travaini et al 1993_mammalia.doc

advertisement

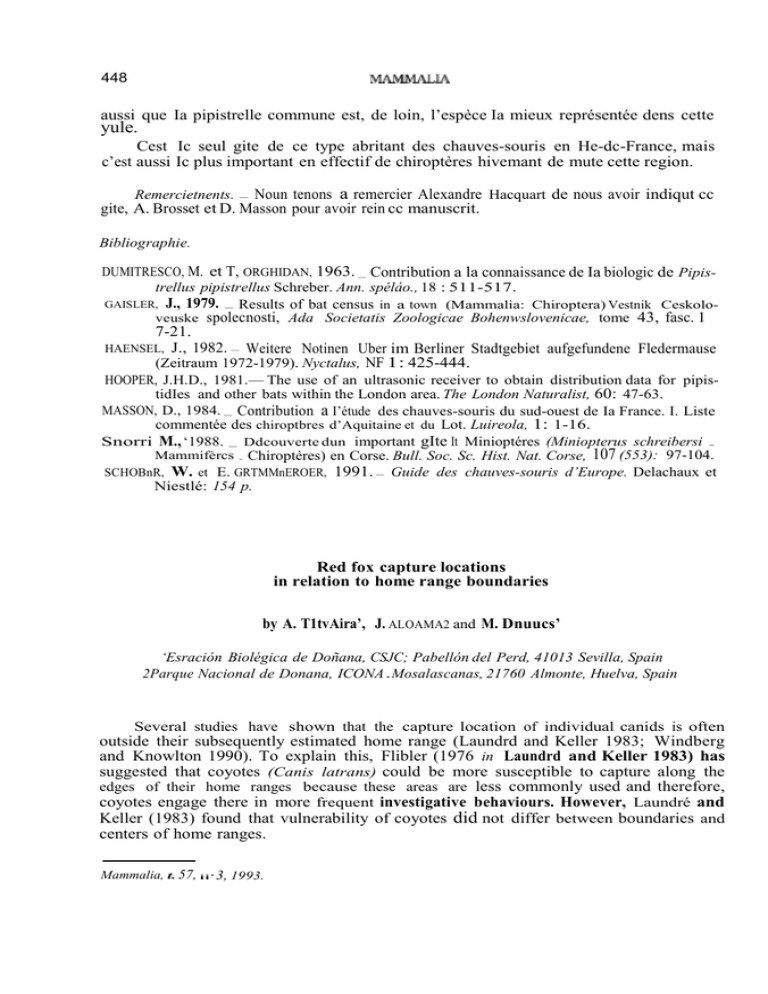

448 aussi que Ia pipistrelle commune est, de loin, l’espèce Ia mieux représentée dens cette yule. Cest Ic seul gite de ce type abritant des chauves-souris en He-dc-France, mais c’est aussi Ic plus important en effectif de chiroptères hivemant de mute cette region. Remercietnents. Noun tenons a remercier Alexandre Hacquart de nous avoir indiqut cc gite, A. Brosset et D. Masson pour avoir rein cc manuscrit. — Bibliographie. DUMITRESCO, M. et T, ORGHIDAN, 1963. Contribution a la connaissance de Ia biologic de Pipistrellus pipistrellus Schreber. Ann. spéláo., 18 : 511-517. GAISLER, J., 1979. Results of bat census in a town (Mammalia: Chiroptera) Vestnik Ceskoloveuske spolecnosti, Ada Societatis Zoologicae Bohenwslovenicae, tome 43, fasc. 1 — — 7-21. J., 1982. HAENSEL, — Weitere Notinen Uber im Berliner Stadtgebiet aufgefundene Fledermause (Zeitraum 1972-1979). Nyctalus, NF 1: 425-444. HOOPER, J.H.D., 1981.— The use of an ultrasonic receiver to obtain distribution data for pipistidIes and other bats within the London area. The London Naturalist, 60: 47-63. MASSON, D., 1984. Contribution a I’étude des chauves-souris du sud-ouest de Ia France. I. Liste commentée des chiroptbres d’Aquitaine et du Lot. Luireola, 1: 1-16. Snorri M., ‘1988. Ddcouverte dun important gIte It Minioptéres (Miniopterus schreibersi Mammifèrcs Chiroptères) en Corse. Bull. Soc. Sc. Hist. Nat. Corse, 107 (553): 97-104. SCHOBnR, W. et E. GRTMMnEROER, 1991. Guide des chauves-souris d’Europe. Delachaux et Niestlé: 154 p. — - — - — Red fox capture locations in relation to home range boundaries by A. T1tvAira’, J. ALOAMA2 and M. Dnuucs’ ‘Esración Biolégica de Doñana, CSJC; Pabellón del Perd, 41013 Sevilla, Spain 2Parque Nacional de Donana, ICONA Mosalascanas, 21760 Almonte, Huelva, Spain , Several studies have shown that the capture location of individual canids is often outside their subsequently estimated home range (Laundrd and Keller 1983; Windberg and Knowlton 1990). To explain this, Flibler (1976 in Laundrd and Keller 1983) has suggested that coyotes (Canis latrans) could be more susceptible to capture along the edges of their home ranges because these areas are less commonly used and therefore, coyotes engage there in more frequent investigative behaviours. However, Laundré and Keller (1983) found that vulnerability of coyotes did not differ between boundaries and centers of home ranges. Mammalia, t. 57, ii’ 3, 1993. NOTES 449 Here we present an analysis of the trappability and capture location of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in relation to their home range boundaries. Our purposes are a) determine if foxes are captured statistically more often inside or outside their subsequent home range limits, b) to evaluate the alternative explanation of a potential geographical shift of home range as a response to the stress of capture. Study area and methods. The study was carried out in the Biological Reserve of Dofiana, a 70 kin2 protected area inside the Doñana National Park, SW Spain (approximately 370 00’ N, 06° 30’ W). Data came from 10 foxes captured with padded steel traps and radiocollared (Wildlife Materials Inc., Carbondale, Illinois, U.S.A.) in 1985-1986 (1 adult female, 2 adult males and 1 subadult male) and February-June 1990 (6 aduii females, all of them pregnant or lactating when captured). They were located by triangulation using a portable receiver (A.V.M. Instrument Co., California, USA) and a hand-held Yagi antenna. Relocation data were computed and home ranges were calculated using the program McPAAL (Stuwe and Blohowiak 1985). Estimates of home range were determined using minimum convex polygons (Macdonald er a!. 1980), and harmonic mean transformations (Dixon and Chapman 1980) with 3 different contours (90%, 75 % and 50%). Capture sites that were not enclosed by contour of 90% will be considered as located at the edges or outside of the home range. As an index of trapping effort, we counted the number of nights each successful trap was active until it captured a fox. This information was available only for the six adult females captured in 1990. We cannot assume equal trapping effort through the home range of each individual fox. Results and discussion. Sex, location of the capture in relation to the subsequent home range, number of radiolocations, and areas included in the harmonic mean contours (90%, 75 % and 50%) of the 10 foxes are shown in table 1. For the six breeding females, which had a central place of activity (the den) and can be considered as typical resident individuals, we have tested if captures were made inside or outside the boundaries of the home range, as defined by the minimum convex polygon. Four of the six captures occurred outside (Table I), which rejects the assumption that capture location should be within the home range (p = 0.022, n =6, Binomial procedure; Siegel 1956). It could be that the increased energy requirements of the breeding females forced them to use the edges of their home range more often (M. Artois, comm. pers,). Nevertheless, the pattem of range frequentation by these females was a typical concentrical one, the frequency of radiolocations decreasing from the central den. From the ten trapped animals, seven (4 females and 3 males) were captured outside the 90% harmonic contour of their home range. Although this proportion is not statistically significant (p = 0.172, Binomial), it indicates a trend of the animals to be more trappable in the boundaries. We found no statistical differences between the sexes. Mean trapping effort for the six breeding females was 8.1 nights/trap, ranging from 1 to 18. There are no statistical differences in trapping effort between the foxes captured inside and in the edges of their home ranges (p = 0.267, n 6, Mann-Whitney U-test). 450 MAMMALIA TABLE 1. — Details of foxes trapped and tracked in Doflana National Park. Home range sizes are expressed in Ian2. Fox *; Sex Edge! Center Tracking Period (weeks) Radio— locations Mm. cony. Polygon aarmonic mean contour 50% 75% 90% I F C 36 215 11.290 2.748 4.593 6.375 2* F 5 9 58 2.715 0.300 0.686 2.178 3* F S 17 143 2.762 0.199 0.586 0.921 4* F 5 17 159 0.780 0.080 0.260 0.630 5* F C 7 50 2.369 0.627 1.180 P.232 6* F C 13 120 3.149 0.351 0.754 1.854 7* F 5 6 33 2.300 0.225 0.370 0.755 8 M S 9 50 2.129 0.400 1.180 2.500 9 bl 5 17 95 11.923 1.100 2.800 5.700 10 H E 3.1 72 12.580 1.900 4.800 7.930 Pregnant ox lactating females when captured. Our results confirm that most capt!Jres of red foxes occurred on the boundaries or outside the home range defined after the capture. This can be interpreted at least in two ways. Foxes could be more prone to be captured on the edges of their home ranges because these areas are less intensively used, and because of that, the animals show more investigative behaviour there (Laundrd and Keller 1983). It may, however, also be that animals suffering a stress as a result of the capture, change their habits, avoiding the trapping zone. In this case, the home range following the capture will be different from the home range before the capture. Trappability (here represented by trapping effort) was not higher on boundaries, as should be expected if the animals would be more prone to be captured there. A similar trend has been described by Laundrd and Keller (1983) for coyotes. Hence, the second explanation seems to be supported better by the data. We are aware more studies about trappability in carnivores should be made, specially on radiotagged animals monitored for long periods arid with at least one recapture. Also, studies in areas with different densities of the target animal are needed. In the same way as Windberg and Knowlton (1990), this study was carried out in a region with high density of foxes, estimated by Rau eta!. (1985) between 1 and 1.7 foxes/km2. If a significant geographical shift of the home range in red foxes occurs after being captured, as we have suggested, it should be considered in studies of spacing patterns and habitat use. Acicnow!edgements. This study was made possible by financial and logistical support train the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientIficas, the Insfituto Nacional para Ia Conservacidn de Ia Naturaleza and DOICYT PB 87-0405. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance in — NOTES 451 fox trapping and handling provided by Mr. R. Laffitte and P. Ferreras. Many helpful comments and important improvements on the manuscript were suggested by Dr. I. Mulder, Dr. 1. Goszczynski, Dr. J.-M. Weber, Dr. J.A. Litvaitis, Dr. F. Palomares, Dr. J.A. Donazar, Dr. M. Artois and an anonymous referee. N. Bustamante improved the English language. Bibliography. DixoN, RD. and J.A. CHAPMAN, 1980. Harmonic mean measure of animal activity areas. Ecology, 61: 1040-1044. HuRLER, S.J., 1976. Coyote movement patterns in Curlew Valley with emphasis on home range characteristics. M.S. Thesis. tJtth State Univ. Lngan. LAUNDRE, J.W. and B.L. KCLLaR, 1983. Trappability of coyotes relative to home range boundaries. Can. J. Zool., 61: 1932-1934. McooNALn, D.W., F.G. BAu. and NO. MOUGH, 1980.— The evolution of home range size and configuration using radio tracking data. Pp. 405424 in C.F. Amlaner, Jr., and D.W. Macdonald, eds. A handbook on biotelemetry and radto tracking. Pergamon Press. Oxford. UK. RAU, J.R., M. DELIBES, J. Ruiz and J.I. Sanvm4, 1985. Estimating the abundance of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in SW Spain. Pp. 869-876 in XVII Cong. mt. Union of Game Biol. Brussels. SIEGEL, S., 1956. Nonparametric methods for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill Book Co. New York. N.Y. Stowe, M. and C.E. BwRows.&tc, 1985. McPaal microcomputer programs for the analysis of animal locations (ver. 1.2). 19 pp. WINDBaG, L.A. and F.K. KNOWLTON, 1990. Relative vulnerability of coyotes to some capture procedures. Wildi. Soc. BulL, 18 : 282-290. — — — — — — Non aggressive encounter between a wolf pack and a wild boar by S. REtO Museo Naciona! de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, José (utiérrez Abascal 2, Madrid 28006, Spain Wild boar (Sus scrofa) is a common food for the wolf (Canis lupus) within the range where both species are sympatric (Rzebik-Kowalska 1972; Cuesta eta!. 1991); however, little is known about the wolf s hunting habits concerning this ungulate, especially regarding the relative dietary importance of killed versus scavenged prey. This note reports an encounter between a wolf pack and wild boars in which no attack by the wolves, and no attempt to escape by the boar, were seen. Though this record refers only to an isolated observation, it seems to suggest that boats can sometimes hold wolf packs at bay, in addition to using other tactics such as escape, group defense, etc. Thus, Mam,nalia, t. 57, n° 3,1993.