Congress.doc

advertisement

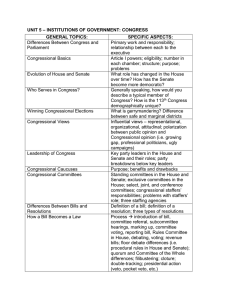

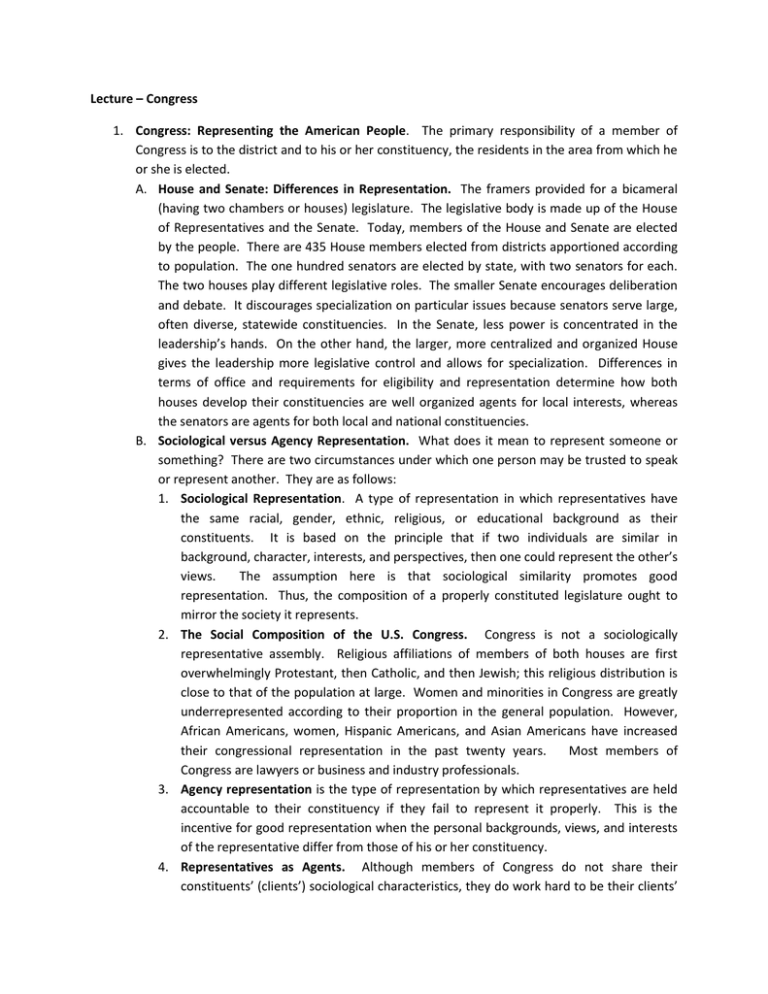

Lecture – Congress

1. Congress: Representing the American People. The primary responsibility of a member of

Congress is to the district and to his or her constituency, the residents in the area from which he

or she is elected.

A. House and Senate: Differences in Representation. The framers provided for a bicameral

(having two chambers or houses) legislature. The legislative body is made up of the House

of Representatives and the Senate. Today, members of the House and Senate are elected

by the people. There are 435 House members elected from districts apportioned according

to population. The one hundred senators are elected by state, with two senators for each.

The two houses play different legislative roles. The smaller Senate encourages deliberation

and debate. It discourages specialization on particular issues because senators serve large,

often diverse, statewide constituencies. In the Senate, less power is concentrated in the

leadership’s hands. On the other hand, the larger, more centralized and organized House

gives the leadership more legislative control and allows for specialization. Differences in

terms of office and requirements for eligibility and representation determine how both

houses develop their constituencies are well organized agents for local interests, whereas

the senators are agents for both local and national constituencies.

B. Sociological versus Agency Representation. What does it mean to represent someone or

something? There are two circumstances under which one person may be trusted to speak

or represent another. They are as follows:

1. Sociological Representation. A type of representation in which representatives have

the same racial, gender, ethnic, religious, or educational background as their

constituents. It is based on the principle that if two individuals are similar in

background, character, interests, and perspectives, then one could represent the other’s

views.

The assumption here is that sociological similarity promotes good

representation. Thus, the composition of a properly constituted legislature ought to

mirror the society it represents.

2. The Social Composition of the U.S. Congress. Congress is not a sociologically

representative assembly. Religious affiliations of members of both houses are first

overwhelmingly Protestant, then Catholic, and then Jewish; this religious distribution is

close to that of the population at large. Women and minorities in Congress are greatly

underrepresented according to their proportion in the general population. However,

African Americans, women, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans have increased

their congressional representation in the past twenty years.

Most members of

Congress are lawyers or business and industry professionals.

3. Agency representation is the type of representation by which representatives are held

accountable to their constituency if they fail to represent it properly. This is the

incentive for good representation when the personal backgrounds, views, and interests

of the representative differ from those of his or her constituency.

4. Representatives as Agents. Although members of Congress do not share their

constituents’ (clients’) sociological characteristics, they do work hard to be their clients’

agents and serve their interests in the governmental process. This can be seen in the

constant client-agent communication and in the sizable increase in House and Senate

staffers employed in district offices, many of whom spend their time consumed by client

service, or casework. Members often vote along with their districts’ interests. Still,

many constituents do not have strong views about every issue. Therefore,

representatives are free act as they think best. The power of an agent is not unlimited,

however. Constituents also influence legislative votes, because representatives who go

against district wishes are unlikely to be reelected.

C. The Electoral Connection. Three factors related to the electoral system affect who gets

elected and what they do in office.

1. Who runs for office? Voters’ choices are restricted by who decides to run for office.

Today, political parties ensure that well qualified candidates run for Congress, but

running for office is a personal choice ignited by the individual’s ambition, potential for

raising funds, and support.

2. Incumbency. This is defined as holding the political office for which one is running.

Incumbents provide constituents with services to ensure reelection. The services

include taking care of individual requests and regular communications with constituents

to establish a personal relationship with them. The success of this strategy is evident in

the high re-election rats. Incumbency can help a candidate by scaring off potential

challengers. The advantage of incumbency preserves the status quo in Congress and

keeps the social composition of Congress consistent. Therefore, supporters of term

limits (legally prescribed limits on the number of terms an elected official can serve)

argue that such limits are the only way to get new faces in Congress. However, because

of retirement, on average 10 percent of members of Congress retire each election.

3. Apportionment and Redistricting. The last factor affecting congressional seats is the

way congressional districts are drawn. The number of House seats is set at 435.

Apportionment is the process, occurring after every decennial census, which allocates

congressional seats among the fifty states according to population changes. Therefore,

states whose population grows gain seats and states whose population declines lose

seats. Redistricting is the process of redrawing election districts and redistributing

legislative representatives. This happens every ten years to reflect population shifts or

in response to legal challenges to existing districts. Redistricting can be a highly political

process because districts can be shaped to create an advantage for the majority party in

the legislature, which controls the redistricting process. Redistricting can also give an

advantage to one party by clustering voters with some ideological or sociological

characteristics in a single district, or by separating those voters into two or more

districts. The manipulation of electoral districts to serve the interests of a particular

group is known as gerrymandering. After the 1964 Civil Rights Act, race became a major

and controversial consideration in redistricting (e.g., the creation of minority-majority

districts to increase minority representation in Congress). However, in the 1995 case of

Miller v. Johnson, the Supreme Court limited racial redistricting and stated that race

cannot be the predominant factor in drawing electoral district lines.

D. Direct Patronage. Congress members often have the opportunity to provide direct benefits

or patronage for their constituents. The most important legislative patronage opportunity

is called the pork barrel, a type of appropriation that specifies a project to be funded within

a particular district. The ability bring home “pork” to one’s district contributes positively to

a member’s chance of re-election. Congress members introduce “earmarks” in legislation

that provide special benefits for their constituents. Highway bills are a favorite vehicle for

congressional pork barrel spending.

In 2007, the House passed a new ethics rule requiring those representatives supporting

particular earmarks to identify themselves and guarantee that they had no personal

financial stake in the requested project. The new requirements seem to have had some

impact, for example cutting in half the vale of earmarks included in a 2007 defense spending

bill. President Obama has called for Congress to publish a list of all earmark requests on a

single website.

A limited amount of other direct patronage exists. For example, a form of constituency

service is intervention with federal administrative agencies on constituents’ behalf. A

different form of patronage is the private bill – a congressional proposal to provide a specific

person with some kind of relief, a special privilege, or a special exemption. This privilege is

often abused but is hard to curtail because it is the easiest, cheapest, and most effective

form of congressional patronage and contributes to members’ re-election chances.

2. The Organization of Congress. To exercise its power to make the law, Congress must first

organize. The building blocks of congressional organization include the political parties, the

committee system, congressional staff, the caucuses, and the parliamentary rules of the House

and the Senate. Each of these play a key role in congressional organization and legislative

formulation.

A (political) caucus or conference is a legislative or political group’s closed meeting for selecting

candidates, planning strategy, or making decisions regarding legislative matters. Every two,

years, at the beginning of a new Congress, each party gathers and elects its House leaders. The

House Republicans’ gathering is called the conference. Democrats call their gathering the

caucus.

A. Party Leadership in the House. The elected majority leader is automatically elected by the

whole House as the Speaker of the House, the chief presiding officer of the House of

Representatives. The Speaker is elected at the beginning of every Congress. The Speaker is

the most important party and House leader and can influence the legislative agenda, the

fate of individual pieces of legislation, and members’ positions within the House and

committee assignments.

The House majority then elects a majority leader, while the minority party elects a minority

leader. In the House, the majority leader is subordinate in the party hierarchy to the

Speaker of the House. Both parties also elect whips to line up party members on votes and

convey voting information to the leaders.

B. Party Leadership in the Senate. In the Senate, the office of the president pro tempore is a

ceremonial position, held by the most senior member of the majority party. In the Senate,

the real power lies in the hands of the majority leader and minority leader, who perform

tasks equivalent to their counterparts in the House. Along with these organizational tasks,

congressional party leaders may control or try to set the legislative agenda.

C. The Committee System. The committee system is central to congressional operation.

Congress relies on committees to do the work of building legislation. There are different

types of committees:

1. Standing committees are permanent in nature. They have the power to propose and

write legislation. The jurisdiction of each standing committee covers particular subject

matter, such as finance, tax, trade, Social Security, and Medicare. Among the most

important standing committees are those in charge of finances, such as taxation and

trade. Appropriations committees also play important roles because they decide how

much funding various programs will actually receive. The House Rules committee allots

debate time and sets floor amendments rules.

2. Select committees. These are usually temporary legislative committees set up to

highlight, investigate, or address a particular issue not within the jurisdiction of existing

committees.

3. Joint committees are legislative committees formed by members of both the House and

Senate. There are four of these committees concerned with economics, taxation,

library, and printing. Joint committees play important information gathering roles.

4. Conference committees are temporary joint committees created to work out a

compromise on the House and Senate versions of a piece of legislation. These

committees are important for reconciling differences between House and Senate

legislation.

D. Politics and the Organization of Committees. Each committee’s hierarchy is usually based

on seniority, an individual’s ranking based on the length of continuous service on a

congressional committee. From time to time, both parties have departed from the seniority

system to foster other legislative and electoral goals. Over the years, Congress has changed

its original structure and operating procedures. Among those changes is the increase in

subcommittees that are responsible for considering a specific subset of issues under a

committee’s jurisdiction. This change was made to reduce the power of committee chairs.

However, it brought power fragmentation problems, making it more difficult to reach

legislative agreement.

In 2001, the Republican House reduced the number of

subcommittees and instituted limits on the number of times a member could serve as a

committee chair. When the Democrats became the majority party in 2007, they kept many

of these reforms.

Sharp partisan divisions among members of Congress have made it difficult to deliberate

and bring bipartisan expertise to bear on policy making as it has in the past. With

committees less able to engage in effective decision making and often unable to act, it has

become more common in recent years for party driven legislation to go directly to the floor,

bypassing committees.

E. The Staff System: Staffers and Agencies. Every congress member employs many staff

members whose tasks include handling constituency requests and, to a large and growing

extent, dealing with legislative details and the activities of administrative agencies. In

addition to their personal staff, senators and representatives employ committee staffers

who are responsible for administering the committee’s work, such as research, scheduling,

and organizing the legislative process. Congress also established staff agencies or legislative

support agencies responsible for policy analysis. These agencies help Congress oversee the

executive branch; they include the Congressional Research Service, the Congressional

Budget Office, and the Government Accountability Office, among others.

F. Informal Organization: The Caucuses. In addition to the official congressional organization,

there is an unofficial structure – the caucuses. A congressional caucus is an association of

congressional members based on party, interest, or social group, such as gender or race.

They seek to advance the interests of the groups they represent by promoting legislation,

hearings, and favorable treatment. Some caucuses have evolved into powerful lobbying

organizations.

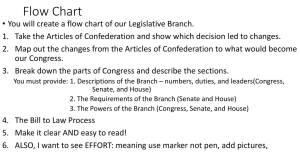

3. Rules of Lawmaking: How a Bill Becomes a Law. The rules for congressional procedure are

important to the legislative process. These rules govern the process from the introduction of a

bill (a proposed law that has been sponsored by a congressional member and submitted to the

clerk of the House or Senate) all the way to the submission to the president for signature.

A. Committee Deliberation. The first step to pass a law is to draft the bill. These drafts are

then submitted to the appropriate committee for deliberation. Then the committee refers

the bill to a subcommittee. It may hold hearings, testimony, and markup (revision) sessions

before the next step – passing the bill up to the full committee for markup and a vote.

Many bills are simply allowed to “die in committee” with little or no serious consideration

given to them. The handful of bills reported out of committees must pass the Rules

Committee. The Rules Committee allots debate time and floor amendments rules. The

committee may attach a closed rule (a provision limiting or prohibiting the introduction of

amendments during the bill’s floor debate) or an open rule (a provision that permits floor

debate and the addition of new amendments to a bill). Senate rules are more relaxed,

reflecting the deliberative character of that chamber.

B. Debate. The next step in passing a law is debate of the bill on the floor of the House and

Senate. The Speaker of the House and the Senate majority leader have the power of

recognition during the bill’s debate. The House Rules Committee has allotted debate time

to be controlled by the bill’s major sponsor and opponent. In the Senate, the leadership has

less control over floor debate. Once given the floor, a senator has unlimited time to speak.

Once a bill is debated on the floor of the House and the Senate, the leaders schedule it for a

vote on the floor of each chamber. By this time, the bill is expected to pass; otherwise, it is

not even brought to the floor.

1. Senators can use a tactic called filibuster to prevent action on legislation they oppose by

continuously holding the floor and speaking until the majority backs down. Once given

the floor, senators have unlimited time to speak, and it requires a vote of three-fifths of

the Senate to end a filibuster. This procedure is called cloture, a rule allowing a majority

of two thirds or three fifths of the members in a legislative body to set a limit on the

debate over a given bill.

2. Senators can also place “holds” or stalling devices, on bills to delay debate. The origin of

the hold is kept secret. Senators place holds on bills when they fear openly opposing

them will be unpopular.

C. Conference Committee: Reconciling House and Senate Versions of Legislation. The next

step is to send the bill to a conference committee to iron out the differences between the

versions issued by the different houses. Once the compromise bill version leaves

conference, the bill must pass another floor voting session in each chamber. Note for

students that it is easier for a bill to die than to emerge victorious from all the legislative

hurdles.

D. Presidential Action. Once a standard version of the bill has been adopted by both the

House and Senate, the final step for the bill is to go to the president, who may chose to do

the following:

1. Sign the bill: in this case, the bill becomes the law of the land.

2. Veto the bill: in this case, the president rejects the bill. The veto is the president’s

constitutional power to turn down congressional acts. A presidential veto may be

overridden by a two thirds vote of each congressional house.

3. Pocket veto the bill: this is a presidential veto that is automatically triggered if the

president does not act on a given piece of legislation passed during the final ten days of

a legislative session.

Point 4. How Congress Decides. External and internal factors play a role in congressional decision

making. External influences include the legislators’ constituencies, interest groups, and political parties.

Internal influences include party leadership, congressional colleges, and the president.

A. Constituency. The constituency influence is not straightforward. Most constituents do not

know what policies their representatives’ support. Still, in order to be re-elected, members of

Congress spend much time anticipating which policies constituents like.

B. Interest Groups. Interest Groups with the ability to mobilize followers can be very influential in

decision making. These groups lobby Congress by informing their membership by simulating

grassroots pressure (called astroturf lobbying, this technique can include mass mobilization via

collective mail) or by using congressional scorecards rating members’ voting decisions.

C. Party Discipline. Party leaders exert influence over party members’ congressional behavior.

This influence can take the following forms:

1. A party unit vote is a roll call vote in the House or in the Senate in which at least 50 percent

of the members of one party take a particular position and are opposed by at least 50

percent of the members of the other party. Party votes are rare today, although they were

common in the 19th century. A roll call vote is a vote in which each legislator’s yes or no

vote is recorded as the clerk calls the names of the members alphabetically. Congressional

party unity has increased in the last decade as the two major parties have taken deeply

divided positions on various issues such as abortion, the minimum wage, school vouchers,

affirmative action, and many others. Party unity is a product of shared ideology and

background plus party leadership and organization. Resources regularly used by party

leaders to secure party members’ voting support include the following: leadership PACs,

committee assignments, access to the floor, the whip system, logrolling, and the presidency.

2. Leadership PACs. The congressional leadership uses these independent fundraising

committees aggressively to win over a party’s congressional members. PACs enhance party

power and create a bond between the leaders and the members who receive their help.

3. Committee Assignments. By helping members get favorable committee assignments,

leaders create “debts” that members want to repay.

4. Access to the Floor. Floor time allocation is controlled by party leadership (the Speaker and

majority leaders recognize members to talk on the floor) in both the House and Senate.

5. The Whip System. The whip communication network takes polls of members to learn their

voting intentions. This enables leaders to know how support for a bill stands. This system

helps preserve party unity in both houses and allows leaders to be selective about when to

exert pressure on members.

6. Logrolling. The term refers to the legislative practice wherein agreements are made

between legislators in voting for or against a bill (“I’ll support you if you support me”).

7. The Presidency. The most influence is presidential. Support of the president is a criterion

for party loyalty, and party leaders are able to use it to rally some members.

D. Weighing Diverse Influences. Influence form external and internal factors vary in degree,

depending on the time or stage of the bill. Influence also varies according to the type of issue,

constituent interest, and the historical moment.

Point 5. Beyond Legislation: Other Congressional Powers. Legislation is not the only form of influence

Congress has in governing. Congress has other powers, including the Senate’s treaty and appointment

power and many others.

A. Oversight. Through hearings, investigations, and other techniques, Congress exercises control

over the activities of executive agencies. This means Congress supervises how legislation is

carried out by the executive branch. During hearings about appropriations (the amounts of

money approved by Congress in statutes {bills} that each unit or agency of government can

spend), most agencies are subject to oversight. Committees have the power to investigate and

bring criminal charges for contempt (failure to cooperate), for perjury(lying), and when fraud,

waste, and abuse are found.

B. Advise and Consent: Special Senate Powers. The Constitution grants the president the power

to make treaties and to appoint top executive and judicial offices only “with the advice and

consent of the Senate” (Article II, Section 2). For treaties, a two thirds consent in needed; for

appointments, a simple majority is required. This gives senators the power to set conditions and

is why presidents often resort to executive agreements (agreements made between the

president and other countries that have the force of a treaty but do not require the Senate’s

approval) instead of treaties.

C. Impeachment. The formal charge by the House of Representatives that a government official

has committed “treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” The Constitution

grants this power to the Congress. In the impeachment process, the House acts as a grand jury

by voting on whether to convict and forcibly remove the person from office, which requires a

two thirds Senate majority vote. This considerable power is an effective safeguard against the

executive tyranny that the Founders so feared.