of bridges was so great there was nobody to question his calculations. When the 200 extra feet was added onto the original design Cooper had been so confident of the structures stability that he didn’t even check the calculations himself. The fact that it went from 62 to 73 million pounds of steel when this extension was taken into account let to very high unit stresses along key members, which ultimately led to failure and 75 deaths. Another component that aided the failure of the structure was that key portions at the ends of the weight bearing lower chords were still unriveted. Although this was due to an inadequate knowledge in the area at that time and as such blame cannot be apportioned to any individual. The lack of communication contributed greatly to the failure. Having the head engineer hundreds of miles away in a New York office was a far from ideal situation. Also having the two engineers on site being so underqualifed (one was a graduate and the other had never built a bridge greater than 300 ft) meant that if a key decision had to be made quickly it was made by these two and a report sent to New York for Cooper to analyse. Had Cooper visited the site more than 3 times he most likely would have noticed the large deflections as a precursor to failure and could have halted construction or alter the design sufficiently enough so as to make the structure stable.